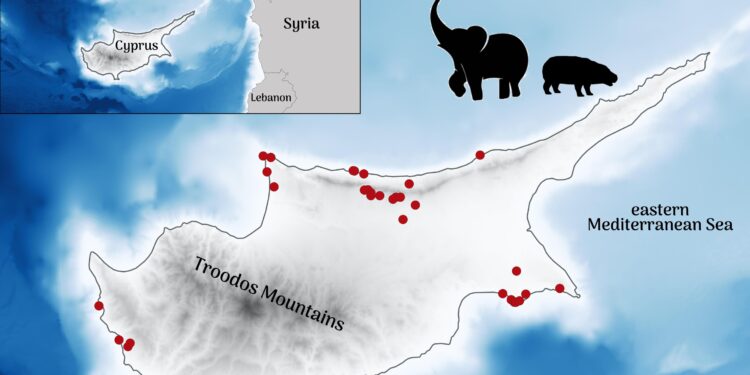

Map of Cyprus showing the approximate location of fossil sites where pygmy elephants and hippopotamuses have been found. Credit: Map created by CJA Bradshaw, Flinders University.

Scientists have solved the mystery of why hippos and pygmy elephants that once roamed the picturesque landscape of the Mediterranean island of Cyprus before the arrival of Paleolithic humans disappeared.

Cyprus had only two species of megafauna present during the Late Pleistocene: the 500 kg dwarf elephant (Palaeoloxodon cypriotes) and the 130 kg pygmy hippopotamus (Phanourios minor), but both species became extinct shortly after the arrival of humans around 14,000 years ago.

Looking at the reasons for the extinction of these prehistoric animals, researchers have found that Paleolithic hunter-gatherers in Cyprus may have driven first pygmy hippos, and then pygmy elephants, to extinction in less than 1,000 years.

The study, “Small populations of paleolithic humans in Cyprus hunted endemic megafauna to extinction,” by Corey Bradshaw, Frédérik Saltré, Stefani Crabtree, Christian Reepmeyer and Theodora Moutsiou, was published in the journal Nature. Proceedings of the Royal Society BIt was led by Professor Corey Bradshaw of Flinders University.

These results refute previous arguments that suggested that the introduction of a small human population to the island could not have caused these extinctions so quickly.

The researchers built mathematical models combining data from various disciplines, including paleontology and archaeology, to show that Paleolithic hunter-gatherers in Cyprus were most likely the main cause of the extinction of these species due to their hunting practices.

Skeleton of a pygmy hippopotamus (Phanourios minor) and an artist’s reconstruction of the animal on display at the Akamas Geological and Paleontological Information Centre in Pano Arodes, western Cyprus. Credit: CJA Bradshaw, Flinders University.

Professor Bradshaw, together with Drs Theodora Moutsiou, Christian Reepmeyer, Frédérik Saltré and Stefani Crabtree, used data-driven approaches to reveal the impact of rapid human colonisation on species extinction shortly after their arrival.

Using detailed reconstructions of human energy demand, diet composition, prey selection and hunting efficiency, the model demonstrates that the 3,000 to 7,000 hunter-gatherers predicted to be on the island were likely responsible for the extinction of both dwarf species.

“Our results therefore provide strong evidence that the Palaeolithic peoples of Cyprus were at least partially responsible for megafaunal extinctions during the Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene. The main determinant of extinction risk for both species was the proportion of edible meat they provided to the early inhabitants of the island,” said lead author Professor Corey Bradshaw of Flinders University.

-

Dwarf elephant (Palaeoloxodon cypriotes) remains including radius/ulna (1, 2), canines (3, 4), molars (5, 6, 7), rib fragment (14), metacarpus (15), humerus (17) and tibia (18) on display at the Akamas Geological and Palaeontological Information Centre at Pano Arodes, western Cyprus. Credit: CJA Bradshaw, Flinders University.

-

Heart of the Troodos Mountains, western Cyprus, showing the types of forests and terrain occupied by pygmy elephants and hippopotamuses in the Late Pleistocene. Credit: CJA Bradshaw, Flinders University.

-

Limestone caves like these are often where megafauna fossil remains are found. Credit: CJA Bradshaw, Flinders University.

“Our research lays the foundation for a better understanding of the impact that small human populations can have in terms of disruption to native ecosystems and major extinctions, even during a period of low technological capacity.”

The model’s predictions match the chronological sequence of megafauna extinctions in the paleontological record.

According to Dr Moutsiou, “Cyprus is the ideal place to test our models, as the island offers an ideal set of conditions to examine whether the arrival of human populations ultimately led to the extinction of its megafauna species. Indeed, Cyprus is an island environment and can offer a window into the past through our data.”

Previous findings by Professor Bradshaw, Dr Moutsiou and their colleagues have shown that large groups of hundreds to thousands of people could have arrived in Cyprus in two or three main migration events in less than 1,000 years.

More information:

Small populations of Paleolithic humans in Cyprus hunted the endemic megafauna to extinction, Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences (2024). DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2024.0967. royalsocietypublishing.org/doi….1098/rspb.2024.0967

Provided by Flinders University

Quote: Deciphering an ancient European extinction mystery: the disappearance of dwarf megafauna on Paleolithic Cyprus (2024, September 17) retrieved September 18, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.