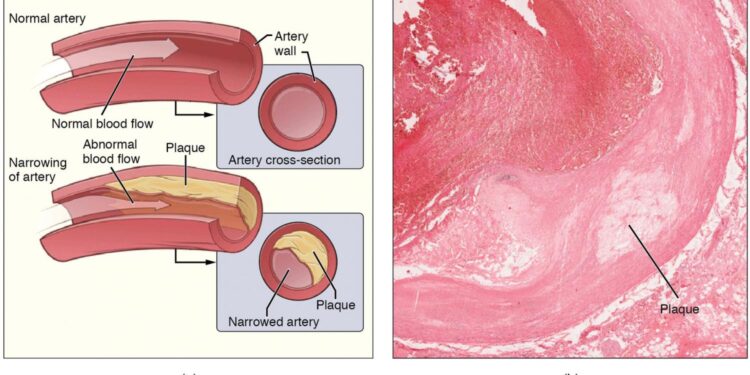

Atherosclerosis is a disease that affects the cardiovascular system. If atherosclerosis occurs in the coronary arteries (which supply blood to the heart), it can lead to angina or, in severe cases, a heart attack. Credit: Wikipedia/CC BY 3.0

Exposure to metals from environmental pollution is associated with increased calcium buildup in the coronary arteries at a level comparable to traditional risk factors such as smoking and diabetes, according to a study from Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health.

The results confirm that metals in the body are associated with the progression of plaque buildup in arteries and potentially offer a new strategy for the management and prevention of atherosclerosis. The results are published in the journal Journal of the American College of Cardiology.

“Our findings underscore the importance of considering metal exposure as a significant risk factor for atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease,” said Katlyn E. McGraw, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow in environmental health sciences at Columbia Mailman School and lead author of the study. “This could lead to new prevention and treatment strategies targeting metal exposure.”

Atherosclerosis is a disease characterized by narrowing and hardening of the arteries due to a buildup of plaque, which can restrict blood flow and cause clots to form. It is an underlying cause of heart attacks, strokes, and peripheral artery disease (PAD), the most common forms of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Atherosclerosis causes coronary artery calcium (CAC), which can be measured noninvasively over time to predict future cardiac events.

Exposure to environmental pollutants such as metals is a newly recognized risk factor for cardiovascular disease, but there is not much research on its association with CAC.

Researchers in this study sought to determine how urinary metal levels, biomarkers of metal exposure, and internal doses of metals impact CAC.

The researchers used data from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), which followed 6,418 men and women aged 45 to 84, from various ethnic backgrounds and free of clinical cardiovascular disease, to measure urinary metal levels at the start of the study between 2000 and 2002. They looked at nonessential (cadmium, tungsten, uranium) and essential (cobalt, copper, zinc) metals, both common in U.S. populations and associated with cardiovascular disease.

Pollution from cadmium, tungsten, uranium, cobalt, copper and zinc is widespread due to the use of these substances in agriculture and industry, such as fertilizers, batteries, oil production, welding, mining and nuclear power generation. Tobacco smoke is the main source of exposure to cadmium.

The results demonstrated that metal exposure may be associated with atherosclerosis over 10 years by increasing coronary calcification.

Comparing the highest to the lowest quartile of urinary cadmium, CAC levels were 51% higher at baseline and 75% higher over the 10-year period. For urinary tungsten, uranium, and cobalt, the corresponding CAC levels over the 10-year period were 45%, 39%, and 47% higher, respectively.

For copper and zinc, the corresponding estimates fell from 55% to 33% and from 85% to 57%, respectively, after adjusting for factors such as cardiovascular risk factors such as blood pressure and medications for hypertension, high cholesterol, and diabetes mellitus.

Urinary metal concentrations also varied by demographic characteristics. Higher urinary concentrations were observed in older participants, Chinese participants, and those with lower education levels. Los Angeles participants had significantly higher urinary concentrations of tungsten and uranium and slightly higher concentrations of cadmium, cobalt, and copper.

A previous paper on atherosclerosis (MESA) by the research team investigated the methodology for validating ultra-trace element concentrations in urine for small sample volumes in large epidemiological studies.

“We find small amounts of these metals everywhere, but this study really highlights that even low exposure affects cardiovascular health,” said Kathrin Schilling, Ph.D., assistant professor of environmental health sciences at Columbia Mailman School.

“Although we are making efforts to control exposure to metals in water, air and food, we need to pay more attention to analyzing toxic metals in populations to prevent and respond to exposures.”

“Pollution is the greatest environmental risk to cardiovascular health,” McGraw said. “Given the widespread presence of these metals from industrial and agricultural activities, this study calls for increased awareness and regulatory action to limit exposure and protect cardiovascular health.”

Limitations of the study include the unavailability of plate transition measurements in MESA, changes in exposure sources and other factors causing variability in some measured metals, and the potential for residual and unknown confounding from time-varying exposure measurements.

More information:

Urinary metal levels and coronary artery calcification: longitudinal data in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, Journal of the American College of Cardiology (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.jacc.2024.07.020

Provided by Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health

Quote:Metals in the body from pollutants linked to progression of harmful plaque buildup in arteries (2024, September 18) retrieved September 18, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.