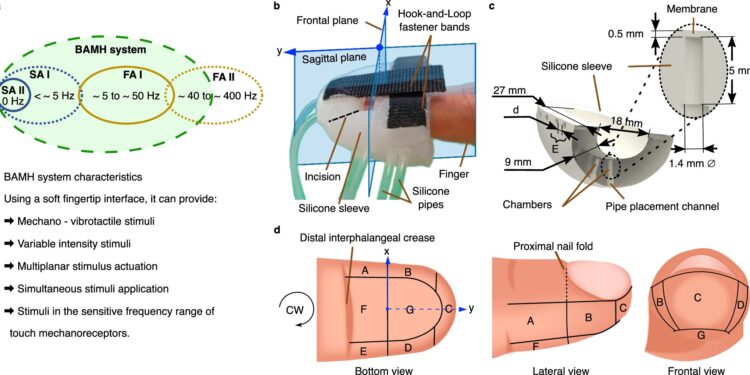

Fingertip haptic interface. Credit: Nature Communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-51779-8

A fingertip device that closely mimics the sensation of interacting with real objects, developed by a team led by UCL researchers, opens the way to applications in touch loss diagnosis, video calling, robotic surgery and hazardous waste management.

The study, published in Nature Communicationsdescribes the development of new touch technology, which can provide realistic feedback to the human fingertip to simulate touch more naturally than previous devices.

The more realistic design of this technology means it will help to better understand the complexities of our sense of touch, with a wide range of applications already envisaged.

One potential application of this technology is to improve the diagnosis of patients with sensory loss. Currently, diagnosis is made by a clinician touching the skin with single-fiber brushes of increasing weight and asking the patient if they can feel it, which gives an indication of the location of the sensory loss and its intensity.

The bioinspired haptic system (BAMH) could be used to automate this process, speeding it up, freeing up clinicians’ time and providing more empirical data on which to base diagnoses.

Professor Helge Wurdemann, author of the study and member of UCL’s Department of Mechanical Engineering, said: “The BAMH system improves our ability to quantify both sensitivity (the minimum stimulus intensity required for humans to perceive touch) and stimulus differentiation in human fingers. By reducing the subjectivity of current diagnostic methods, we believe the system can significantly improve this process.”

The team has obtained ethical approval to conduct a clinical trial to test this application, which is currently being set up. Another potential application of the technology is improving robotic surgery techniques.

Dr Sara Abad, lead author of the study and a member of UCL’s Department of Mechanical Engineering, said: “Surgeons can feel the difference between cancerous and normal tissue with their hands, for example, which helps them define the margins of a tumour before removing it. But if they are performing an operation using robotic arms, whether in the theatre or remotely, this tactile ability is lost.”

“We believe the BAMH system can restore some of this sensation, and we hope to conduct clinical trials to test this theory in the near future.”

The complexity of human tactile perception has long been a barrier to the development of effective tactile devices, often resulting in systems that struggle to provide intuitive and realistic feedback. The BAMH system, inspired by the workings of human perception, addresses these challenges by stimulating the four main types of tactile receptors in human skin.

According to Professor Wurdemann, “the human sense of touch involves sensations picked up by four types of receptors, present in different proportions in different areas of the fingertip. Some are better at detecting edges, for example, while others are better at interpreting texture. When we touch objects, we receive a complex mix of stimuli that help us perceive them accurately.”

“The system we developed can produce static and pulsed stimuli at different locations on the fingertip, with intensity levels that can be below or above the human sensitivity threshold. Importantly, these stimuli are delivered in a frequency range that matches the sensitivity of the skin’s touch receptors, enabling a tactile experience that closely mimics the sensation of interacting with real objects in everyday life.”

The impulses delivered by the BAHM system are in the sensitivity range of 0 to 130 Hertz of the tactile receptors of the skin. This allows for more precise activation of the tactile receptors on the front, lower and lateral areas of the finger, resulting in a more precise and selective sensation.

The study also found that the sensitivity of human finger stimuli varies across different areas of the fingertip and across different frequencies, highlighting the importance of delivering the right type of stimulus to each area of the finger to achieve a more realistic and accurate experience.

Dr Abad said: “Existing tactile feedback systems often require users to undergo training to be able to correctly interpret the stimuli they feel, partly because the range of sensations that existing systems can deliver is limited and also because of the rigidity of these systems. This challenge led us to ask: how can we stimulate the skin in a way that can enable more natural tactile feedback, thereby reducing the need for extensive user training?”

“To address this problem, we took a bio-inspired approach, focusing on how our perception of features such as object edges, textures, and skin elasticity depends heavily on the four main types of receptors found in our skin. The resulting technology offers a way to integrate touch into our virtual social interactions and can also serve as a diagnostic tool for tactile perception for patients who suffer from sensory loss.”

On Saturday 14 September, Professor Wurdemann and Dr Abad Guaman will present their innovation at the British Science Festival at the University of East London. Festival attendees will have the opportunity to experience first-hand how the technology simulates real-world sensations on their forearms, showing how digital and real-world connections can come closer together.

More information:

Sara-Adela Abad et al, Bioinspired adaptable multiplanar mechano-vibrotactile haptic system, Nature Communications (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-024-51779-8

Provided by University College London

Quote:Fingertip device enables realistic touch for wide range of applications (2024, September 13) retrieved September 13, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.