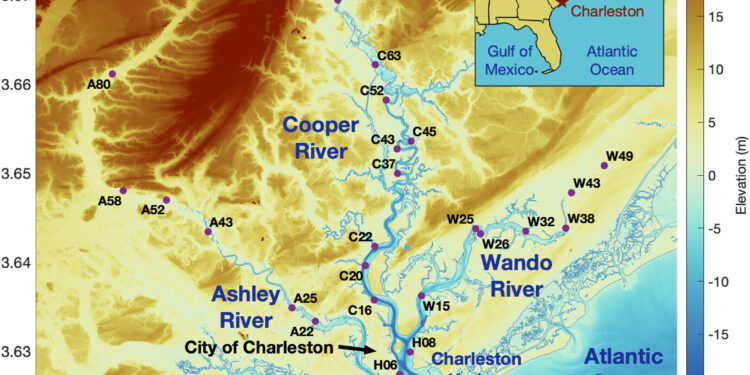

Map of the Charleston Harbor System, highlighting the location of water level measuring stations (purple dots). The axes are graduated in meters, UTM Zone 17. Credit: Geophysical Research Journal: Oceans (2024). DOI: 10.1029/2023JC020498

The common practice of building dams to prevent flooding may actually be contributing to worsening coastal flooding, a new study finds.

The study, published in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceansstudied the effects of dams built in coastal estuaries, where rivers and ocean tides interact. These large-scale infrastructure projects are gaining popularity globally, in part to help offset intensified storm surges, salt intrusion and sea-level rise fueled by climate change.

Analyzing data and measurements taken in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, more than a century ago, researchers determined that coastal dams do not necessarily mitigate flooding. Dams can either increase or decrease flood risk, depending on the duration of a surge and the friction caused by water flow.

“We generally think of storm surges as they get smaller as you go inland, but the shape of the basin can actually cause them to increase,” said lead author Steven Dykstra, an assistant professor in the College of Fisheries and Ocean Sciences at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

Estuaries are typically funnel-shaped, narrowing as they move inland. Damming shortens the estuary by providing an artificial wall that reflects storm waves moving inland. The narrowed channel shape also produces small reflections that change with the duration of the wave. Dykstra compared these storm-fueled waves to splashing in a bathtub, with certain wave frequencies causing water to splash over the sides.

After using Charleston Harbor as a case study, the researchers used computer modeling to assess flood response in 23 other estuaries in diverse geographic areas. These included both dammed and natural estuary systems, including Cook Inlet in Alaska.

The models confirmed that the shape of the basin and the changes that shorten it with a dam are the key to determining how storm surges and tides move inland. At the right amplitude and duration, waves in dammed environments increase rather than decrease.

The study also found that areas far from coastal dams could still be directly impacted by man-made infrastructure. In the Charleston area, the strongest storm surges regularly occurred more than 50 miles inland.

“The scary thing is that people don’t always realize they’re in a coastal zone of influence,” Dykstra said. “Sea level rise is making people inland aware that they’re not immune to the effects of coastal flooding, and that usually happens during massive floods.”

Other contributors to the study included Enrica Viparelli, Alexander Yankovsky and Raymond Torres of the University of South Carolina, and Stefan Talke of California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo.

More information:

Steven L. Dykstra et al., Storm surge and tidal reflection in dammed converging estuaries, the case of Charleston, USA, Journal of Geophysical Research: Oceans (2024). DOI: 10.1029/2023JC020498

Provided by University of Alaska Fairbanks

Quote:Dams built to prevent coastal flooding may make it worse (2024, September 12) retrieved September 12, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.