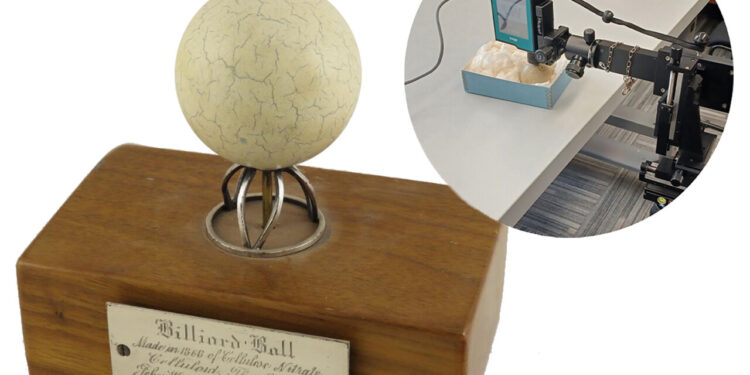

Original 1868 billiard ball by John Wesley Hyatt and its in situ analysis by portable Raman spectroscopy. Credit: Smithsonian Institution

In the 19th century, the market for ivory products reached an alarming point. This high demand led to the search for artificial substitutes, but the properties of ivory were almost impossible to replicate. The most important substitutes came from Alexander Parkes and John Wesley Hyatt, inventors of the first artificial plastics: parkesin and celluloid.

These first plastics were made from cellulose nitrate and camphor. The importance of parkesin and celluloid objects in the history of plastic is well understood; it is for this reason that they have been collected by eminent museums around the world.

Hyatt’s initial goal was to replace ivory billiard balls. The properties of ivory were highly valued, especially in the game of billiards, which depended entirely on the mechanics of this material. However, the difficulties associated with the acquisition of ivory, its selection and processing, as well as its sensitivity to relative humidity and temperature fluctuations which lead to cracking and breakage, do not were not ideal.

In addition, the number of players was increasing and the industry knew that the supply was not inexhaustible. At the National Museum of American History resides the original billiard ball developed by Hyatt. It is likely to be the first celluloid object ever created, dating from 1868, and the founding object of the plastics industry. However, its composition was unknown.

Historians and scientists have written about Hyatt’s billiard balls because of their importance in the history of plastics. However, because they did not know their composition, they could not determine the extent to which substitute materials had been used. For decades, several models have been proposed, such as billiard balls made of pure celluloid or billiard balls made of shellac compositions coated with a cellulose nitrate solution.

The common interpretation was that Hyatt’s original billiard ball failed because the properties of celluloid, or any other alleged material, could not approach the mechanical properties of ivory. In a recent study published in Nexus PNASwe determined the composition of the Hyatt billiard balls and proposed a different interpretation.

John Wesley Hyatt’s first composite

To determine the composition of the original Hyatt billiard ball dating from 1868, we needed the support of the Smithsonian Institution, its authorization to acquire micro-samples, that is to say samples invisible to the eye. naked eye, and modern analytical techniques, namely elemental and molecular spectroscopies and protein analyses. mass fingerprinting.

The results were surprising: Hyatt’s early experiments with billiard balls resulted in the development of a first example of a reinforced polymer composite material based on cellulose nitrate, a cellulose-derived polymer that holds the ball together; camphor, a plant material acting as a plasticizer for cellulose nitrate; and ground bovine bone, an animal by-product providing the necessary mechanical properties to the system.

We quantified the proportions of ground bone to celluloid by micro-Fourier transformed infrared spectroscopy and found a correlation with a formulation patented by Hyatt on May 4, 1869, of 75% ground bone to 25% bone nitrate. cellulose by weight. We proposed that this composite be called reinforced celluloid. But was it a success?

A reinforced celluloid silver ball

By carefully examining written documents related to the world of billiards, we found references to trade names of billiard balls sold from the 1880s to the 1960s, distinctly different from ivory, but whose compositions were also enigmatic: Bonzoline, Crystalate and Ivorylene. All of these billiard balls were directly or indirectly linked to the Albany Billiard Ball Company, established by Hyatt in 1868 in Albany, New York, United States. We analyzed these pool balls and found that their compositions were surprisingly consistent with Hyatt’s reinforced celluloid composite.

The realization that reinforced celluloid had been sold for nearly 90 years proved the commercial success of Hyatt’s 1868 composite. Examining the stories surrounding professional gamers and their material choices has allowed us to understand how this material entered commerce and culture.

Initially, there was prejudice against the use of the artificial substitute. The match between Charles Dawson and John Roberts Jr. in 1899, known as the Match of the Century, epitomized this problem. Roberts Jr. wanted to play with Bonzoline, and Dawson challenged: “Who has heard of a money match of any importance played with Bonzoline balls?”

However, the reinforced celluloid billiard balls were more uniform than their ivory counterparts. This advantage led to better performances from Roberts Jr. and other influential players. Over time, even Dawson made Bonzoline billiard balls known. The reinforced celluloid was efficient and cost half the price of ivory, which promoted the development of the game of billiards throughout the world and contributed to the survival of elephants. Hyatt made a buck with his inventive shot at an ivory substitute.

An inspiration for the future?

Look at a contemporary billiard ball from macro to micro scale. It is likely composed of a phenol-formaldehyde matrix, filler, and other additives, a system very similar to reinforced celluloid. Although the qualities of phenol-formaldehyde plastics were crucial in surpassing earlier billiard ball materials, nowadays environmental questions have been raised regarding this material as a plastic pollutant.

If a young engineer, just as John Wesley Hyatt did 155 years ago, aspires to develop an innovative and environmentally sustainable alternative to contemporary billiard ball materials using raw materials derived from bioresources, the example set by Hyatt is a rich source of inspiration. composition. Not only because it demonstrates the feasibility of such an endeavor, but also because it illustrates the challenges that must be overcome to achieve a transformative invention.

This story is part of Science X Dialog, where researchers can report the results of their published research articles. Visit this page for more information about ScienceX Dialog and how to get involved.

More information:

Artur Neves et al, Best billiard ball of the 19th century: composite materials based on celluloid and bone as substitutes for ivory, Nexus PNAS (2023). DOI: 10.1093/pnasnexus/pgad360

Artur Neves holds a PhD in Conservation and Restoration of Cultural Heritage awarded by NOVA University in Lisbon, Portugal, in 2023. In 2022, he received a Fulbright Research Fellowship. Hosted by the University of Maryland Department of History, it has worked with cultural institutions for the interdisciplinary study of celluloid heritage, including the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History. He is currently a postdoctoral researcher in the project “Plastic metamarphoses: reality and multiple approaches to a material” working on the culture of plastic materials in Portugal.

Quote: The first successful substitutes for ivory billiard balls were made with celluloid reinforced with crushed cattle bones (November 24, 2023) retrieved November 25, 2023 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.