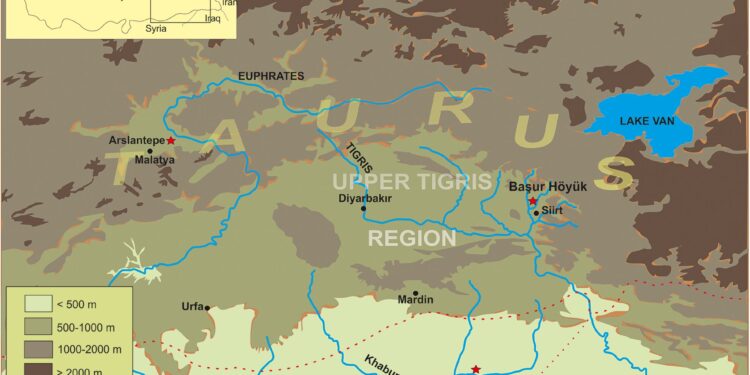

The location of Başur Höyük on the upper tiger. Credit: Cambridge Archaeological Journal (2025). DOI: 10.1017 / S0959774324000398

University College of London, the University of the Central Lancashire, the Ege University and other institutions have discovered that radical inequalities existed in burial practices in adolescents in Anatolia at the beginning of bronze, prior to the development of social hierarchies in broader society. The discovery questions traditional understanding of the way in which societies are emerged.

Archeology often describes the rise in power of power and hierarchy at the start of Mesopotamia as a passage of small communities equal to large complex societies led by cities, kings and bureaucrats. A large part of this point of view comes from uneven cities and burials in the south of Mesopotamia, where an increasing disparity in wealth, a centralized rule and early legal codes coincide with urban development.

In the study, “inequality at the dawn of the Bronze Age: the case of Başur Höyük, a” royal “cemetery on the sidelines of the Mesopotamian world”, published in the Cambridge Archaeological JournalThe researchers carried out an archaeological, anthropological and genetic analysis combined with an early bronze age cemetery to study the first signs of social hierarchy.

The analysis focused on 18 tombs in Başur Höyük, dated approximately 3100 to 2800 BCE, including cists and pit-pit fos, some containing several individuals buried in subordinate positions.

The team applied an old DNA sequencing, an analysis of the isotopes of strontium and lead, and medico-legal osteological assessments, in parallel with a detailed study of the composition of pearls, metallurgical artifacts and spatial burial configurations to assess the indicators of social differentiation and hierarchical structuring.

A selection of copper -based metal goods from Başur Höyük. Credit: Cambridge Archaeological Journal (2025). DOI: 10.1017 / S0959774324000398

The tombs built with stone contained large quantities of metallic weapons, ornaments and ornate pearls. Most of the primary individuals in these tombs were adolescents aged 12 to 16, often dressed in clothing made from non -local materials.

Adjacent burials have shown evidence of acute trauma in accordance with ritual death. DNA analysis has not revealed any close biological relationship between individuals, and sexual determinations have shown both men and women, without diagram linking biological sex to funeral treatment. The results of the isotopes said that many had grown outside the local region.

The results suggest that radical inequality has emerged in funeral rituals without proof of a broader political hierarchy. The richly furnished tombs were concentrated in adolescents, without any indication of elite lines, centralized authority or hereditary status.

The researchers propose that the cemetery reflect something unexpected. The adolescent-centered burials can indicate an age-based social structure, or perhaps a symbolic reverence for young people who existed outside of formal political life.

Proofs of wealth and sacrificial violence in these tombs suggest a form of social differentiation which has emerged beyond institutions such as cities, dynasties or bureaucraties, raising questions about the way in which inequality first took shape in ritual and ceremonial circles.

The authors warn that “there is no longer clear as to the nature of these deposits, and the rituals that have given birth to them, but one thing that we can already conclude is that the identification of Başur Höyük as a site of an archaeological context ‘Royal’ ‘is also very improbable.

The regional adult elite burials that appear after early bronze age echo many ornaments and practices observed in Başur Höyük, including the presence of ritually killed attendants.

The transfer of veneration of the fallen youth of society to adults who had accumulated wealth and power suggest more than just consolidation of dynastic authority. It can reflect a deeper reorganization of social values - an appropriation of status with wealth and power that have replaced honor once reserved only for children in society.

More information:

David Wengrow et al, inequality at the dawn of the Bronze Age: the case of Başur Höyük, a “royal” cemetery on the sidelines of the Mesopotamian world, Cambridge Archaeological Journal (2025). DOI: 10.1017 / S0959774324000398

© 2025 Science X Network

Quote: The old tombs in Anatolia suggest that the reverence for young elite burials preceded (2025, April 1) recovered on April 2, 2025 from

This document is subject to copyright. In addition to any fair program for private or research purposes, no part can be reproduced without written authorization. The content is provided only for information purposes.