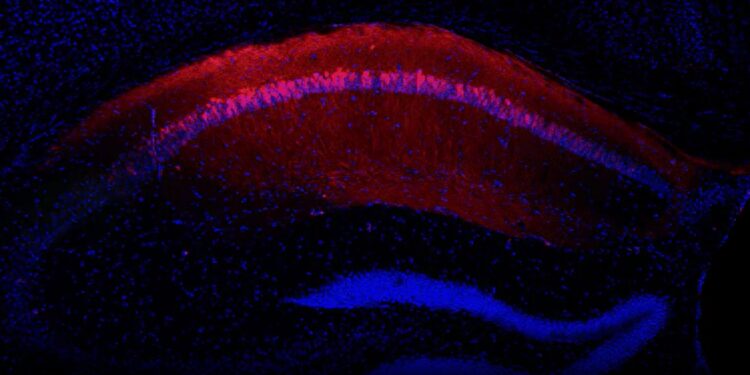

The memory center of a mouse brain. Credit: P. Kassraian et al., Zuckerman Institute at Columbia

How to distinguish threat from security? This is an important question not only in our daily lives, but also for human disorders related to fear of others, such as social anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The microscope image accompanying this press release, from the laboratory of Steven A. Siegelbaum, Ph.D., at Columbia’s Zuckerman Institute, shows a powerful technique scientists are using to help us find an answer.

The scientists were studying the hippocampus, an area of the brain that plays a key role in memory in humans and mice. Specifically, they focused on the CA2 region, important for social memory, the ability to remember other individuals, and on the CA1 region, important for remembering places.

In this new study, researchers reveal for the first time that CA1 and CA2 respectively encode places and individuals linked to a threatening experience. The results show that beyond the simple recognition of individuals, CA2 allows more complex aspects of social memory to be recorded: in this case, whether another individual is safe or at risk. The scientists published their results on October 15 in the journal Natural neuroscience.

“It is vital for all species that live in social communities, including mice and humans, to have a social memory that can help avoid future experiences with others that could prove harmful, while also remaining open to individuals who might be beneficial,” said Pegah Kassraian, Ph.D., a postdoctoral researcher in the Siegelbaum lab and lead author of the new study. “Frightening memories are important for survival and contribute to our safety.”

To study the origin of fearful social memories in the brain, Dr. Kassraian and his colleagues gave each mouse a choice. They might rush to a location, encounter another mouse unfamiliar to them, and receive a mild foot shock (much like a static electricity zap that people might receive after walking on a carpet and touching a doorknob ). Rushing in the opposite direction to meet another stranger was safe. Normally, mice quickly learned to avoid strangers and places associated with shocks, and these memories lasted at least 24 hours.

To determine where these memories were stored in the hippocampus, the researchers genetically modified the mice to allow them to selectively delete the CA1 or CA2 regions. Surprisingly, disabling each region had very different effects. When the scientists silenced CA1, the mice could no longer remember where they had been zapped, but they could still remember which stranger was associated with the threat. When they silenced CA2, the mice remembered where they had been shocked, but began to be indiscriminately afraid of the two strangers they encountered.

These new findings reveal that CA2 helps mice remember whether past encounters with other people were threatening or harmless. The results are also consistent with previous research detailing how CA1 houses placement cells, which encode locations.

Previous research has implicated the CA2 in various neuropsychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia and autism. The new study suggests that further investigation of CA2 could help scientists better understand social anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and other conditions that can lead to social withdrawal.

“It is possible that symptoms of social withdrawal are related to an inability to distinguish between who is a threat and who is not,” said Dr. Siegelbaum, also a professor and chair of the Department of Neuroscience at Vagelos College. of Physicians and Surgeons of Columbia. . “Targeting CA2 could be a useful way to diagnose or treat disorders related to fear of others.”

More information:

The hippocampal region CA2 distinguishes between social threat and social security, Natural neuroscience (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41593-024-01771-8. www.nature.com/articles/s41593-024-01771-8

Provided by Columbia University

Quote: Fearful memories of others observed in mouse brains – study identifies where different types of memories begin (October 15, 2024) retrieved October 15, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.