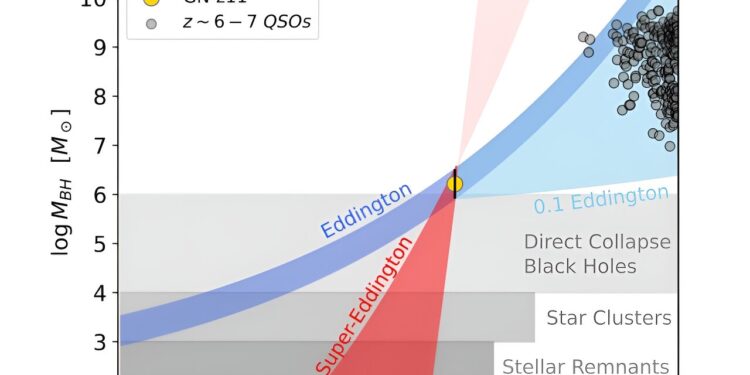

Black hole mass as a function of redshift (on a logarithmic scale) and age of the Universe. The black hole mass inferred for GN-z11 is represented by the large gold symbol. Credit: arXiv (2023). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2305.12492

Researchers have discovered the oldest black hole ever observed, dating back to the dawn of the universe, and found that it is “eating” its host galaxy to death.

The international team, led by the University of Cambridge, used the NASA/ESA/CSA James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to detect the black hole, which dates back 400 million years after the Big Bang, more than 13 billion years. The results, which lead author Professor Roberto Maiolino says constitute “a giant step forward”, are published in the journal Nature.

The fact that this surprisingly massive black hole – a few million times the mass of our sun – exists even this early in the universe calls into question our assumptions about the formation and growth of black holes. Astronomers believe that supermassive black holes found at the centers of galaxies like the Milky Way grew to their current sizes over billions of years. But the size of this newly discovered black hole suggests they could form in other ways: they could be “born big” or they could eat matter at a rate five times higher than previously thought possible .

According to standard models, supermassive black holes form from the remains of dead stars, which collapse and can form a black hole about a hundred times the mass of the sun. If it grew as predicted, it would take about a billion years for this newly detected black hole to reach its observed size. However, the universe was not yet a billion years old when this black hole was detected.

The GN-z11 galaxy, at the center of which the James Webb Space Telescope discovered the oldest black hole ever detected.

“It’s very early in the universe to see such a massive black hole, so we need to consider other ways it could form,” said Maiolino, of Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory and the Kavli Institute of Cosmology. “The very first galaxies were extremely rich in gas, so they would have been like a buffet for black holes.”

Like all black holes, this young black hole devours matter from its host galaxy to fuel its growth. Yet this ancient black hole gobbles up matter much more vigorously than its siblings of later eras.

The young host galaxy, called GN-z11, shines from a very energetic black hole at its center. Black holes cannot be observed directly, but they are detected by the telltale glow of a swirling accretion disk, which forms near the edges of a black hole. The gas in the accretion disk becomes extremely hot and begins to glow and radiate energy in the ultraviolet range. This strong glow allows astronomers to detect black holes.

The first image of a black hole – or at least the light surrounding its darkness – at the heart of the Messier 87 galaxy.

GN-z11 is a compact galaxy, about a hundred times smaller than the Milky Way, but the black hole is probably hindering its development. When black holes consume too much gas, they push the gas away like a super-fast wind. This “wind” could stop the star formation process, slowly killing the galaxy, but it would also kill the black hole itself, because it would also cut off the black hole’s “food” source.

Maiolino says the gigantic leap forward provided by JWST makes this the most exciting time of his career. “This is a new era: the giant leap in sensitivity, especially in the infrared, is equivalent to going overnight from the Galileo telescope to a modern telescope,” he said. “Before Webb came online, I thought that maybe the universe wasn’t so interesting if you went beyond what we could see with the Hubble Space Telescope. But that didn’t been the case at all: the universe has been quite generous in what it is. shows us, and this is only the beginning.

Maiolino says the sensitivity of the JWST means even older black holes could be discovered in the months and years to come. Maiolino and his team hope to use future JWST observations to try to find smaller “seeds” of black holes, which could help them unravel the different ways black holes might form: whether they are large to begin with or grow rapidly.

More information:

Roberto Maiolino et al, A small, vigorous black hole in the early Universe, Nature (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07052-5. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-024-07052-5. On arXiv: DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2305.12492

Provided by the University of Cambridge

Quote: Astronomers detect oldest black hole ever observed (January 17, 2024) retrieved January 18, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.