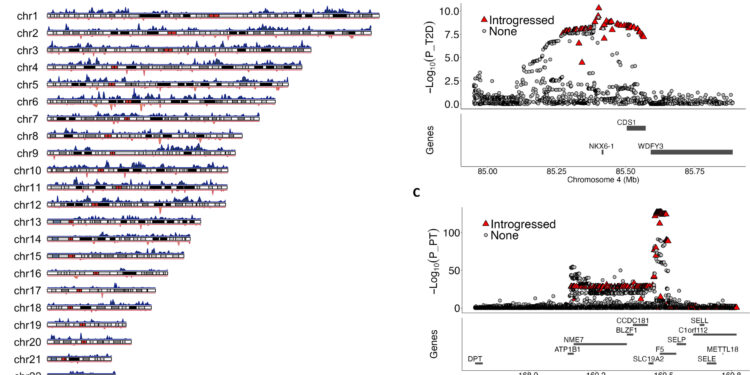

Introgressed sequences of archaic Neanderthals or Denisovans into the Japanese population. Credit: RIKEN

A genetic study conducted by researchers at RIKEN’s Center for Integrative Medical Sciences has revealed that Japanese people are descended from three ancestral groups.

The results, published in Scientific progress In April 2024, they challenge the long-held belief that there were two main ancestral groups in Japan: the indigenous Jomon hunter-gatherer-fishermen and the rice-farming migrants from East Asia.

Instead, the researchers identified a third group with potential links to Northeast Asia: the so-called Emishi people, lending further credence to a “tripartite origins” theory first suggested in 2021.

Japan’s population is not as genetically homogeneous as one might think, says RIKEN’s Chikashi Terao, who led the study. “Our analysis revealed the structure of Japan’s subpopulations at a very fine scale, which is very well classified according to the geographic locations of the country,” he says.

Looking for clues

Terao’s team reached their conclusions after sequencing the DNA of more than 3,200 people in seven regions of Japan, spanning the length of the country from Hokkaido in the north to Okinawa in the south. It is one of the largest genetic analyses of a non-European population to date.

The researchers used a technique called whole genome sequencing, which reveals an individual’s complete genetic makeup, all three billion base pairs of DNA. The method provides about 3,000 times more information than the more widely used DNA microarray method. “Whole genome sequencing gives us the ability to look at more data, which helps us find more interesting things,” Terao says.

To improve the usefulness of the data and examine potential links between genes and certain diseases, he and his collaborators combined the DNA information obtained with relevant clinical data, including disease diagnoses, test results, and medical and family history information. They compiled all of this into a database known as the Japanese Encyclopedia of Whole-Genome/Exome Sequencing Library (JEWEL).

One topic that particularly interested Terao was the study of rare genetic variants. “We felt that these rare variants could sometimes be traced back to specific ancestral populations and could be informative in revealing small-scale migration patterns within Japan,” he says.

Their intuition proved correct, helping to reveal the geographic distribution of Japanese ancestry. Jomon ancestry, for example, is most dominant on the subtropical coasts of southern Okinawa (present in 28.5% of samples) while it is weakest in the west (only 13.4% of samples).

In contrast, people in western Japan have a greater genetic affinity with Han Chinese, which Terao’s team believes is likely associated with the influx of migrants from East Asia between 250 and 794, and is also reflected in the historical full adoption of Chinese-style legislation, language, and education systems in that region.

Emishi ancestry, on the other hand, is more common in northeastern Japan, decreasing towards the west of the country.

Traces of the past

The researchers also examined JEWEL for genes inherited from Neanderthals and Denisovans, two groups of archaic humans who interbred with Homo sapiens. “We’re interested in why ancient genomes are integrated and preserved in modern human DNA sequences,” says Terao, who explains that these genes are sometimes associated with certain traits or conditions.

For example, other researchers have shown that Tibetans have Denisovan-derived DNA in a gene called EPAS1, which may have helped them colonize high-altitude environments. More recently, scientists have found that a Neanderthal-inherited gene cluster on chromosome 3—a trait found in about half of South Asians—is linked to a higher risk of respiratory failure and other severe COVID-19 symptoms.

Terao’s team’s analysis uncovered 44 ancient DNA regions present in modern-day Japanese, most of which are unique to East Asians. Among them was a Denisovan-derived DNA region in the NKX6-1 gene known to be associated with type 2 diabetes, which the researchers said could affect a person’s sensitivity to semaglutide, an oral drug used to treat the disease. They also identified 11 Neanderthal-derived segments linked to coronary heart disease, prostate cancer, rheumatoid arthritis and four other diseases.

Towards personalized medicine

The RIKEN-led team also used data on rare genetic variants to uncover potential causes of disease. For example, they found that a variant in a gene called PTPRD could be “extremely damaging” because it could be linked to high blood pressure, kidney failure, and heart attack, says Xiaoxi Liu, a senior scientist in Terao’s lab and first author of the study.

Additionally, the team noted a significant incidence of variants – also called loss-of-function variants – in the GJB2 and ABCC2 genes, which are associated with hearing loss and chronic liver disease, respectively.

Terao says untangling the relationship between genes, their variants and how these impact traits, including disease predisposition, could one day play a role in helping scientists develop personalized medicine.

“We tried to find and catalog loss-of-function genetic variants that are very specific to Japanese people, and understand why they are more likely to have certain specific traits and diseases,” he says. “We would like to link population differences to genetic differences.”

In the future, he hopes to expand JEWEL and include even more DNA samples in the dataset. For a long time, large-scale genomic studies have focused on analyzing data from people of European descent. But Terao believes that “it’s very important to extend this to the Asian population so that in the long run, the results can be useful to us as well.”

More information:

Xiaoxi Liu et al., Decoding triancestral origins, archaic introgression and natural selection in the Japanese population by whole genome sequencing, Scientific progress (2024). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adi8419

Quote: DNA study challenges thinking about people’s ancestry in Japan (2024, August 16) retrieved August 17, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.