Credit: Pixabay/CC0 Public Domain

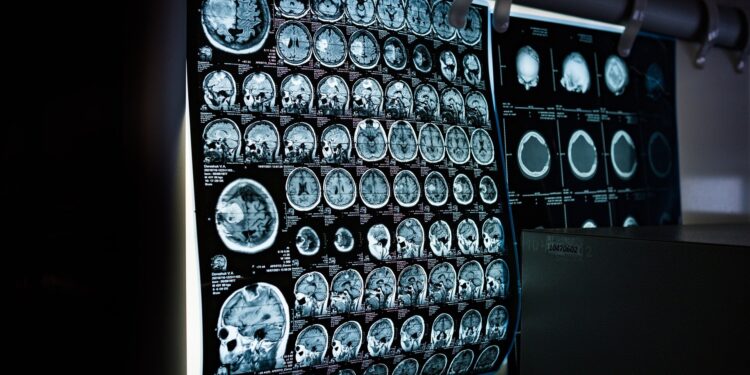

When surgeons perform brain surgery on people with brain tumors or epilepsy, they must remove the tumor or abnormal tissue while preserving the parts of the brain that control language and movement.

A new study from Northwestern Medicine could help doctors make better decisions about which areas of the brain to preserve, improving language function in patients after brain surgery. The study expands understanding of how language is encoded in the brain and identifies key features of critical sites in the cerebral cortex that work together to produce language.

If we think of the brain’s language network as a social network, scientists have actually identified the person who connects many subnets of people. Without that one person, they wouldn’t know each other. In the brain, these “connectors” perform the same function for language. If the connection sites were removed, the patient would make more language errors after surgery, such as difficulty naming objects, because the subnets wouldn’t be able to work together.

The study was published on September 16 in Nature Communications.

Brain signals from patients with brain tumors and epilepsy

Northwestern scientists identified critical language connection sites by recording electrical signals from the cerebral cortex of patients with epilepsy or brain tumors while they read words aloud. The researchers then analyzed the signals using graph theory and machine learning methods to predict which sites in the network were critical.

“This finding could help us be more accurate and efficient when mapping language sites before surgery,” said corresponding author Dr. Marc Slutzky, professor of neurology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and a neurologist at Northwestern Medicine.

“This could help us improve the way surgeons perform this mapping, which could potentially reduce the time it takes to stimulate or possibly eliminate stimulation and just record the electrical signals.”

People with brain tumors or epilepsy who need surgery often undergo functional mapping using direct electrical stimulation of the brain to try to identify critical parts of the brain (particularly in the cerebral cortex), so that neurosurgeons know which parts to avoid removing to preserve language. For example, electrical stimulation can temporarily interrupt the ability to speak or to conceive of names for objects, suggesting that the area to which the stimulation was applied is important for speech or language function.

Current stimulation technique has limitations

“The way this happens hasn’t changed much in over 50 years, but it’s still not clear what’s happening during this stimulation,” Slutzky said. “It’s not clear what’s special about the focal sites that the stimulation identifies as critical to language and speech.”

“When a person speaks, many areas of the brain are active, but only a handful of them are identified as essential for these functions by being disrupted during stimulation. Answering this question could help us understand how electrical stimulation affects the brain and how the brain produces spoken language.”

An estimated 1.2 million people in the United States are living with brain tumors.

Currently, many brain tumor patients undergo 20 to 60 minutes of stimulation while awake in the operating room. The technique is not perfect for identifying speech sites: results can be false negative or false positive, and the process can cause seizures.

“It’s not fun for the patient,” Slutzky said. “When we do it for epilepsy patients, the mapping can take a day or sometimes two and it’s exhausting for them.”

Epilepsy patients may need brain surgery when medications fail to adequately control seizures, Slutzky said.

How the study worked

The scientists recorded electrical signals from the surface of the cortex in 16 patients (at Northwestern Memorial Hospital and Johns Hopkins Hospital) with epilepsy or brain tumors. The electrode arrays were implanted in people with epilepsy as part of seizure monitoring before surgery or temporarily placed on the brain in the operating room while the tumor patients underwent awake brain surgery and mapping.

The patients read single words aloud on a monitor while researchers recorded their brain signals (called electrocorticography). The scientists then analyzed the signals using measures from graph theory, a branch of mathematics that focuses on networks. (Graph theory is also used to analyze all sorts of networks, including social networks, which are what many Internet search engines run on.)

These network measures describe how functionally connected each site is, whether locally (with neighboring sites), globally (with all recorded sites), or across communities (subnetworks). The scientists then used machine learning to predict which sites in the network were critical using only the network measures. Critical sites tended to be those that were connected across communities.

The Northwestern research is a collaboration between Nathan Crone and Yujing Wang of Johns Hopkins University (Department of Neurology) and Richard Betzel of Indiana University (Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences).

More information:

Nature Communications (2024).

Provided by Northwestern University

Quote:Scientists discover key features of language sites that could help preserve function after brain surgery (2024, September 16) retrieved September 16, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.