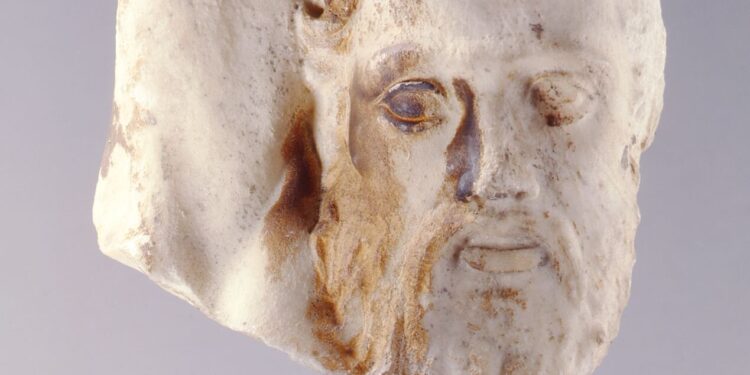

The analyzed centaur head from the Parthenon temple, National Museum of Denmark. Credit: John Lee, National Museum of Denmark

At the National Museum in Copenhagen, Denmark, there is a marble head that was once part of the ancient Greek temple of the Parthenon on the Acropolis of Athens. The head originally belonged to a centaur figure and was part of a scene depicting the battle of the Lapiths of Greek mythology against the centaurs (half-horse, half-human mythical creatures).

For reasons that remain to be explained, parts of the centaur’s head are covered with a thin brown film, as are several other marble fragments from the Parthenon. The mysterious brown film was first examined by the British Museum in 1830.

At the time, attempts were made to determine whether the color came from an ancient painting, but it was ultimately concluded that it could be the result of a chemical reaction between the marble and the air, or that the marble contained iron particles having migrated into the air. surface, coloring it brown.

Oxalic acid, algae and mushrooms

“There have been many attempts to explain this particular brown film. In 1851, the German chemist Justus von Liebig carried out the first real scientific investigation and determined that the brown film contained oxalates, salts of oxalic acid. This was confirmed by subsequent analyses, but the origin of the oxalates remained a mystery,” says Professor Emeritus Kaare Lund Rasmussen, expert in chemical analyzes of historical and archaeological objects at the Department of Physics, Chemistry and Pharmacy of the University of Southern Denmark.

Alongside colleagues Frank Kjeldsen and Vladimir Gorshkov from the University of Southern Denmark, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Bodil Bundgaard Rasmussen, former director of the antiquities collection at the National Museum of Denmark, Thomas Delbey from the Cranfield University in England, and Ilaria Bonaduce of the University of Pisa, Italy, published a scientific article describing the results of their research on the brown centaur head from the National Museum.

The article is published in Heritage Sciences.

“In particular, we wanted to examine whether the brown film could have been formed by a biological organism, such as a lichen, bacteria, algae or fungus. This theory had been suggested before, but no specific organism had been identified. The same goes for the “It could be remnants of paint applied, perhaps to protect or tone the marble surface,” explains Kaare Lund Rasmussen.

For their investigations, the research team was allowed to take five small samples from the back of the centaur’s head. These samples underwent various analyzes in SDU’s laboratories, including protein analysis and laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry.

“We found no traces of biological material in the brown layers, only from our own fingerprints and perhaps a bird’s egg that shattered on the marble in ancient times. This does not does not prove that there never was a biological substance, but it significantly reduces the probability, making the theory of a biological organism less likely today,” explains Kaare Lund Rasmussen.

Likewise, it is now less likely that the marble surface was painted or preserved, according to the researchers, who also looked specifically for traces of paint. Ancient paints were usually based on natural products such as eggs, milk and bones, and no traces of these ingredients were found in the brown stain alone.

The mystery remains

Through their investigations, the research team also discovered that the brown film is made up of two distinct layers. These two layers are approximately the same thickness, approximately 50 micrometers each, and differ in terms of trace element composition. However, both layers contain a mixture of oxalate, weddellite and whewellite minerals.

The fact that there are two distinct layers contradicts the theory that they were created by the migration of materials, such as iron particles, from inside the marble. This also contradicts the theory that they result from a reaction with air.

Air pollution is also unlikely for another reason: the centaur’s head was located inside Copenhagen long before the start of modern industrialization in the 18th century. In fact, this makes the heads from the National Museum particularly valuable compared to the marble pieces from the Acropolis, some of which were only brought inside recently.

“As there are two different brown layers with different chemical compositions, it is likely that they have different origins. This could suggest that someone applied paint or a conservation treatment, but as we have not found traces of such substances, the brown color remains a mystery”, concludes Kaare Lund Rasmussen.

How the Centaur’s Head Got to Denmark

The head of the centaur, along with another head from the Parthenon temple, arrived in Denmark in 1688 as a gift to King Christian V. It was brought by the Danish captain Moritz Hartmand, who served in the Venetian fleet and was present during the bombardment of the Acropolis of Athens in 1687. A significant part of the Parthenon temple was destroyed. The centaur’s head was placed in the Royal Kunstkammer, which later became the National Museum, where it has been on display ever since.

More information:

Kaare Lund Rasmussen et al, Analyzes of the brown spot on the head of the centaur from the Parthenon in Denmark, Heritage Sciences (2024). DOI: 10.1186/s40494-023-01126-9

Provided by the University of Southern Denmark

Quote: Despite intensive scientific analyses, this centaur head remains a mystery (January 18, 2024) retrieved January 19, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.