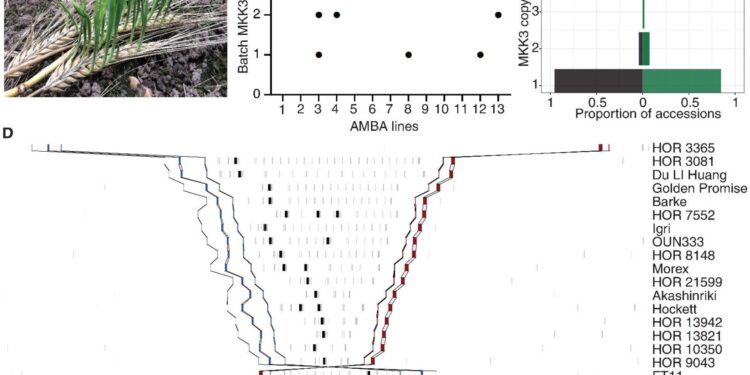

Complexity of the MKK3 locus in barley. Credit: Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adx2022

Every year, billions of dollars of crops around the world perish due to preharvest sprouting (PHS), a phenomenon in which grains or seeds germinate on the plant before harvest. The process is triggered by various factors, such as hot and humid weather, which can spoil crops and threaten the world’s food supply. But that could be a thing of the past, as a team of researchers, mainly from the Carlsberg Research Laboratory in Denmark, has discovered the genetic mechanism that controls when barley should germinate.

Self-inflicted problem

PHS is entirely a problem of our own making. When early farmers domesticated barley, they wanted a crop that would germinate shortly after planting. So they selected varieties with less natural seed dormancy, a pause that prevents seeds from germinating until conditions are ideal. Although this allows farmers to plant quickly after harvest, sometimes yielding two harvests, it has a considerable disadvantage.

If weather conditions are perfect before harvest, the entire crop begins to germinate early on the stalk. This is a problem because even if you could pick it early, the grain is often too wet to store or has already begun the biochemical changes that ruin its food or brewing quality.

To better understand the causes of PHS, scientists focused on MKK3, a gene known to play a role in controlling dormancy in barley and other grains. They analyzed the DNA of more than 1,000 types of barley from farms and seed banks around the world.

They also grew barley varieties in fields for several seasons, subjecting half to conditions likely to cause PHS. This allowed them to compare affected grains to normal grains. Back in the lab, the researchers studied gene expression and measured protein activity to see how MKK3 genes directly influenced dormancy.

Genetic information

The main conclusions, according to their study published in the journal ScienceThis is because dormancy is controlled by multiple versions of MKK3, not just one. Wild barley has one, while domesticated varieties have several. This means that the more MKK3 genes a barley plant has, the stronger the germination signal and the shorter the seed dormancy.

The study also examined how MKK3 variants spread in response to climate and the needs of ancient farmers. Some were hyperactive and were chosen by Northern European farmers for their superior malting quality. Others were less active (high dormancy) and favored by farmers in humid climates, such as East Asia. This meant that crops could survive monsoons without germinating early.

With this extensive genetic knowledge, the study authors hope that today’s farmers will be able to grow the perfect barley variety for any region. “Our work shows that understanding the genetic complexity of dormancy can help breeders develop barley that is both productive and resilient to climate change.”

Written for you by our author Paul Arnold, edited by Gaby Clark, and fact-checked and revised by Robert Egan, this article is the result of painstaking human work. We rely on readers like you to keep independent science journalism alive. If this reporting interests you, consider making a donation (especially monthly). You will get a without advertising account as a thank you.

More information:

Morten E. Jørgensen et al, Postdomestication selection of MKK3-shaped seed dormancy and end-use traits in barley, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adx2022

© 2025 Science X Network

Quote: Discover the genetic mechanism that causes early germination of barley crops (November 7, 2025) retrieved November 8, 2025 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.