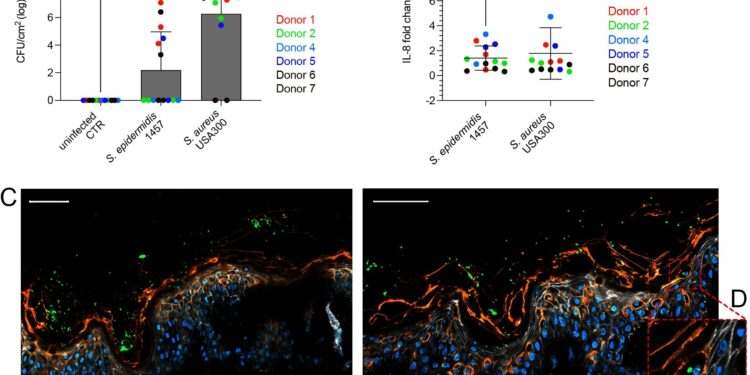

Tissue resident cells differentiate S. aureus from S. epidermidis via IL-1β following disruption of the healthy human skin barrier. Credit: PLOS Pathogens (2024). DOI: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1012056

In a study recently published in PLoS PathogensResearchers at AIMES, the Center for the Advancement of Integrated Medical and Engineering Sciences at Karolinska Institutet, have identified one of the subtle but effective pathways by which human skin differentiates between commensals and pathogens. Understanding these mechanisms opens the door to new targets for treatment and prevention, including ways to enhance innate immunity to prevent antibiotic-resistant infections.

“This shows how human skin differentiates between its commensal microbiota and potentially pathogenic bacteria that cause skin and soft tissue infections,” says Keira Melican, associate professor at AIMES, Department of Neuroscience and corresponding author of the paper.

“One of the challenges in infection research is understanding how our bodies recognize beneficial microbiota versus bacteria that pose a threat. The researchers studied how human skin responded to colonization by the common commensal bacterium Staphylococcus epidermidis compared to methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), a clinically important bacterium,” Melican continues.

“We identified a specific inflammatory signature when skin was exposed to MRSA. This signal could be linked to tissue-resident immune cells, Langerhans cells,” explains Julia C. Lang, postdoctoral researcher at AIMES and first author of the article.

Increasing antimicrobial resistance (AMR) means that bacterial infections are becoming harder to treat effectively. MRSA is the leading cause of AMR-related deaths in developed countries and new prevention and treatment options are needed.

New prevention and new treatments

This study was conducted using in vitro human skin models and cell cultures to investigate the interaction between host and bacteria in the human skin environment.

Immunotherapy and probiotics have been proposed as potential methods to prevent and treat skin infections, and this study addresses both aspects of the human skin environment. One of the drawbacks of previous research on skin infections has been the reliance on mouse models. It is becoming clear that mouse skin differs significantly from human skin, not only in its structure, but also in its immune response to bacteria.

Understanding how human skin differentiates commensals from pathogens and which skin cells mediate this differentiation will be essential for the continued development of new treatments.

“We want to better understand signaling pathways in human skin, using single-cell sequencing and spatial transcriptomics in the core facilities at Karolinska Institutet,” says Melican.

From a bacterial perspective, researchers focus on the aspects of bacteria that skin cells detect when differentiating commensal bacteria from pathogens.

More information:

Julia C. Lang et al, Tissue resident cells differentiate S. aureus from S. epidermidis via IL-1β following skin barrier disruption in healthy human skin, PLOS Pathogens (2024). DOI: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1012056

Provided by the Karolinska Institute

Quote:How human skin differentiates friendly bacteria from enemy bacteria (2024, September 3) retrieved September 3, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.