Infection of alveolar macrophages is the first stage of tuberculosis. What if we could change that? Credit: Alissa Rothchild

Tuberculosis, caused by the bacteria Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), kills more than 1.6 million people a year, making it one of the leading causes of death from infectious agents worldwide – and that number is only ‘increase.

It’s not yet clear how exactly ATV evades the immune system, but a collaborative team of researchers from the University of Massachusetts Amherst and the Seattle Children’s Research Institute recently discovered something surprising: prior exposure to a genus of bacteria called Mycobacterium appears to remodel the immune system. frontline defenders of the body’s immune system.

Additionally, how these cells are remodeled depends on exactly how the body is exposed. These results, published in PLOS Pathogenssuggest that a more integrated therapeutic approach targeting all aspects of the immune response could be a more effective strategy in the fight against tuberculosis.

“We breathe thousands of liters of air every day,” says Alissa Rothchild, assistant professor in the department of veterinary and animal sciences at UMass Amherst and lead author of the paper. “This essential process makes us incredibly vulnerable to inhaling all sorts of potentially infectious pathogens that our immune systems must respond to.”

Systems, plural. When we think of immunity, we usually think of the adaptive immune system, which is when prior exposure to a pathogen – for example a weakened version of chicken pox – teaches the immune system what to protect against . Vaccination is the most commonly used tool to teach our adaptive immune system what to watch out for.

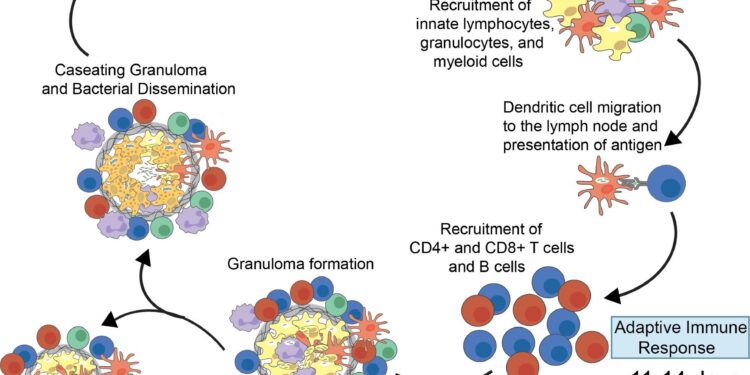

Although the adaptive immune system is the primary focus of most vaccine research (think protective antibodies induced by COVID-19 vaccines), it is not the body’s first responder: that would be the innate immune system and its ranks of macrophages. Macrophages are the frontline defenders of tissues that recognize and destroy pathogens and also require reinforcement. They achieve this in particular by activating different inflammatory programs which can modify the tissue environment.

In the case of the lungs, these macrophages are called alveolar macrophages (AM). They live in the alveoli of the lungs, the tiny air sacs where oxygen passes into the bloodstream, but, as Rothchild showed in a previous paper, AMs do not mount a robust immune response when initially infected by Mtb.

This lack of response seems to be a chink in the body’s armor that VTT exploits so devastatingly. “Mtb takes advantage of the immune response,” says Rothchild, “and when they infect an AM, they can replicate there for a week or more. They effectively turn the AM into a Trojan horse in which bacteria can hide the body’s defenses.

“But what if we could change this first step in the infection chain?” Rothchild continues. “What if AMs responded more effectively to Mtb? How could we modify the body’s innate immune response? Studies over the past decade have demonstrated that the innate immune system is capable of undergoing long-term changes, but we are just getting started. to understand the underlying mechanisms behind them.

Alveolar macrophages infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis on day 10 after infection. Mountain biking in green. Credit: Greg Olson

To test the conditions under which the innate immune response might be reshaped, Dat Mai, a research associate at Seattle Children’s Research Institute and first author of the paper, Rothchild and colleagues designed an experiment using two different mouse models.

The first model used the BCG vaccine, one of the most widely distributed vaccines in the world and the only vaccine used against tuberculosis. In the second model, the researchers induced contained Mtb infection, which they had previously shown protected against subsequent infections as a form of concurrent immunity.

A few weeks after exposure, the researchers challenged the mice with aerosolized Mtb, and infected macrophages were collected from each mouse model for RNA sequencing. There were striking differences in the RNA of each set of models.

While both sets of AMs showed a stronger pro-inflammatory response to Mtb than AMs from unexposed mice, BCG-vaccinated AMs strongly activated a type of inflammatory program, driven by interferons, while AMs from contained Mtb infection activated a response qualitatively. different inflammatory program.

Further experiments showed that different exposure scenarios changed the AMs themselves and that some of these changes appeared to depend on the broader lung environment.

“What this tells us,” says Rothchild, “is that there is a lot of plasticity in the macrophage response and that it is possible to therapeutically exploit this plasticity so that we can reshape the innate immune system to fight against tuberculosis.

This research is part of a much larger, cross-species, global effort to comprehensively understand immune responses to eliminate TB, called IMPAc-TB, for immune mechanisms protecting against Mycobacterium Tuberculosis.

Dr. Kevin Urdahl, professor of pediatrics at Seattle Children’s Research Institute, principal investigator of this IMPAc-TB consortium and one of the co-authors of the article, says that “the overall goal of the program is to elucidate how the immune system effectively controls or eradicates the bacteria that causes tuberculosis so that effective vaccines can be developed.

“This is an important part of the larger IMPAc-TB program, as we will assess the responses of human alveolar macrophages recovered from individuals who have recently been exposed to Mycobacterium tuberculosis in a tuberculosis endemic region. The findings of Rothchild’s team will help us interpret and understand the results we obtain from human cells.

More information:

Mycobacterium exposure remodels alveolar macrophages and the early innate response to Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, PLoS Pathogens (2024). DOI: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1011871. journals.plos.org/plospathogen… journal.ppat.1011871

Provided by University of Massachusetts Amherst

Quote:TB: How prior exposure to bacteria changes the lungs’ innate immune response and what this could mean for vaccines (January 18, 2024) retrieved January 18, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.