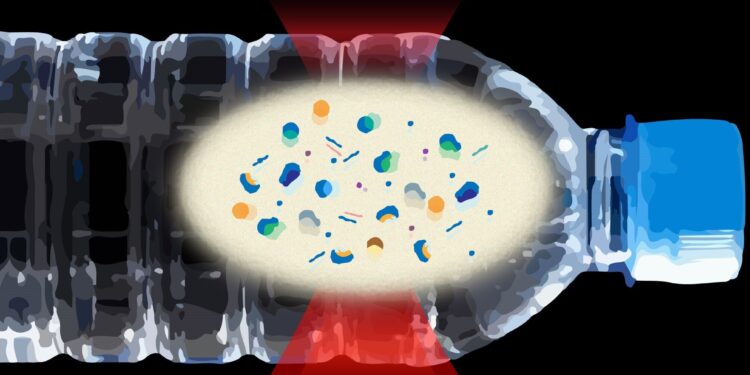

Using lasers, scientists photographed hundreds of thousands of previously invisible tiny plastic particles in bottled water. Credit: Naixin Qian, Columbia University

In recent years, there has been growing concern that tiny particles known as microplastics are appearing virtually everywhere on Earth, from polar ice and soil to drinking water and food. Formed when plastics break down into smaller and smaller pieces, these particles are consumed by humans and other creatures, with unknown potential effects on health and the ecosystem.

A major area of research: bottled water, which has been shown to contain tens of thousands of identifiable fragments in each container.

Now, thanks to newly perfected technology, researchers have entered a whole new plastic world: the little-known realm of nanoplastics, the offspring of microplastics that have degraded even further.

For the first time, they counted and identified these tiny particles in bottled water. They found that on average, one liter contained some 240,000 detectable plastic fragments, 10 to 100 times more than previous estimates, based mainly on larger sizes.

The study was published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Nanoplastics are so tiny that, unlike microplastics, they can pass through the intestines and lungs directly into the bloodstream and from there to organs, including the heart and brain. They can invade individual cells and cross the placenta into the bodies of unborn babies. Medical scientists are racing to study possible effects on a wide variety of biological systems.

“Before, it was just a dark, unexplored area. Toxicity studies were just guessing what was in there,” said Beizhan Yan, study co-author and environmental chemist at the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University. “It opens a window where we can look at a world that wasn’t exposed to us before.”

Global plastic production is approaching 400 million tonnes per year. More than 30 million tonnes are dumped into water or land each year, and many products made from plastic, including synthetic textiles, release particles during use.

Unlike natural organic matter, most plastics do not break down into relatively harmless substances; they simply divide and redivide into smaller and smaller particles of the same chemical composition. Beyond single molecules, there is no theoretical limit to their size.

A tiny particle of polystyrene plastic imaged by a new microscopic technique. Its diameter is approximately 200 nanometers, or 200 billionths of a meter. Credit: Naixin Qian, Columbia University

Microplastics are defined as fragments ranging from 5 millimeters (less than a quarter of an inch) to 1 micrometer, or 1 millionth of a meter, or 1/25,000th of an inch. (A human hair is about 70 micrometers in diameter.) Nanoplastics, which are particles smaller than 1 micrometer, are measured in billionths of a meter.

Plastics in bottled water became a public issue largely after a 2018 study detected an average of 325 particles per liter; later studies multiplied this number several times. Scientists suspected there were even more than they had so far counted, but good estimates stopped at sizes less than 1 micrometer, the limit of the nanoscale world.

“People developed methods to see nanoparticles, but they didn’t know what they were looking at,” said the new study’s lead author, Naixin Qian, a graduate student in chemistry at Columbia. She noted that previous studies could provide overall estimates of nanoscale mass, but for the most part they couldn’t count individual particles, or identify which ones were plastic or something else.

The new study uses a technique called stimulated Raman scattering microscopy, which was co-invented by study co-author Wei Min, a Columbia biophysicist. This involves probing samples with two simultaneous lasers tuned to resonate specific molecules. Targeting seven common plastics, the researchers created a data-driven algorithm to interpret the results. “It’s one thing to detect, but another to know what you’re detecting,” Min said.

The researchers tested three popular brands of bottled water sold in the United States (they declined to name which ones), analyzing plastic particles measuring down to just 100 nanometers.

They spotted between 110,000 and 370,000 particles in each liter, 90% of which were nanoplastics; the rest was microplastics. They also determined which of seven specific plastics it was and traced their shapes, qualities that could be useful in biomedical research.

One of the most common was polyethylene terephthalate, or PET. This wasn’t surprising, since that’s what many water bottles are made of. (It is also used for bottled sodas, sports drinks, and products such as ketchup and mayonnaise.) It likely enters the water in pieces that break off when the bottle is squeezed or exposed to heat. heat. A recent study suggests that many particles enter the water when you repeatedly open or close the cap, and tiny pieces get abraded.

Tiny pieces of polystyrene plastic, detected by lasers; each measures about 200 nanometers, or 200 billionths of a meter. Credit: Naixin Qian, Columbia University

However, PET was outnumbered by polyamide, a type of nylon. Ironically, Beizhan Yan said, it likely comes from plastic filters used supposedly to purify water before it is bottled. Other common plastics discovered by researchers: polystyrene, polyvinyl chloride and polymethyl methacrylate, all used in various industrial processes.

A somewhat worrying thought: The seven types of plastic the researchers looked for made up only about 10 percent of all nanoparticles found in the samples; they have no idea what the others are like. If it’s just nanoplastics, that means they could be in the tens of millions per liter.

But it could be almost anything, “indicating the complex composition of particles inside a seemingly simple water sample,” the authors write. “The common existence of natural organic matter certainly requires careful distinction.”

Researchers are now moving beyond bottled water. “There is a huge world of nanoplastics to study,” Min said. He noted that in terms of mass, nanoplastics are much less than microplastics, but “it’s not the size that matters. It’s the numbers, because the smaller things are, the more easily they can penetrate the earth.” ‘inside us’.

Among other things, the team plans to examine tap water, which also contains microplastics, although much less than bottled water.

Beizhan Yan is leading a project to study the microplastics and nanoplastics that end up in wastewater when people do laundry — by his calculations so far, millions per 10-pound load, from synthetic materials that make up many items. (He and his colleagues are designing filters to reduce pollution from commercial and residential washing machines.)

The team will soon identify particles in the snow that British collaborators trekking across West Antarctica are currently collecting. They are also collaborating with environmental health experts to measure nanoplastics in various human tissues and examine their developmental and neurological effects.

“It’s not totally unexpected to find so many things like this,” Qian said. “The idea is that the smaller things are, the more there are.”

The study was co-authored by Xin Gao and Xiaoqi Lang of Columbia’s Department of Chemistry; Huipeng Deng and Teodora Maria Bratu of Lamont-Doherty; Qixuan Chen of the Mailman School of Public Health in Columbia; and Phoebe Stapleton of Rutgers University.

More information:

Rapid chemical imaging of single nanoplastic particles by SRS microscopy, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2024). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2300582121. doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2300582121

Provided by Columbia Climate School

Quote: Bottled water may contain hundreds of thousands of previously uncounted tiny pieces of plastic, study finds (January 8, 2024) retrieved January 8, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.