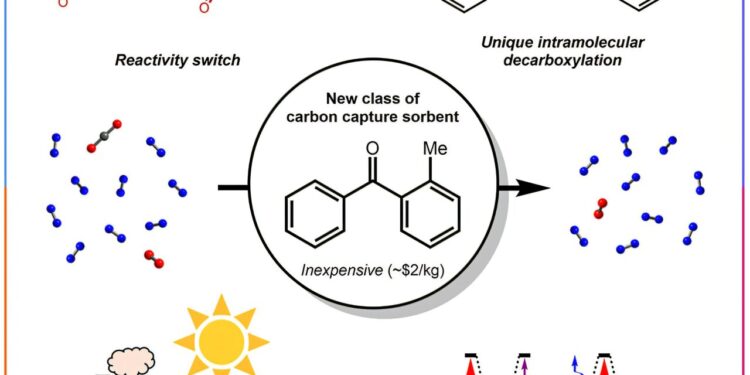

Credit: Chem (2025). DOI: 10.1016 / J.CHEMPR.2025.102583

The current methods of carbon capture and release are expensive and so strong energy that they often require, counterproductors, the use of fossil fuels. Inspired by plants, Cornell researchers have assembled a chemical process that can fuel carbon capture with an abundant, clean and free source of energy: sunlight.

Research could considerably improve the current methods of carbon capture – an essential strategy in the fight against global warming – by reducing net costs and emissions.

In the study, published in ChemResearchers have discovered that they can separate carbon dioxide from industrial sources by imitating the mechanisms that plants use to store carbon, using sunlight to make a stable eno -stable molecule enough to “grasp” carbon.

They also used sunlight to drive an additional reaction which can then release carbon dioxide for storage or reuse. This is the first light separation system for the capture and release of carbon. Bayu Ahmad graduate students, MS ’23, are the first author.

“From the point of view of chemistry, it is completely different from what anyone else is in carbon capture,” said the main author Phillip Milner, an associate professor of chemistry and chemical biology at the College of Arts and Sciences. “The whole mechanism was Bayu’s idea, and when he came to me originally, I thought it would never work. It works completely.”

Carbon dioxide is difficult to capture because it is inert, said Milner, which has led researchers and an industry to amines – organic compounds and ammonia derivatives which contain nitrogen – which react selectively with carbon dioxide and can draw it from many compounds. But amines are not stable in the presence of oxygen and do not last, requiring energy production more and more amines.

“From the start, our laboratory tried to think about how we can use our intuition as chemists to find alternative pathways for the capture of carbon dioxide,” said Milner. “We essentially have a motto of” everything except amines “.

The carbon capture reaction uses the same mechanism as the Rubisco enzyme, crucial for photosynthesis, uses to fix carbon in plants. To release carbon, researchers have changed the pH to activate decarboxylation or elimination of a carboxyl group. They used a cheap sorbant, 2-methylbenzophenone, and found that the carbon capture rate in the new system was equal or better than other light-oriented technologies. The system also did not require an additional cooling between the release and capture stages, a major limitation of other methods of carbon capture and release.

The researchers tested the system using samples of combined heat and electricity construction conduits of Cornell, a power plant on the campus that burns natural gas and found that it managed to isolate carbon dioxide. Milner said that this step was significant, as many promising methods for capturing carbon in the laboratory fail when they are on the level of real world samples with traces.

Milner and his team plan to stage the reaction on what looks like a solar panel, but which would capture carbon instead of producing electricity. As aninural Family Fellow of the Semlitz family at the Cornell Atkinson Center for Sustainability, Ahmad works with partners of Cornell SC Johnson College of Business to explore marketing.

“We would really like to arrive at the point where we can remove the carbon dioxide from the air, because I think it is the most practical,” said Milner. “You can imagine entering the desert, you put these panels that aspire carbon dioxide out of the air and transform it into carbon dioxide at high pure pressure. We could then put it in a pipeline or convert it into something on site.”

The Milner laboratory also explores how the food system could be applied to other gases, as separation leads to 15% of global energy consumption.

“There are a lot of opportunities to reduce energy consumption using light to drive these separations instead of electricity,” said Milner.

Milner is part of an effort to make duct samples from the combined building of heat and electricity from Cornell available to researchers and startups studying carbon capture in Cornell and beyond.

“It is really difficult to obtain real industry combustion gases, because companies do not want people to know what comes out of their power plants,” said Milner. “But Cornell is not a business – so it is something unique that we can offer and that we hope to be operational in the next year.”

More information:

Bayu Iz Ahmad et al, an approach entirely focused on light to separate carbon dioxide from emission flows, Chem (2025). DOI: 10.1016 / J.CHEMPR.2025.102583

Chem

Supplied by Cornell University

Quote: System supplied by sunlight imitates power carbon capture factories (2025, May 12) recovered on May 13, 2025 from

This document is subject to copyright. In addition to any fair program for private or research purposes, no part can be reproduced without written authorization. The content is provided only for information purposes.