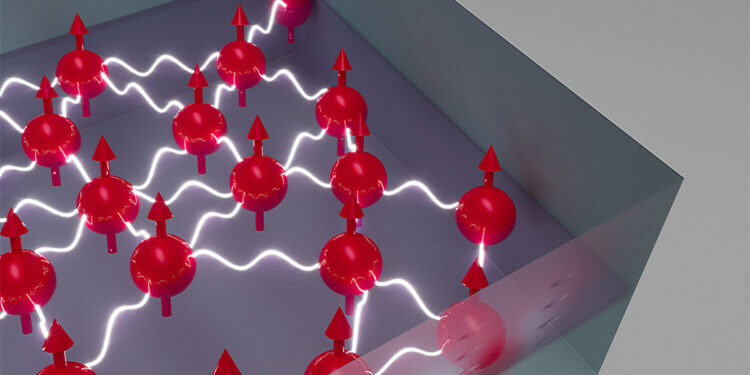

Artist’s conceptual illustration showing a two-dimensional collection of interacting spins in a lattice of diamonds. Credit: Brian Long

The path to realizing practical quantum technologies begins with understanding the fundamental physics that governs quantum behavior and how these phenomena can be exploited in real materials.

In the lab of Ania Jayich, Bruker Professor of Science and Engineering, Elings Professor of Quantum Science, and co-director of the National Science Foundation Quantum Foundry at UC Santa Barbara, that material of choice is lab-grown diamond.

Working at the intersection of materials science and quantum physics, Jayich and his team explore how artificial defects in diamond, known as spin qubits, can be used for quantum sensing. Among the lab’s most notable researchers is Lillian Hughes, who recently received her Ph.D. and will soon begin postdoctoral work at the California Institute of Technology, has made a major breakthrough in this effort.

In a series of three articles co-authored with Jayich, including one published in Physical examination (PRX) in April and the second and third in Nature in October — Hughes demonstrates, for the first time, how not just individual qubits but two-dimensional ensembles of many defects can be arranged and entangled in diamond.

This breakthrough realizes solid-state metrological quantum advantage, marking an important step toward the next generation of quantum technologies.

Well-designed defects

“We can create a configuration of central nitrogen vacancy (NV) spins in diamonds with control over their density and dimensionality, such that they are densely packed and confined at depth in a 2D layer,” Hughes said. “And because we can design how the defects are oriented, we can design them to exhibit non-zero dipolar interactions.”

This achievement was the subject of PRX article, entitled “A set of strongly interacting two-dimensional dipole spins in a (111)-oriented diamond.”

The NV center of diamond consists of a nitrogen atom, which replaces a carbon atom, and a missing adjacent carbon atom (the vacancy).

“The NV center defect has a few properties, one of which is a degree of freedom called spin, a fundamentally quantum concept. In the case of the NV center, spin is very long-lived,” Jayich said.

“These long-lived spin states make NV centers useful for quantum sensing. The spin couples to the magnetic field we are trying to detect.”

The possibility of using spin degree of freedom as a sensor has existed since the invention of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the 1970s, Jayich explained, noting that MRI works by manipulating the alignment and energy states of protons, then detecting the signals they emit as they return to equilibrium, creating an image of an internal body part.

“Previous quantum sensing experiments conducted in a solid-state system all used single spins or sets of non-interacting spins,” Jayich said.

“What’s new here is that because Lillian was able to develop and design these very strongly interacting dense sets of spins, we can actually exploit the collective behavior, which provides an additional quantum advantage, allowing us to use the phenomenon of quantum entanglement to achieve better signal-to-noise ratios, providing greater sensitivity and enabling better measurement.”

Lillian Hughes, left, and Ania Jayich, right, using laser confocal microscope, interview NV centers after training. Credit: Lilli Walker

The type of entanglement-assisted detection that Hughes’ work enables has already been demonstrated in gas-phase atomic systems.

“Ideally, for many target applications, your sensor should be easy to integrate and bring closer to the system being studied,” Jayich said.

“It is much easier to do this with a solid material, such as diamond, than with gas-phase atomic sensors on which, for example, GPS is based. Additionally, atomic sensors require significant auxiliary hardware for confinement and control, such as vacuum chambers and many lasers, which makes it difficult to bring a nanoscale atomic sensor close to a protein, for example, prohibiting imaging at high spatial resolution.”

In the Jayich lab, the focus is on using diamond sensors to study materials-based electronic effects and phenomena. But, analogous to placing a solid-state sensor in a cell, Jayich said, “You can place material targets near a nanoscale diamond surface, bringing them very close to underground NV centers.” It is therefore very easy to integrate this type of diamond quantum sensor with a variety of interesting target systems.

“A solid-state magnetic sensor of this type could be very useful for probing, for example, biological systems,” Jayich said.

“Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) is based on the detection of very small magnetic fields originating from the constituent atoms, for example in biological systems. Such an approach is also useful if you want to understand new materials, whether electronic materials, superconducting materials or magnetic materials that could be useful for various applications.”

Press to silence the noise

Any measurement contains associated noise which limits the measurement to a certain degree of precision. A fundamental source of noise, called quantum projection noise, limits the precision of measurements to a value called the standard quantum limit, a value which is conventionally reduced by the square root of N, the number of quantum sensors used in the measurement.

However, if we manage to design a particular form of interaction between the sensors, it becomes possible to exceed the standard quantum limit for N non-entangled sensors. A clever way to achieve this is to “compress” the noise amplitude by inducing correlations between particles and producing a spin compression state.

“It’s like trying to measure something with a meter stick that has gradations spaced a centimeter apart; those gradations spaced a centimeter apart actually correspond to the amplitude of the noise in your measurement. You wouldn’t use such a meter stick to measure the size of an amoeba, which is much smaller than a centimeter,” Jayich said.

“By squeezing, silencing the noise, you effectively use the interactions of quantum mechanics to ‘crush’ that meter, creating finer gradations and allowing you to measure smaller things more precisely.”

The second article describes another type of metrological gain that can be obtained using the same system, in this case, by amplifying the signal strength without increasing the noise level to perform a better measurement. In the amoeba example given above, the amplification of the signal has the effect of making the amoeba larger, so that the measuring stick with its one centimeter gradation can now be used to measure it.

In terms of possible real-world applications, Jayich said: “I don’t think the anticipated technical challenges will prevent demonstrating a quantum advantage in a useful sensing experiment in the near future. This is mainly about making the signal amplification louder or increasing the amount of compression. One way to achieve this is to control the position of the spins in the 2Dxy plane, forming a regular lattice.

“There is a hardware challenge here, in that because we can’t dictate exactly where the rotations are going to incorporate, they incorporate somewhat randomly into a shot,” Jayich added.

“This is something we are currently working on, so that eventually we can have a grid of these spins, each placed at a specific distance from each other. This would provide an exceptional challenge for realizing a practical quantum advantage in sensing.”

More information:

Haoyang Gao et al, Signal amplification in a solid-state sensor by asymmetric many-body echo, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09452-7

Weijie Wu et al, Spin compression in a set of nitrogen vacancy centers in diamond, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09524-8

Lillian B. Hughes et al, Strongly interacting two-dimensional dipole spin sets in a (111) oriented diamond, Physical examination (2025). DOI: 10.1103/physrevx.15.021035

Provided by University of California – Santa Barbara

Quote: A new dimension for spin qubits in diamond (October 30, 2025) retrieved on October 30, 2025 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.