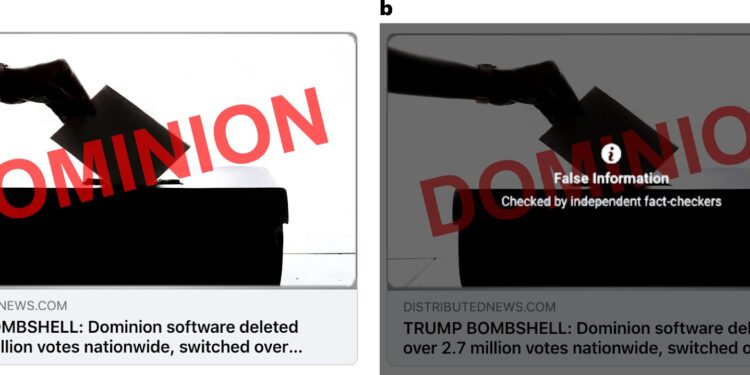

Experimental stimuli. Credit: Nature Human Behavior (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41562-024-01973-x

Do you trust fact-checkers? It may not matter. A new Nature Human Behavior A paper by MIT Sloan School of Management doctoral candidate Cameron Martel and professor David Rand reveals a surprising truth: Social media fact-checker warning labels can significantly reduce the belief and spread of misinformation, even among those who harbor doubts about the fact-checkers themselves.

Rumors and falsehoods can spread quickly on social media, making it difficult for users to distinguish fact from fiction. In response, most major platforms partner with third-party fact-checking organizations and attach warning labels to content deemed false or misleading, an approach that Martel and Rand’s previous research shows works on average.

However, trust in fact-checkers is not universal or uniform across political parties, and neither is exposure to misinformation. In the United States, research has shown that political conservatives are more likely to see and share misinformation and less likely to trust fact-checkers, raising concerns that these interventions could backfire.

“Most people don’t see a lot of misinformation,” Martel says. “And if people who are more likely to be exposed to misinformation are less likely to trust fact-checkers, it’s important to understand whether warning labels are effective for this group.”

Measuring Distrust in Fact-Checkers

To answer these questions, Martel and Rand used a two-part approach. First, they conducted a correlational study to validate a measure of trust in fact-checkers and identify correlates of distrust.

Consistent with previous studies, the researchers found that Republican-leaning survey participants were less likely to trust fact-checkers, whether they were right-wing or left-leaning. They also found that other characteristics significantly interacted with respondents’ political affiliations to shape their attitudes.

Republican respondents who knew more about news production, scored higher on a cognitive reasoning test, and had better web-using skills trusted fact-checkers even less. These factors did not predict differences among Democratic respondents. However, greater self-reported digital media literacy was correlated with greater trust in fact-checkers, regardless of political affiliation.

Attitudes versus actual responses

Martel and Rand then conducted a series of experiments with more than 14,000 participants in the United States to test the impact of media warnings on reactions to false headlines. Participants were exposed to a mix of politically balanced headlines, both true and false. Participants saw most of the false headlines accompanied by warnings similar to those used by Facebook, or no warning at all. Participants then rated the accuracy of each headline or indicated their willingness to share it.

While warning labels were somewhat more effective for people who scored high on trust in fact-checkers, they also consistently and significantly reduced belief in and willingness to share fake news among participants who showed distrust in fact-checkers. This was true even among participants who scored in the bottom quartile on trust in fact-checkers.

“Misinformation warning labels worked even for respondents in our sample who trusted fact-checkers the least and were the most politically right-wing — and we found no backlash,” Rand said. “This research builds on our existing work demonstrating the effectiveness of warning labels and reassures us that their effects are not one-sided.”

So what explains the gap between users’ attitudes toward fact-checkers and their response to warning labels?

Martel and Rand offer several possible explanations. Labels could prompt more critical evaluation of headlines, or individuals could refrain from sharing or expressing opinions about headlines labeled as false because of the risk of reputational damage. It’s also possible that politically engaged Republicans are more likely to express distrust of fact-checkers because they’ve been prompted to do so, rather than because of any deeply held belief.

Whatever the reason, Martel says, the research findings are good news for those concerned about the spread of misinformation.

“Labels aren’t perfect,” he noted. “It’s important that platforms also have other options, like demotion or removal, for potentially more harmful content. However, this work shows that content warnings are a useful tool that can work for a wide range of people, even if they say they don’t trust them.”

More information:

Cameron Martel et al, Fact-checker warning labels are effective even for those who distrust fact-checkers, Nature Human Behavior (2024). DOI: 10.1038/s41562-024-01973-x

Provided by MIT Sloan School of Management

Quote:Fact-checker warning labels work, even if you don’t trust them, study finds (2024, September 3) retrieved September 3, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.