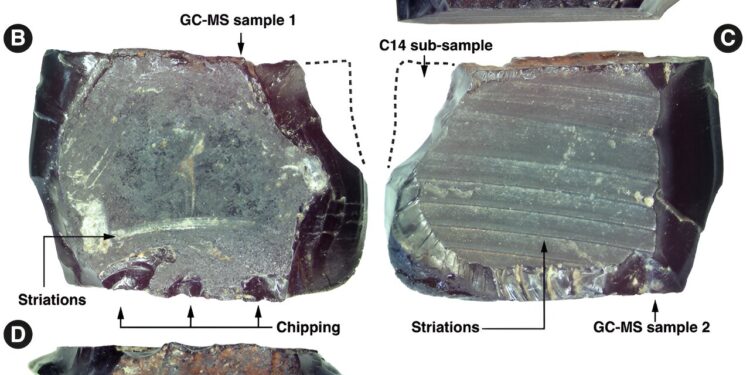

Image of the tree resin artifact from the lateral (A), dorsal (B), ventral (C) and other ventral side (D). Credit: Gaffney et al. 2024

The question of when and how humans dispersed across the Pacific remains a topic of intense debate. Previous studies have been hampered by imprecise chronometric dating, making it difficult to pinpoint the timing and movement of populations across the Pacific.

One of the earliest human-occupied sites in northern Australia is the Madjedbebe rock shelter, dated to about 65,000 to 60,000 years ago. To reach this area, Homo sapiens would have had to cross the Wallacea Islands to reach Sahul, the Pleistocene continent that connected New Guinea and Australia. However, sites along this southern route only show evidence of human occupation dating back about 44,000 years.

These discrepancies in the data have led some archaeologists to argue that the northern Australian dates are wrong and that humans probably did not arrive at Sahul until much later, after 50 ka.

A recent publication by archaeologist Dr Dylan Gaffney and a team of international researchers, published in Antiquityprovided the earliest known evidence of humans arriving in the Pacific more than 50,000 years ago.

The discovery, in the form of a tree resin artefact from Mololo Cave on Waigeo Island, dates back to around 55,000-50,000 years ago. Made by cutting down a tree and extracting the hardened sap, it offers insight into when and how Homo sapiens may have migrated across these islands, the routes they took and how they adapted to the new challenges and opportunities around them.

The method of extraction is similar to that used in ethnographic accounts to describe how the Waigeo people extracted tree resin. It is not known what the resin was used for. However, tree resin is multifunctional and could have been used to fuel fires, build boats, or for hafting stone tools.

According to Dr. Gaffney, “The Molokai resin provides evidence of sophisticated technological processes developed by people who settled in rainforest environments (where resin trees are found). This helps us understand the adaptability and flexibility of early human gathering groups in the Pleistocene.”

Homo sapiens probably reached the island by boat, around 50,000, when the distance between Waitata and Sahul was, on average, 5–6 km or only 2.5 km wide at its narrowest point.

Dr Gaffney explains that these results were obtained using navigation models. “We used computer simulations of Pleistocene ocean currents to model the time it would have taken to cross these islands. We found that sailors wishing to cross these inlets would have had a high success rate and that experienced sailors could have done so relatively easily.”

In addition to the tree resin artifacts, other artifacts provide insight into the strategies and adaptive abilities of these early humans. The fauna accumulated in the cave is a mixture of natural and human-accumulated remains, indicating that humans were skilled hunters capable of exploiting the fauna of these forested tropical environments.

“Some of the bones in the deposit are likely to be natural, including those of small animals such as small rodents and microbats. Other larger animals such as land birds, marsupials and megabats are more likely to be the result of human predation,” Dr Gaffney said.

In addition, marine remains, including teeth of fast-swimming carnivorous fish and sea urchins, were found. These were believed to have been taken from the coast, about 15 km away, and brought to the cave for further processing.

These results contribute to the current understanding of the breadth of the human diet and show that humans traveling along the northern route did not limit their diet to marine resources, contrary to what has been argued for the southern route.

In addition, lithic artefacts have been recovered from Mololo, although apart from a potential core, none date to the Late Pleistocene, around the time the tree resin artefact was discovered. The rarity of lithic artefacts is characteristic of sites in northeastern Wallacea and northwestern New Guinea, where many tools would have been made from organic materials.

Although rare, the excavations at Mololo Cave provide crucial information about occupation along the northern route to Sahul. The Mololo assemblage was most likely made by Homo sapiens. However, it is possible, based on modern population genetics, that individuals with Denisovan and Homo sapiens ancestry may have been the ones migrating along this northern route.

Further research will need to be conducted to obtain a clear picture of the movement and timing of these human populations, and not just in Mololo.

“We are already undertaking further research in the Raja Ampat Islands,” Dr Gaffney said. “Despite the challenges of working in these rainforest environments, there is considerable potential to greatly improve our understanding of the human past here,” he added.

More information:

Dylan Gaffney et al., Human Dispersal and Plant Transformation in the Pacific 55,000–50,000 Years Ago, Antiquity (2024). DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2024.83

© 2024 Science X Network

Quote:Ancient tree resin artifacts provide earliest known evidence of human dispersal across the Pacific (2024, August 20) retrieved August 20, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.