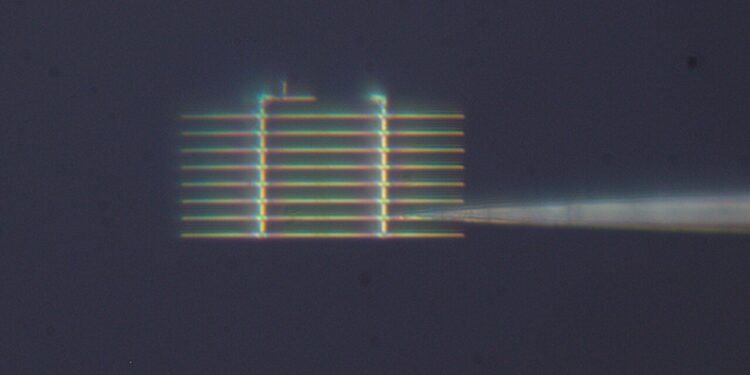

Microscope photograph of a device that could restart work towards the quantum Internet. The horizontal lines are diamond waveguides, each about 1,000 times smaller than a human hair. Credit: Atatüre Laboratory, University of Cambridge

In research that could jump-start work toward the quantum Internet, researchers at MIT and the University of Cambridge have built and tested an extremely small device that could enable the rapid and efficient flow of quantum information over large distances.

The key to the device is a “microchip” made of diamond in which some of the diamond’s carbon atoms are replaced with tin atoms. The team’s experiments indicate that the device, made of waveguides that allow light to carry quantum information, resolves a paradox that has blocked the arrival of large, scalable quantum networks.

Quantum information in the form of quantum bits, or qubits, is easily disrupted by ambient noise, such as magnetic fields, which destroy the information. On the one hand, it is desirable to have qubits that do not interact strongly with the environment. On the other hand, however, these qubits must interact strongly with light, or photons, essential for transporting information over long distances.

Researchers at MIT and Cambridge enable both by co-integrating two different types of qubits that work in tandem to store and transmit information. Additionally, the team reports great efficiency in transferring this information.

“This is a crucial step because it demonstrates the feasibility of integrating electronic and nuclear qubits in a microchip. This integration addresses the need to preserve quantum information over long distances while maintaining strong interaction with photons. This was made possible by combining the strengths of the University of Cambridge and MIT teams,” says Dirk Englund, associate professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS) at MIT and head of the MIT team. Englund is also affiliated with the MIT Materials Research Laboratory.

Professor Mete Atatüre, leader of the Cambridge team, said: “The results are the result of a strong collaborative effort between the two research teams over the years. It’s great to see the combination of theoretical prediction, device fabrication, and implementation of new quantum optical controls in one work. »

The work was published in Natural photonics.

Working at the quantum scale

A computer bit can be thought of as anything having two different physical states, such as “on” and “off”, to represent zero and one. In the strange, ultra-small world of quantum mechanics, a qubit “has the additional property that instead of being in just one of these two states, it can be in a superposition of both states. It can therefore be in these two states. at the same time,” explains Martínez. Multiple qubits entangled or correlated with each other can share much more information than the bits associated with conventional computing. Hence the potential power of quantum computers.

There are many types of qubits, but two common types are based on spin, or the rotation of an electron or nucleus (left to right or right to left). The new device involves both electronic and nuclear qubits.

A spinning electron, or electronic qubit, is very efficient at interacting with the environment, whereas the spinning nucleus of an atom, or nuclear qubit, is not. “We combined a qubit well known for easily interacting with light with a qubit well known for being very isolated, and therefore retaining information for a long time. By combining these two, we think we can get the best of both worlds “, says Martínez.

How it works? “The electron (electronic qubit) flowing through the diamond can get stuck at the tin defect,” says Harris. And this electronic qubit can then transfer its information to the rotating tin core, the nuclear qubit.

“The analogy I like to use is that of the solar system,” Harris continues. “You have the sun in the middle, it’s the tin core, then the Earth goes around it, and it’s the electron. We can choose to store the information in the direction of rotation of the Earth, it This is our electronic qubit. Or we can store information in the direction of the sun, which rotates around its own axis. This is the nuclear qubit.

Typically, light carries information via an optical fiber to the new device, which includes a stack of several tiny diamond waveguides, each about 1,000 times smaller than a human hair. Multiple devices could therefore serve as nodes controlling the flow of information in the quantum Internet.

The work described in Natural photonics involves experiments with a single device. “But eventually there could be hundreds, or even thousands, on a microchip,” Martínez says. In a 2020 study published in NatureMIT researchers, including several of the current authors, have described their vision for the architecture that will enable large-scale device integration.

Harris notes that his theoretical work predicted a strong interaction between the tin nucleus and the incoming electronic qubit. “It was ten times bigger than we expected, so I thought the calculation was probably wrong. Then the Cambridge team came and measured it, and it was interesting to see that the prediction was confirmed by experiment.”

Martínez agrees: “The theory and experiments finally convinced us that (these interactions) were actually happening. »

More information:

Ryan A. Parker et al, A diamond nanophotonic interface with an optically accessible deterministic electronuclear spin register, Natural photonics (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41566-023-01332-8

Provided by the Materials Research Laboratory at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Quote: The device could restart work towards the quantum Internet (February 1, 2024) retrieved February 1, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.