Credit: Cell (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.11.029

Alzheimer’s disease has struck a large Colombian family for generations, killing half of its members in the prime of life. But one member of this family escaped what seemed like fate: Although she inherited the genetic defect that caused her relatives to develop dementia in their 40s, she remained cognitively healthy into her 70s .

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis now think they know why. A previous study reported that unlike her relatives, the woman carried two copies of a rare variant of the APOE gene known as the Christchurch mutation.

In this study, researchers used genetically modified mice to show that the Christchurch mutation breaks the link between the early phase of Alzheimer’s disease, when a protein called beta-amyloid builds up in the brain, and the late phase, when another protein called tau accumulates and cognitive decline sets in. So the woman remained mentally alert for decades, even as her brain filled with huge amounts of amyloid. The results, published on December 11 in the journal Cellsuggest a new approach to prevent Alzheimer’s dementia.

“Any protective factor is very interesting, because it gives us new clues about how the disease works,” said lead author David M. Holtzman, MD, the Barbara Burton and Reuben M. Morriss III Distinguished Professor of Neurology.

“As people age, many begin to develop some accumulation of amyloid in their brain. Initially, they remain cognitively normal. However, after many years, amyloid deposition begins to lead to the accumulation of tau protein. When this happens, cognitive impairment quickly occurs. If we can find a way to mimic the effects of the APOE Christchurch mutation, we may be able to prevent people who are already on the path to Alzheimer’s dementia to continue on this path.

Alzheimer’s disease develops over a period of approximately 30 years. The first two decades or so were silent; Amyloid slowly accumulates in the brain without causing harmful effects. However, when amyloid levels reach a critical point, they trigger phase two, which involves multiple interrelated destructive processes: a protein called tau forms tangles that spread throughout the brain; brain metabolism slows down and the brain begins to shrink; and people begin to experience problems with memory and thinking. The disease follows the same pattern in people with genetic and non-genetic forms of Alzheimer’s.

Colombian families carry a mutation in a gene called presenilin-1 that causes far too much amyloid to build up in their brains starting in their 20s. People with the mutation accumulate amyloid so quickly that they reach the tipping point and begin to show signs of cognitive decline in middle age. A rare exception is a woman who had more amyloid in her brain at age 70 than her relatives in their 40s, but only very minimal signs of brain damage and cognitive impairment.

“One of the biggest unanswered questions in the field of Alzheimer’s disease is why amyloid accumulation leads to tau pathology,” Holtzman said. “This woman was very, very unusual in that she had amyloid pathology but not much tau pathology and only very mild late-onset cognitive symptoms. This suggested to us that she might hold clues to this link between amyloid and tau.”

A 2019 study found that in addition to a presenilin-1 mutation, the woman also carried the Christchurch mutation in both copies of her APOE gene, another gene associated with Alzheimer’s disease. But with only one person in the world known to have this particular combination of genetic mutations, there was not enough data to prove that the Christchurch mutation was responsible for his remarkable resistance to Alzheimer’s disease and that he did not It was not just a chance discovery.

To solve this conundrum, Holtzman and first author Yun Chen, a graduate student, turned to genetically modified mice. They took mice genetically predisposed to overproducing amyloid and modified them to carry the human APOE gene with the Christchurch mutation. Then they injected a tiny bit of human tau into the mouse brains. Normally, the introduction of tau into brains already filled with amyloid seeds is a pathological process in which tau collects into aggregates at the injection site, followed by the spread of these aggregates to other parts of the brain.

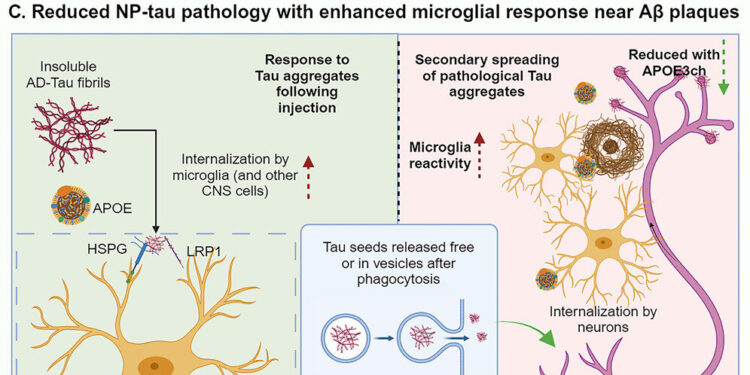

This was not the case in mice carrying the Christchurch mutation. Much like the Colombian woman, the mice developed minor tau pathology despite extensive amyloid plaques. The researchers found that the main difference was in the activity levels of microglia, the brain’s waste disposal cells. Microglia tend to cluster around amyloid plaques. In mice with the APOE Christchurch mutation, microglia surrounding amyloid plaques were revived and hyperefficient at consuming and clearing tau aggregates.

“These microglia take up Tau and degrade it before the Tau pathology can effectively spread to the next cell,” Holtzman said. “This blocked a lot of the downstream process; without tau pathology, you don’t get neurodegeneration, atrophy and cognitive problems. If we can mimic the effect of the mutation, we may be able to make the Amyloid accumulation is harmless, or at least much less harmful, and protects people from developing cognitive impairments.

More information:

Yun Chen et al, APOE3ch alters microglial response and suppresses Aβ-induced Tau seeding and spreading, Cell (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2023.11.029

Cell

Provided by the University of Washington School of Medicine

Quote: Clues to preventing Alzheimer’s disease come from a patient who escaped the disease, despite genetics (December 11, 2023) retrieved December 12, 2023 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.