Gravitational waves are ripples in the structure of space-time that travel at the speed of light. These are produced during some of the most violent events in the universe, such as black hole mergers, supernovae or the Big Bang itself. Since their first detection in 2015, and after three observation campaigns, the Advanced LIGO and Virgo detectors have detected around a hundred of these waves.

Thanks to these observations, we are beginning to reveal the population of black holes in our universe, to study gravity in its most extreme regime and even to determine the formation of elements like gold or platinum during the fusion of neutron stars.

The LIGO and Virgo detectors are nothing more than the most precise rulers ever built by humanity, capable of measuring the subtle compression and stretching of space-time produced by gravitational waves.

Detecting waves and determining their sources relies on comparing detector data with theoretical models, or “templates,” for the waves emitted by each type of source. This is essentially how the famous Shazam application gives us the details (name, author, year.) of the music played in a bar.

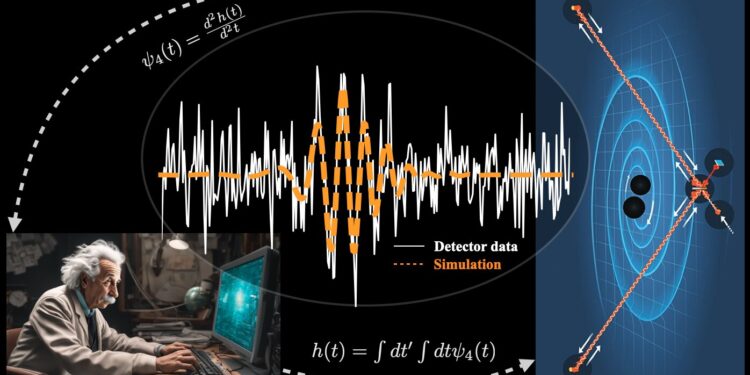

Although there are several ways to calculate gravitational wave models, the most accurate (and sometimes only) way is through extremely precise numerical simulations run on some of the world’s most powerful supercomputers. There is, however, a caveat: most numerical simulations do not generate the quantity read by the detectors, known as strain, but its second derivative, known as the Newman-Penrose scalar.

This requires scientists to perform double integrals on the results of their simulations. Dr Isaac Wong, co-leader of the study at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, explains: “Although taking integrals may seem simple, this operation is prone to well-known errors that we can only deal with for rather simple sources like fusion. black holes in circular orbits that LIGO and Virgo have detected so far. Additionally, it is not simple, requiring some manual tuning that involves human choices.

In recent work published in the journal Physical examinationa team led by Dr. Juan Calderón Bustillo “La Caixa Junior Leader” and “Marie Curie Fellow” from the Galician Institute of High Energy Physics (Spain) and Dr. Isaac Wong, from the Chinese University of Hong Kong, has proposed to reverse the way gravitational wave analyzes have been done since its birth.

Rather than taking integrals on their simulations, the authors propose taking derivatives on the detector data, while leaving their simulations intact.

Recreation of a boson star merger. Credit: Nicolas Sanchis Gual and Rocio Garcia Souto.

Dr. Calderón-Bustillo explains: “Although this modification may seem quite trivial, it has great advantages. First, it greatly simplifies the process of obtaining models that can be compared to LIGO-Virgo data. More importantly, we can now do this securely for any source that supercomputers can simulate. »

In fact, the team has long been interested in investigating the possibility that some of the current signals could be due to something much more exotic and mysterious, known as boson stars.

Dr Sanchis-Gual, co-author of the study from the University of Valencia, said: “Boson stars behave a lot like black holes, but they are fundamentally different, because they lack the two most important aspects. distinctive (and somewhat problematic) features of black holes. holes: their surface of no return known as the event horizon, and the singularity inside, where the laws of physics break down.

Even though the team knew how to simulate these sources in supercomputers, “we had a really hard time understanding how to turn the result of our simulations into something we could compare with the detector data, due to well-known problems.” the data made things extremely simple,” says Professor Alejandro Torres, also from the University of Valencia.

As the first application of their new technique, in a separate work published in Physical examination Dthe team compared some gravitational wave events observed by LIGO and Virgo to a large catalog of boson-star merger simulations.

“If there are boson star mergers, they could explain at least part of what we call dark matter,” explains Professor Carlos Herdeiro, from the University of Aveiro.

In fact, the team found that one of the most mysterious events observed to date, known as GW190521, is indeed consistent with such simulations. This reinforces a similar result the team achieved in 2020, achieved using a significantly smaller catalog.

Samson Leong, a doctoral student at the Chinese University of Hong Kong involved in both studies, said: “It is very exciting to see that GW190521 is consistent with a boson-star merger. This does not emphasize the potential role of these exotic objects in the future of gravitational wave astronomy.

Professor Tjonnie Li, from KU Leuven, adds: “This result also demonstrates the power of our new approach. By simply taking derivatives, we have opened a wider window to explore and understand the cosmos through gravitational waves. »

More information:

Juan Calderón Bustillo et al, Inference of gravitational wave parameters with the Newman-Penrose scalar, Physical examination (2023). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevX.13.041048

Juan Calderón Bustillo et al, Search for boson-star vector mergers within LIGO-Virgo intermediate-mass black hole merger candidates, Physical examination D (2023). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevD.108.123020

Provided by the Galician Institute of High Energy Physics

Quote: Scientists reverse analysis of gravitational wave data: Did LIGO and Virgo detect a merger of dark matter stars? (January 8, 2024) retrieved January 9, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.