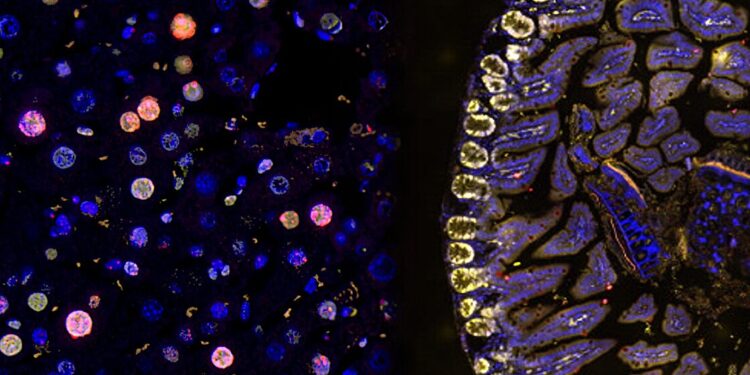

Liver cells with damaged DNA are stained red (left). Proliferating intestinal cells with undamaged DNA are stained yellow (right). Credit: UNIGE – UNIBE

The accumulation of mutations in DNA is often mentioned to explain the aging process, but it remains one hypothesis among others. A team from the University of Geneva (UNIGE), in collaboration with the Inselspital, the University Hospital of Bern and the University of Bern (UNIBE), has identified a mechanism that explains why certain organs, such as the liver, age more quickly than others.

The mechanism reveals that non-coding DNA damage, often hidden, accumulates more in slowly proliferating tissues, such as those of the liver or kidneys. Unlike organs that regenerate frequently, this damage remains undetected for a long time and prevents cell division. These results, published in the journal Cellopen new avenues for understanding cellular aging and potentially slowing it down.

Our organs and tissues do not all age at the same rate. Aging, marked by an increase in senescent cells, that is, cells that are unable to divide and have lost their functions, affects the liver or kidneys more quickly than the skin or intestine.

The mechanisms that contribute to this process are the subject of much debate within the scientific community. While it is widely accepted that damage to genetic material (DNA), which accumulates with age, is the cause of aging, the link between the two phenomena remains unclear.

DNA molecules contain coding regions – the genes that code for proteins – and non-coding regions that are involved in mechanisms that regulate or organize the genome. Constantly damaged by external and internal factors, the cell has DNA repair systems that prevent the accumulation of errors.

Errors in coding regions are detected during gene transcription, i.e. when genes are activated. Errors in non-coding regions are detected during cell renewal, which requires the creation of a new copy of the genome each time, via the process of DNA replication. However, cell renewal does not occur with the same frequency depending on the type of tissue or organ.

Tissues and organs in constant contact with the external environment, such as the skin or the intestine, renew their cells (and therefore replicate their DNA) more often – once or twice a week – than internal organs, such as the liver or kidneys, whose cells proliferate only a few times a year.

The liver, an ideal model for studying aging

The group of Thanos Halazonetis, full professor at the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology of the Faculty of Science of UNIGE, studies the mechanisms of DNA replication. His team, in collaboration with the groups of Professors Stroka and Candinas from the Inselspital of Bern and UNIBE, studied liver cells (hepatocytes), which proliferate infrequently. The scientists analyzed the potential link between the faster aging of the liver and the lower frequency of DNA replication in its cells.

“Our study model, the mouse liver, is an ideal organ to study DNA replication mechanisms in vivo. In adult mammals, hepatocytes rarely proliferate unless they have been partially ablated. By ablated two-thirds of the liver of young or old mice, we can study replication mechanisms in a young or aging organ, directly in the living organism,” explains Prof. Deborah Stroka, co-last author of the study.

By mapping for the first time the sites where DNA replication starts in liver cells that regenerate after ablation, the scientists discovered that these are always located in non-coding regions. They also observed that the initiation of replication was much more efficient in young mice than in old mice.

“These non-coding regions are not subject to regular error control and therefore accumulate damage over time. After liver removal in young mice, the damage is still low and DNA replication is possible. On the contrary, when the experiment is carried out in old mice, the excessive number of errors accumulated over time triggers an alarm system that prevents DNA replication,” explains Giacomo Rossetti, researcher at the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology of the Faculty of Science at UNIGE and first author of the study. This blockage of DNA replication prevents cells from proliferating, leading to a degradation of cellular functions and tissue senescence.

Hope to slow down the aging process

These observations may help explain why slowly proliferating tissues, such as the liver, age faster than rapidly proliferating ones, such as the intestine. In cells that have been dormant for long periods, too much cryptic DNA damage has accumulated in the noncoding regions, which contain the origins of replication, and prevents replication from starting. In rapidly proliferating tissues, by contrast, little damage accumulates because of frequent cell turnover, and the origins of replication remain effective.

“Our model suggests that by repairing cryptic DNA damage before replication is triggered, some aspects of aging could perhaps be prevented. This is the new working hypothesis on which our efforts will focus,” Halazonetis concludes.

More information:

In vivo DNA replication dynamics reveal aging-dependent replication stress, Cell (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.08.034. www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(24)00963-2

Cell

Provided by the University of Geneva

Quote:Why Some Organs Age Faster Than Others: Scientists Discover Hidden Mutations in Noncoding DNA (2024, September 17) Retrieved September 17, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.