Credit: Immunity (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.immuni.2024.08.017

Researchers at Monash University have developed a new technique to improve the effectiveness of traditional and mRNA-based vaccines in animal models.

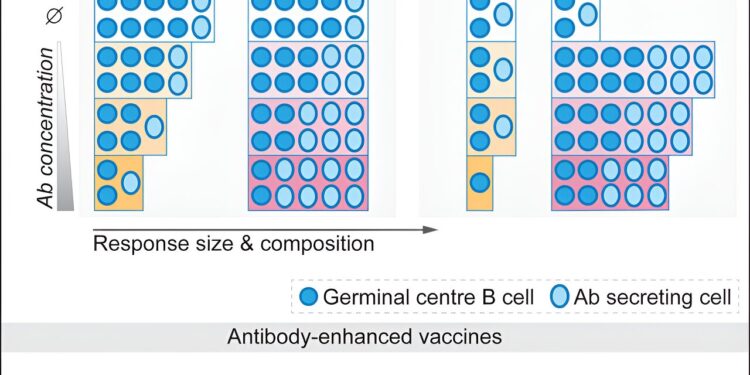

Published in ImmunityThe study found that adding low doses of a vaccine-specific antibody to a COVID-19 vaccine stimulated the immune system’s B cells, which are responsible for generating antibodies to fight viral infections.

The results of this study highlight the potential of antibodies as vaccine components to boost the immune response.

“A key challenge in vaccine design is ensuring sufficient activation and duration of B cell responses to achieve the quantity and quality of antibodies needed for protection,” said lead author Dr Isaak Quast, from Monash University’s Department of Immunology.

“Adding specific antibodies to the vaccine is like adding a red flag and making it really obvious to the B cells that they need to go into action.

“This method stimulates B cells that would otherwise fail to actively participate in the immune response, potentially enabling them to recognize new parts of invading viruses, thereby increasing protective immunity.”

Lead author Dr. Alexandra Dvorscek said most vaccines offer specificity and efficacy, but achieving broad reach is often difficult. “When you have viruses like influenza or SARS-CoV-2, which can vary significantly from year to year or even over shorter periods of time, and can cause significant harm, we need that recognition and that broad response,” Dvorscek said.

One structure that is commonly misrecognized by the immune system is the conserved parts of viral proteins, the “essence” of a virus that remains stable despite new variants that emerge as a virus evolves to evade immune detection.

Dr. Dvorscek said that like adjuvants, which enhance the immune system’s response to vaccination, adding antibodies prolongs immune responses and triggers greater antibody production.

“The beauty of this technique is that in collaboration with Dr Deborah Burnett at the Garvan Institute in Sydney, we have shown that it works for both traditional vaccines and mRNA-based ones such as those targeting SARS-CoV-2,” she said.

“This obviously has implications for existing vaccines and those in development: we can exploit this technology to stimulate immune responses in a safe and highly targeted way.

“Beyond stimulating B cell responses, antibodies influence targeted viral structures and ensure that the immune system spreads its response across multiple parts of the pathogen. Our study provides new insights into how this happens and how we can use it to direct antibody production to the sites that need to be targeted for broad protective immunity.”

“We have found a way to potentially use the immune system’s own way of doing things, antibodies, to influence how our bodies respond to a vaccine. This could be particularly relevant for people who respond poorly to vaccines, such as the elderly or those who are immunocompromised. Future research will need to test this.”

Dr Quast said that although so far this research has only been tested in animal models, it could also facilitate the development of vaccines targeting pathogen structures that are not sufficiently recognised by our immune system.

“In a diverse human population, some people will always respond better than others, and this method could help ensure that a greater proportion of the population develops a ‘good and sufficient’ immune response to protect themselves,” he said.

“The method described in this paper has the potential to dramatically increase these typically poor responses, and it works equally well with mRNA vaccines as it does with traditional vaccines. One example we use is the amplification of a SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine developed by study co-author and Monash Institute of Pharmaceutical Sciences Professor Colin Pouton.”

More information:

Alexandra R. Dvorscek et al., Conversion of vaccines from low to high immunogenicity by epitope-complementary antibodies, Immunity (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.immuni.2024.08.017

Provided by Monash University

Quote:Researchers ‘speed up’ vaccine delivery by coaxing ‘bystander’ immune cells into action in animal models (2024, September 23) retrieved September 23, 2024, from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.