Task 2AFC. Credit: Natural neuroscience (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41593-024-01767-4

Just as a musician can train himself to more accurately distinguish subtle differences in pitch, mammals can improve their ability to interpret hearing, vision, and other senses with practice. This process, called perceptual learning, can be enhanced by activating a major nerve that connects the brain to almost every organ in the body, a new study in mice shows.

Led by researchers at NYU Langone Health, the investigation focuses on the vagus nerve, which carries signals between the brain and the heart, digestive system and other organs. Experts have long explored targeting this nerve with mild electrical pulses to treat a wide variety of conditions ranging from epilepsy and depression to post-traumatic stress disorder and hearing problems. The results of these efforts, however, have been mixed, and the underlying mechanisms that might lead to hearing improvement have until now remained unclear.

The article is published in the journal Natural neuroscience.

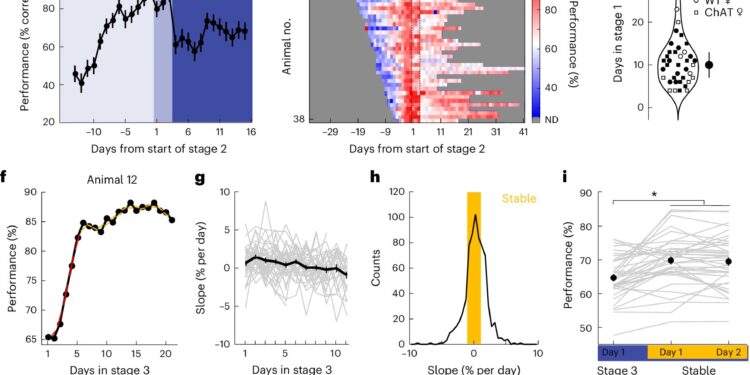

To take a closer look at whether vagus nerve stimulation can boost perceptual learning, the study team trained 38 mice to distinguish musical tones. Initially, performance improved for all animals, which made fewer and fewer errors over time.

However, while those without treatment peaked after about a week of training, the rodents given nerve stimulation continued to improve at their task, making on average about 10% fewer errors for the most part. tests than before the simulation. Additionally, mice in this group made half as many errors as their counterparts during the most difficult assessments, in which they had to distinguish very similar tones.

“Our results suggest that activating the vagus nerve during training may push the limits of what animals, and perhaps even humans, can learn to perceive,” said the study’s lead author, Kathleen Martin, BS, graduate student at NYU Grossman Neuroscience Institute. School of Medicine.

In a second part of the investigation, the researchers assessed how and where vagus nerve stimulation affects the brain. The results revealed that the technique stimulates cholinergic basal forebrain activity, a region involved in attention and memory. When the team removed this area during nerve activation, the rodents did not experience additional learning benefits.

Additionally, the team showed that stimulating the vagus nerve increased neuroplasticity, a process by which brain cells become more capable of adapting to new experiences and forming memories, in the auditory cortex, the main center hearing of the brain. This can lead to long-term cellular changes that allow new skills to persist long after training, Martin says.

She notes that targeting the vagus nerve to improve hearing has already been controversial among experts, with previous animal studies failing to show significant improvements.

The new study, published online September 16, suggests that the method may indeed work, although the results took longer to appear than the researchers initially expected, the authors say. This delay, Martin adds, could be due in part to the fact that the electrical pulses used in the technique can distract the animals being tested, who may need time to adjust to the sensation.

The authors note that using vagus nerve stimulation to improve hearing has potential applications far beyond maximizing musical abilities. Perceptual learning is a key component of both understanding a new language and adapting to cochlear implants, neuroprosthetic tools used to restore hearing loss. Notably, patients often take months to adapt to these devices, and many continue to have difficulty chatting even after years of use.

“These results highlight the potential for vagus nerve stimulation to accelerate hearing improvements with cochlear implants,” said lead study author Robert Froemke, Ph.D. “By stimulating perceptual learning , this method could allow implant recipients to communicate more easily with others, hear approaching cars, and engage more effectively with the world around them.”

Froemke, the Skirball professor of genetics in the department of neuroscience and physiology at NYU Grossman School of Medicine, says that electrical stimulation devices currently used to activate the vagus nerve are only a few centimeters in diameter and can be implanted as outpatient surgery. procedure. Some devices, such as those used to relieve migraines, are even less invasive and are simply held against the skin of the neck.

Based on their findings, the researchers next plan to test vagus nerve stimulation in rodents with cochlear implants to see if it improves their function, says Froemke, also a professor in the Department of Otolaryngology and Medicine. head and neck surgery at NYU Grossman School of Medicine.

Also a member of NYU Langone’s Neuroscience Institute, Froemke cautions that because the vagus nerve is much larger and more complex in humans than in mice, the effects of stimulating it may differ and therefore warrant further testing in human patients.

More information:

Kathleen A. Martin et al, Vagus nerve stimulation recruits the central cholinergic system to enhance perceptual learning, Natural neuroscience (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41593-024-01767-4

Provided by NYU Langone Health

Quote: Adding vagus nerve stimulation to training sessions can improve the quality of sound perception (October 9, 2024) retrieved October 9, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.