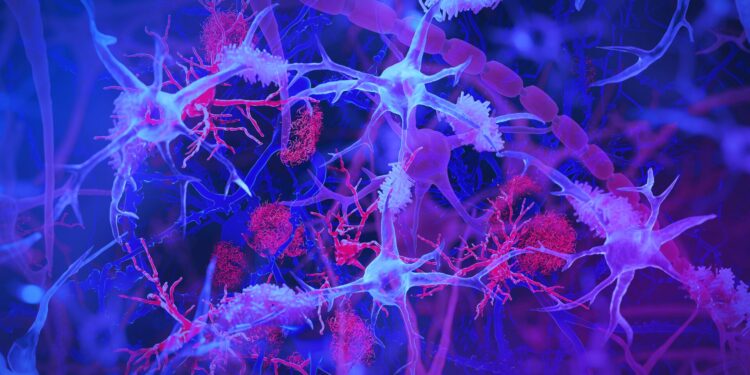

The brain’s immune cells, or microglia (light blue/purple), interact with amyloid plaques (red) – clumps of harmful proteins linked to Alzheimer’s disease. The illustration highlights the role of microglia in monitoring brain health and removing debris. Credit: Jason Drees/Arizona State University

Arizona State University and Banner Alzheimer’s Institute researchers and collaborators have discovered a surprising link between chronic intestinal infection caused by a common virus and the development of Alzheimer’s disease in a subset of people .

The results are published in Alzheimer’s and dementia.

Most humans are thought to be exposed to this virus, called cytomegalovirus or HCMV, during the first decades of life. Cytomegalovirus is one of nine herpes viruses, but it is not considered a sexually transmitted disease. The virus is usually transmitted through exposure to bodily fluids and only spreads when the virus is active.

According to the new research, in some people the virus may persist in an active state in the gut, where it can travel to the brain via the vagus nerve, a critical information highway that connects the gut and brain. . Once there, the virus can change the immune system and contribute to other changes associated with Alzheimer’s disease.

If the researchers’ hypotheses are confirmed, they may be able to evaluate whether existing antiviral drugs could treat or prevent this form of Alzheimer’s disease. They are currently developing a blood test to identify people who have active HCMV infection and who might benefit from antiviral treatment.

“We believe we have discovered a biologically unique subtype of Alzheimer’s disease that may affect 25 to 45 percent of people with this disease,” said Dr. Ben Readhead, co-first author of the study and associate professor research at ASU-Banner Neurodegenerative Disease Research. ASU Biodesign Institute Center.

“This subtype of Alzheimer’s disease includes amyloid plaques and tau tangles – microscopic brain abnormalities used for diagnosis – and has a distinct biological profile of viruses, antibodies and immune cells in the brain .”

Researchers from ASU, the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute, the Banner Sun Health Research Institute, and the Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen) led the collaborative effort, which included researchers from UMass Chan Medical School, Institute for Systems Biology, Rush University Medical Center and the Icahn School. of medicine at Mount Sinai and other institutions.

The research team suggests that some people exposed to HCMV develop a chronic intestinal infection. The virus then enters the bloodstream or travels through the vagus nerve to the brain. There, it is recognized by immune cells in the brain, called microglia, which activate the expression of a specific gene called CD83. The virus could contribute to the biological changes involved in the development of Alzheimer’s disease.

The role of brain immune cells

Microglia, or immune cells in the brain, are activated when they respond to infections. Although initially protective, a sustained increase in microglial activity can lead to chronic inflammation and neuronal damage, implicated in the progression of neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer’s disease.

In a study published earlier this year in Natural communicationsresearchers found that the postmortem brains of research participants with Alzheimer’s disease were more likely than those of people without Alzheimer’s disease to specifically harbor CD83(+) microglia.

Exploring why this happened, they discovered an antibody in the intestines of these subjects, consistent with the possibility that an infection could contribute to this form of Alzheimer’s.

In the most recent study, researchers sought to understand what might be causing intestinal antibody production. The team examined the spinal fluid of these same individuals, which revealed that the antibodies were specifically directed against HCMV. This prompted a search for evidence of HCMV infection in the gut and brain tissue of these subjects, which they found.

They also observed HCMV in the vagus nerve of the same subjects, raising the possibility that this is how the virus travels to the brain. In collaboration with RUSH University, researchers were able to replicate the association between cytomegalovirus infection and CD83(+) microglia in an independent cohort of Alzheimer’s disease patients.

To further study the impact of this virus, the research team then used human brain cell models to demonstrate the virus’s ability to induce molecular changes linked to this specific form of Alzheimer’s disease. Exposure to the virus actually increased the production of amyloid and phosphorylated tau proteins and contributed to neuron degeneration and death.

Is HCMV responsible for Alzheimer’s disease in some people?

HCMV can infect humans of any age. In most healthy individuals, infection occurs without symptoms but may present as a mild, flu-like illness. About 80% of people show signs of antibodies by the age of 80. Nonetheless, researchers have only detected intestinal HCMV in a subset of individuals, and this infection appears to be a relevant factor in the presence of the virus in the brain.

For this reason, the researchers note that simple contact with HCMV, which happens to almost everyone, should not be cause for concern.

And although researchers proposed more than 100 years ago that harmful viruses or microbes might contribute to Alzheimer’s disease, no single pathogen has been consistently linked to the disease.

The researchers suggest that these two studies illustrate the potential impact that infections can have on brain health and neurodegeneration in general. Still, they add that independent studies are needed to test their findings and resulting hypotheses.

Arizona’s unique biorepositories, particularly the Banner Sun Health Research Institute’s Brain and Body Donation Program, have provided tissue samples and resources including colon, vagus nerve, brain and cerebrovascular fluid. -spinal. The Religious Orders Study and the Memory and Aging Study led by Rush University provided additional brain samples and data. This allowed researchers to conduct a more nuanced investigation, highlighting the systemic rather than purely neurological roots of Alzheimer’s disease.

“It was extremely important for us to have access to different tissues from the same individuals. This allowed us to piece together the research. Arizona is the only place I know of where a study like this could have been done, and we are grateful to the Banner Health Brain and Body Donation Program for their support,” said Readhead, also the Edson Endowed Professor of Dementia Research at the center.

“We are extremely grateful to our research participants, colleagues and supporters who have given us the chance to advance this research in ways that none of us could have done alone,” said Dr. Dr. Eric Reiman, executive director of the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute and lead author of the study.

“We are excited to have the opportunity to allow researchers to test our results in ways that could make a difference in the study, subtyping, treatment and prevention of Alzheimer’s disease.”

The recent study results raise an important question: Could antiviral drugs help treat Alzheimer’s patients who have chronic HCMV infection?

Investigators are currently working on a blood test to identify individuals with this type of chronic HCMV intestinal infection. They hope to use it in conjunction with emerging Alzheimer’s disease blood tests to assess whether existing antiviral drugs could be used to treat or prevent this form of Alzheimer’s disease.

More information:

CD83(+) microglia associated with Alzheimer’s disease are linked to increased immunoglobulin G4 and human cytomegalovirus in the gut, vagal nerve and brain, Alzheimer’s and dementia (2024). DOI: 10.1002/alz.14401

Wang, Q., et al. Single-cell transcriptomes and multi-scale networks from people with and without Alzheimer’s disease. Natural communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-49790-0

Provided by Arizona State University

Quote: Chronic intestinal infection could play a role in the development of Alzheimer’s disease (December 19, 2024) retrieved December 19, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.