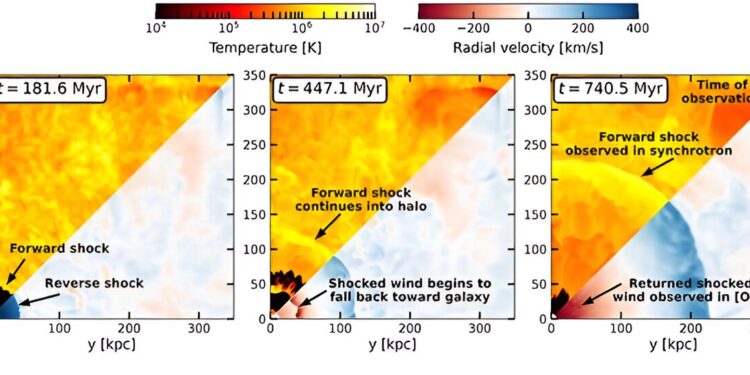

A simulation of star-driven winds at three different periods, starting 181 million years ago. The upper half of each image shows the gas temperature, while the lower half shows the radial velocity. Credit: Cassandra Lochhaas / Space Telescope Science Institute

It’s not every day that astronomers ask, “What is that?” After all, most observed astronomical phenomena are known: stars, planets, black holes and galaxies. But in 2019, the new Australian Square Kilometer Array Pathfinder (ASKAP) telescope detected something no one had ever seen before: circles of radio waves so large they contained entire galaxies at their centers.

While the astrophysics community was trying to determine what these circles were, they also wanted to know “why” these circles were in the first place. Now a team led by Alison Coil, a professor of astronomy and astrophysics at the University of California, San Diego, thinks they’ve found the answer: The circles are shells formed by outgoing galactic winds, perhaps of massive exploding stars known as supernovae. Their work is published in Nature.

Coil and his collaborators studied massive “star” galaxies that can drive these ultrafast outflow winds. Starburst galaxies have an exceptionally high rate of star formation. When stars die and explode, they expel gas from the star and its surroundings into interstellar space. If enough stars explode near each other at the same time, the force of those explosions can push gas out of the galaxy itself into outflow winds, which can travel up to 2,000 kilometers/second.

“These galaxies are really interesting,” said Coil, who is also chair of the Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics. “They occur when two large galaxies collide. The merger pushes all the gas into a very small region, causing an intense burst of star formation. Massive stars burn up quickly, and when they die, they expel their gas in the form of outgoing winds.”

Massive, rare and of unknown origin

Technological developments allowed ASKAP to scan large parts of the sky at very low limits, making odd radio circles (ORCs) detectable for the first time in 2019. The ORCs were enormous: hundreds of kiloparsecs in diameter , where one kiloparsec is equal to 3,260 light years. (for reference, the Milky Way galaxy is about 30 kiloparsecs across).

Several theories have been proposed to explain the origin of ORCs, including mergers of planetary nebulae and black holes, but radio data alone could not distinguish between the theories.

Coil and his collaborators were intrigued and thought it was possible that the radio rings were a development of later stages of the starburst galaxies they had studied. They began studying ORC 4, the first discovered ORC observable from the Northern Hemisphere.

Until now, ORCs were only observed by their radio emissions, without any optical data. Coil’s team used a field spectrograph built into the WM Keck Observatory in Maunakea, Hawaii, to examine ORC 4, which revealed a huge amount of compressed, heated, highly luminous gas, much more than previously thought. ‘we see in the average galaxy.

With more questions than answers, the team set to detective work. Using optical and infrared imaging data, they determined that the stars inside the ORC 4 galaxy were about 6 billion years old. “There was an explosion of star formation in this galaxy, but it ended about a billion years ago,” Coil said.

Cassandra Lochhaas, a postdoctoral fellow at the Harvard & Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics who specializes in the theoretical aspect of galactic winds and co-author of the paper, ran a suite of numerical computer simulations to reproduce the size and properties of the radio at large scale. ring, including the large amount of cold, shocked gas in the central galaxy.

His simulations showed that galactic winds blew for 200 million years before stopping. When the wind stopped, a forward shock continued to propel high-temperature gas out of the galaxy and created a radio ring, while a reverse shock caused cooler gas to fall back onto the galaxy . The simulation ran for 750 million years, within the approximate range of ORC 4’s estimated 1 billion year stellar age.

“For this to work, you need a high mass exit rate, which means it ejects a lot of material very quickly. And the surrounding gas just outside the galaxy needs to be low density, otherwise the shock stops. Those are the two key factors,” Bobine said.

“It turns out that the galaxies we studied have high mass outflow rates. They’re rare, but they exist. I really think this indicates that ORCs come from some kind of galactic outflow.”

Not only can outflow winds help astronomers understand ORCs, but ORCs can also help astronomers understand outflow winds.

“ORCs allow us to ‘see’ winds through radio data and spectroscopy,” Coil said.

“This can help us determine how common these extreme galactic winds are and what the life cycle of the wind is. They can also help us learn about galactic evolution: do all massive galaxies go through an ORC phase ?Do spiral galaxies become elliptical when they no longer form stars?I think we can learn a lot about ORCs and learn from ORCs.

More information:

Alison Coil, Ionized gas extends 40 kpc in strange radio circle host galaxy, Nature (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06752-8. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06752-8

Provided by University of California – San Diego

Quote: Space oddity: discovering the origin of the rare radio circles in the universe (January 8, 2024) retrieved January 9, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.