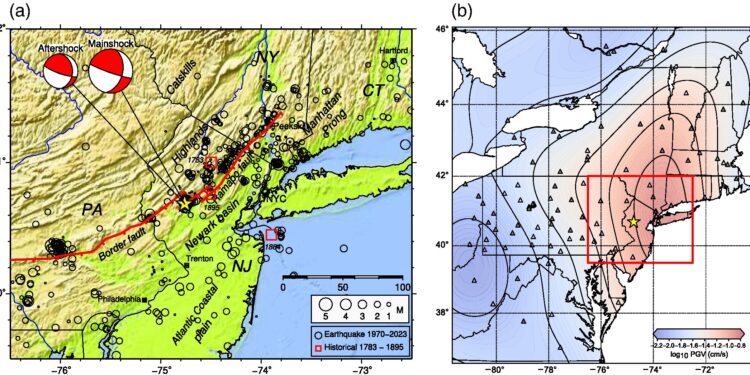

(a) Topographic map showing mainshock (yellow star) and seismicity (open circles) across geological units from west-northwest to east-southeast: Catskills, Highlands, Newark Basin and Atlantic coastal plain. (b) Contour map showing the maximum ground velocity (PGV) of the mainshock measured on transverse component recordings filtered at 0.3–10 Hz. Credit: The seismic file (2024). DOI: 10.1785/0320240020

The 4.8 magnitude Tewksbury earthquake surprised millions of people on the US East Coast, who felt the tremors caused by the largest instrumentally recorded earthquake in New Jersey since 1900.

But researchers noted something else unusual about the earthquake: why did so many people 40 miles away in New York City report strong shaking, while damage near epicenter of the earthquake seemed minimal?

In an article published in The seismic fileYoungHee Kim of Seoul National University and colleagues show how the earthquake’s rupture direction may have affected those who felt the strongest shaking on April 5.

Kim and his colleague and co-author Won-Young Kim of Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory became curious about the strange pattern of shaking after visiting the quake’s epicenter area eight hours only after the main shock.

“We expected some property damage – toppled chimneys, cracked walls or fallen plaster – but there were no obvious signs of property damage,” the researchers said in an email. “Police officers a few kilometers from the reported epicenter spoke calmly about the shaking caused by the main shock. It was a surprising response from residents and homes to a 4.8 magnitude earthquake in the area .”

“This contrasts with the broad and overwhelming response of residents in and around the New York region, approximately 40 miles from the epicenter,” they added.

The earthquake resulted in more than 180,000 felt reports – the largest number ever for a single earthquake received by the “Did You Feel It?” » from the US Geological Survey. app and website, according to a second article published in The seismic file by USGS seismologist Oliver Boyd and colleagues.

Boyd and his colleagues said the earthquake was felt by about 42 million people between Virginia and Maine.

Reports from people southwest of the epicenter, toward Washington, D.C., indicated shaking “weak” on the scale the USGS uses to measure the intensity of an earthquake, while people coming from the northeast of the epicenter felt “mild to moderate” shaking.

However, based on previous seismic magnitude and intensity models developed for the eastern United States, a magnitude 4.8 earthquake is expected to produce very strong shaking within a radius of about 10 kilometers or about six miles from its epicenter.

With this model in mind, Kim and his colleagues wanted to take a closer look at the directionality of the earthquake’s rupture. To model the rupture, they turned to a kind of seismic wave called Lg waves, due to the lack of nearby seismic observations at the time of the mainshock. Lg waves are shear waves that bounce in the crust between the Earth’s surface and the crust-mantle boundary.

The resulting model indicated that the seismic rupture propagated east-northeast and downward on an east-dipping fault plane. The direction of the rupture could have diverted the earthquake’s shaking from its epicenter toward the northeast, the researchers concluded.

Typically, earthquakes in the northeastern United States occur as thrust faults along north-south oriented faults. The New Jersey earthquake is unusual, Kim and colleagues noted, because it appears to have been a combination of a thrust and strike-slip mechanism along a possible north-northeast oriented fault plane.

“Earthquakes in eastern North America typically occur along the pre-existing zone of weakness, that is, existing faults,” the researchers explained. “In the Tewksbury area, a hidden fault plane oriented north-northeast and with a moderate dip can be mapped from the numerous small aftershocks detected and located” after the Tewksbury mainshock.

Boyd and his colleagues noted that some damage was documented by a reconnaissance team deployed by the Geotechnical Extreme Events Reconnaissance Association and the National Institute of Standards and Technology. Along with cracks in drywall and objects falling from shelves, the team documented the partial collapse of the stone facade of Taylor’s Mill, a pre-Revolutionary War structure near the town of Lebanon, N.S. Jersey.

Researchers have not yet attributed the quake to a particular fault, but the locations of the mainshock and aftershocks suggest that the region’s well-known Ramapo fault system was not active during the quake.

The findings could “help us identify new sources of earthquakes and rethink how stress and strain are managed in the eastern United States,” Boyd said.

He noted that some seismometers quickly deployed to the region by the USGS will remain in place for at least five months.

“This can help us study, for example, the mechanisms related to how the crust responds to the stress of a mainshock in the region, and how productive aftershock sequences can be in the eastern United States. United,” Boyd said.

“Good station coverage can also allow us to observe how seismic ground motions vary across the region based on magnitude, epicentral distance, and Earth structure. And each of these examples can help us to better appreciate the potential seismic risks.”

More information:

Sangwoo Han et al, Rupture model of the April 5, 2024 Tewksbury, New Jersey earthquake based on regional Lg-Wave data, The seismic file (2024). DOI: 10.1785/0320240020

Oliver S. Boyd et al, Preliminary Observations of the 4.8 Mw New Jersey Earthquake of April 5, 2024, The seismic file (2024). DOI: 10.1785/0320240024

Provided by the Seismological Society of America

Quote: Closer Look at New Jersey Earthquake Rupture May Explain Shaking Reports (October 2, 2024) Retrieved October 3, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.