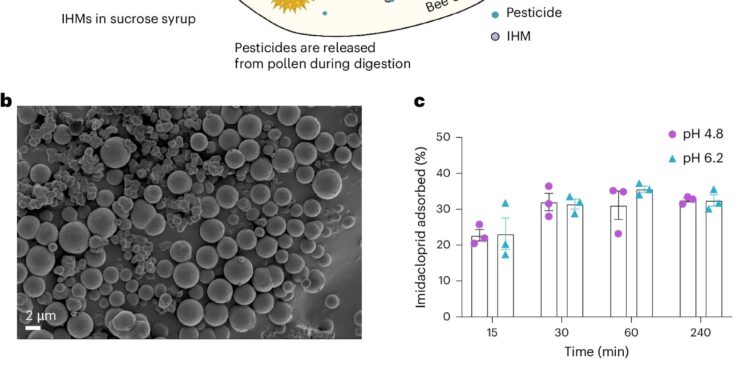

Schematic of pesticide detoxification strategy using HMI and HMI characterization. Credit: Nature and sustainability (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41893-024-01432-5

Scientists may have found an antidote to pesticides that directly and indirectly kill bees, according to a new paper published in Nature and sustainability showing promising preliminary results in eastern common bumblebees.

These findings are critically important because bees provide essential pollination services for nearly 80% of the world’s crops, yet annual losses of managed honeybee hives in the United States averaged 44% between 2017 and 2020. Dozens of studies have documented regional and global declines in wild bees, the paper said.

The proof-of-concept study in bumblebees describes the use of tiny, ingestible hydrogel microparticles—5 microns in diameter and visible only under a microscope—that physically bind to neonicotinoids, a class of pesticides banned in Europe and still used to limited extents in the United States. Once absorbed, the pesticides and microparticles pass through the bee’s digestive tract and are excreted.

The study found that when the microparticles were administered to bumblebees in sugar water, they resulted in 30% higher survival rates in bumblebees exposed to lethal doses of neonicotinoids, and significantly reduced symptoms in bumblebees exposed to sublethal doses of the chemical.

The antidote has the potential to be applied selectively to other pesticides, including widely used organophosphates.

“Bees are essential for crop pollination and agriculture, as well as food security, so it’s important that people take bee health seriously,” said Julia Caserto, Ph.D. ’24, first author of the paper and a former member of the lab of Minglin Ma, professor of biological and environmental engineering in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and corresponding author of the paper.

Eliminating pesticides altogether would be a good goal, but it may not be entirely realistic, Caserto said. “We want to try to overcome these pesticide exposures in honeybees so that we can still have enough crop pollination so that we’re all sustainable.”

Neonicotinoids enter groundwater and can be taken up by plants, entering pollen and nectar. When bees collect nectar, they can be exposed to the pesticide, which specifically targets the insects’ receptors. Bees also bring contaminated pollen back to hives.

At sublethal doses, neonicotinoids affect bees’ mitochondria, the cellular organelle where energy is produced, and they can affect energy transfer in bees, inhibiting movement and flight. They also compromise bees’ immunity, making them more vulnerable to mites and viruses.

The study showed that when bumblebees were given lethal doses of neonicotinoids, bees fed microparticles had a 30% higher survival rate than bees that did not receive the antidote. The researchers also found that after a sublethal dose, microparticle treatment improved the bees’ motivation to forage and led to a 44% increase in the number of bees able to cross the experimental channels. Similarly, using a high-speed camera, the researchers found that the wingbeat frequency altered after exposure improved significantly with treatment.

Future research directions could include testing the remedy on managed honeybees, which are smaller than bumblebees, so the pesticides might have different effects.

The treatment is not feasible for wild bees because it would be difficult to administer the microparticles. If the antidote is eventually applied to honeybees in the field, the microparticles could be added to already-used supplements, such as pollen cakes, which contain pollen and other nutrients.

“The research not only provides a potential strategy to address pesticide-related issues for honeybees, but also an example where interdisciplinary approaches – such as biomaterials in this case – can be adopted to address agricultural and sustainability challenges,” Ma said.

More information:

Julia S. Caserto et al, Ingestible hydrogel microparticles improve honeybee health after pesticide exposure, Nature and sustainability (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41893-024-01432-5

Provided by Cornell University

Quote: Antidote to pesticides deadly to bees shows promise (September 11, 2024) retrieved September 11, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.