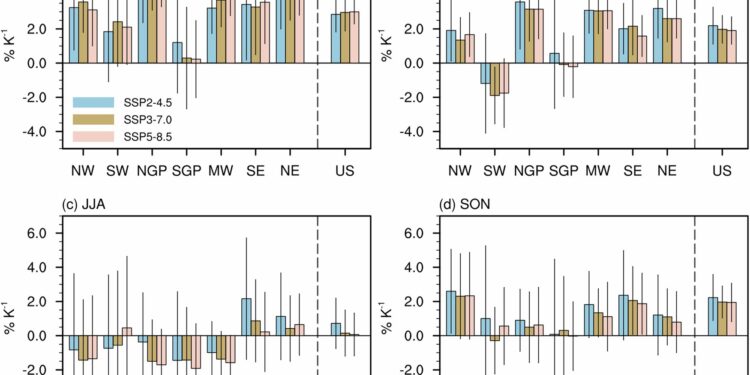

Projected subregional changes in seasonal precipitation, area-weighted (2070-2099 versus 1985-2014). Credit: npj Climate and atmospheric science (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41612-024-00761-8

Most Americans can expect wetter winters in the future due to global warming, according to a new study led by a University of Illinois at Chicago scientist.

Using climate models to study how winter precipitation in the United States will change by the end of the 21st century, a team led by Akintomide Akinsanola found that overall winter precipitation and extreme weather events will increase across most of the country.

The study in npj Climate and atmospheric science also reported an increased frequency of “very wet” winters, those that would rank in the top 5% of historical total winter precipitation in the United States. By the end of the 21st century, these previously rare winters would occur every four years in some parts of the country.

Combined with the shift from snow to rain in many parts of the country, these changes will have dramatic implications for agriculture, water resources, flooding and other climate-sensitive areas, said Akinsanola, an assistant professor of earth and environmental sciences at UIC.

“We found that, unlike summer and other seasons where projected changes in precipitation are very uncertain, there will be a strong future intensification of winter precipitation,” Akinsanola said. “It’s going to accelerate well beyond what we’ve seen in historical data.”

The team used 19 Earth System Models in their study and conducted their analysis across the seven U.S. subregions defined in the National Climate Assessment Report. The study compared projected precipitation for the end of the 21st century (2070-2099) to the current period (1985-2014).

Across the United States, they showed an increase in average winter precipitation of about 2 to 5 percent per degree of warming by the end of the 21st century. In terms of absolute change, the Northwest and Northeast of the United States saw the largest increases. Six of the seven regions will also experience more frequent very wet winters, with the largest increases seen in the Northeast and Midwest.

The southern Great Plains – the states along the southern border, such as Texas and Oklahoma – was the only region where the projected changes were very small and very uncertain. In this region, more frequent extreme dry events will offset or offset the increase in extreme wet events, Akinsanola said.

The results highlight that changes in winter precipitation will have a significant impact nationally and, in some regions, greater than predicted changes in spring and summer precipitation.

The composition of precipitation will also likely change in many areas. Previous studies predicted that as temperatures rise, more precipitation will fall as rain rather than snow, leading to a decrease in snow depth. This reduced snowpack and heavier rains will put a strain on existing systems.

“There will be a need to update or modernize infrastructure because we’re not just talking about average rainfall, we’re also talking about an increase in extreme events,” Akinsanola said. “Drainage systems and buildings will need to be improved to deal with potential flooding and storm damage.”

In his current and future work, Akinsanola will use higher-resolution models to predict changes in precipitation, heat waves, dry and hot extremes, and other extreme events at a more local level. He conducts some of his research in association with the Environmental Sciences Division of Argonne National Laboratory, where he holds a joint appointment.

More information:

Akintomide A. Akinsanola et al, Robust future intensification of winter precipitation in the United States, npj Climate and atmospheric science (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41612-024-00761-8

Provided by University of Illinois at Chicago

Quote: Climate change will lead to wetter winters in the United States, modeling study shows (September 26, 2024) retrieved September 26, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.