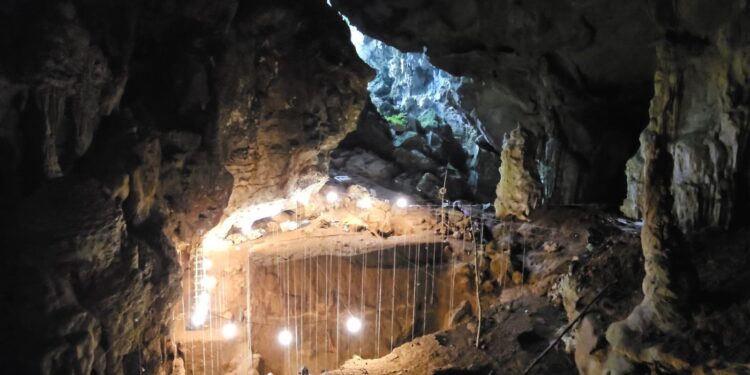

Local archaeologists excavating in the Tam Pà Ling cave, Laos. Credit: Vito Hernandez, Flinders University

Studying microscopic layers of earth excavated from Tam Pà Ling Cave in northeast Laos has allowed a team of Flinders University archaeologists and their international colleagues to better understand some of the earliest evidence for the presence of Homo sapiens in mainland Southeast Asia.

The site, studied for 14 years by a team of Laotian, French, American and Australian scientists, has produced some of the first fossil evidence of our direct ancestors in Southeast Asia.

Now, a new study, led by Ph.D. candidate Vito Hernandez and Associate Professor Mike Morley of the College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences reconstructed soil conditions in the cave between 52,000 and 10,000 years ago. The work appears in Scientific reviews of the Quaternary.

“Using a technique known as microstratigraphy at the Flinders Microarchaeology Laboratory, we were able to reconstruct the condition of the caves in the past and identify traces of human activities in and around Tam Pà Ling,” says Hernandez. “It also helped us determine the precise circumstances in which some of the earliest modern human fossils discovered in Southeast Asia were deposited at depth.”

Microstratigraphy allows scientists to study dirt in great detail, allowing them to observe structures and features that preserve information about past environments, and even traces of human and animal activities that might have been overlooked during the excavation process due to their tiny size.

Author Associate Professor Mike Morley. Credit: Flinders University

The human fossils discovered at Tam Pà Ling were deposited in the cave between 86,000 and 30,000 years ago, but until now researchers have not carried out a detailed analysis of the sediments surrounding these fossils to understand how they were deposited in the cave or the environmental conditions of the time.

The results reveal that conditions in the cave fluctuated considerably, from a temperate climate with frequently wet soils to a seasonally dry climate.

“This change in environment influenced the interior topography of the cave and would have impacted how sediments, including human fossils, were deposited in the cave,” says Associate Professor Morley.

“How Homo sapiens was buried deep within the cave has long been debated, but our sediment analysis indicates that the fossils were carried into the cave as loose sediment and debris accumulating over time , probably carried by water from the surrounding hills during periods of heavy rain.

Excavations at Tam Pà Ling. Credit: Vito Hernandez, Flinders University

The team also identified preserved micro-traces of charcoal and ash in the cave’s sediments, suggesting that either wildfires occurred in the area during drier periods or that humans visiting the cave were able to use fire, either in the cave or near the entrance. .

“This research has allowed our team to develop unprecedented insights into the dynamics of our ancestors as they dispersed across the ever-changing forest covers of Southeast Asia and during periods of climate instability regional variable”, explains assistant professor Fabrice Demeter, co-author of the study. , paleoanthropologist from the University of Copenhagen, who since 2009 has led the team of international researchers studying Tam Pàn Ling.

More information:

Late Pleistocene-Holocene (52-10 ka) microstratigraphy, fossil taphonomy and depositional environments of Tam Pa Ling Cave (north-eastern Laos), Scientific reviews of the Quaternary (2024).

Provided by Flinders University

Quote: Fossils and fires: insights into modern human activity in the jungles of Southeast Asia (October 9, 2024) retrieved October 10, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.