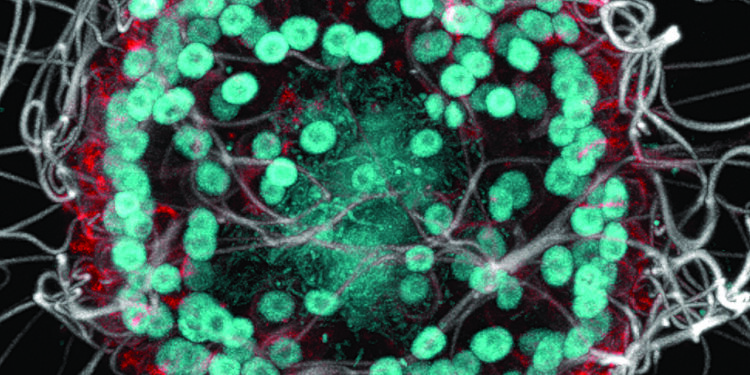

A choanoflagellate colony stained to show its features. Cyan indicates DNA (the doughnut-shaped DNA of the choanoflagellate cells and a cloud of bacterial DNA inside the colony), while flagella are white and the microscopic hairs (villi) on each cell are red. Credit: Kayley Hake, Nicole King’s lab, UC Berkeley

Mono Lake in the eastern Sierra Nevada is known for its towering tufa formations, abundant brine shrimp and black clouds of alkali flies that are particularly adapted to the salty water, which is laden with arsenic and cyanide.

Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, have discovered another unusual creature lurking in the shallow, salty waters of the lake, one that could tell scientists about the origins of animals more than 650 million years ago.

The organism is a choanoflagellate, a microscopic single-celled life form that can divide and grow into multicellular colonies in a manner similar to the formation of animal embryos. It is not, however, a type of animal, but a member of a sister group to all animals. And as the closest living relative of animals, the choanoflagellate is a crucial model for the transition from single-celled to multicellular life.

Surprisingly, it harbors its own microbiome, making it the first known choanoflagellate to establish a stable physical relationship with bacteria, rather than just eating them. As such, it is one of the simplest organisms known to have a microbiome.

“Very little is known about choanoflagellates, and there are interesting biological phenomena that we can only understand if we understand their ecology,” said Nicole King, a professor of molecular and cellular biology at UC Berkeley and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute (HHMI) investigator who studies choanoflagellates as a model of what primitive life looked like in ancient oceans.

Typically visible only under a microscope, choanoflagellates are often overlooked by aquatic biologists, who instead focus on macroscopic animals, photosynthetic algae or bacteria. Yet their biology and lifestyles can provide insight into the creatures that existed in the oceans before animals evolved and that eventually gave rise to animals. This species in particular could shed light on the origin of the interactions between animals and bacteria that led to the human microbiome.

“Animals evolved in oceans filled with bacteria,” King says. “If you think of the tree of life, all the organisms alive today are related to each other through evolution. So if we study the organisms alive today, we can piece together what happened in the past.”

King and colleagues at the University of California, Berkeley, described the organism, which they named Barroeca monosierra after the lake, in a paper published Aug. 14 in the journal mBio.

A beautiful colony

Nearly 10 years ago, Daniel Richter, then a graduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, returned from a rock-climbing hike in the eastern Sierra Nevada with a vial of Mono Lake water he had randomly collected along the way. Under the microscope, it was teeming with choanoflagellates. Aside from brine shrimp, alkali flies, and various species of nematodes, little other life has been reported in the lake’s inhospitable waters.

“There were a lot of these big, beautiful colonies of choanoflagellates,” King said. “I mean, they were the biggest we’ve ever seen.”

Colonies of what appeared to be nearly 100 identical choanoflagellate cells formed a hollow sphere that rotated and spun as each individual cell kicked its flagella.

Globular colonies of the choanoflagellate B. monosierra observed under a microscope. As indicated by the 50-micron scale bar, these colonies are at the limit of what is visible to the naked eye. Credit: Alain Garcia De Las Bayonas, Nicole King Laboratory

“One of the interesting features of these colonies is that they are similar in shape to the blastula, a hollow ball of cells that forms early in animal development,” King said. “We wanted to learn more about that.”

At the time, King was caring for other species of choanos, as she calls them, and so the Mono Lake choanos languished in the freezer until students revived them and stained them to observe their unusual doughnut-shaped chromosomes. Surprisingly, there was also DNA inside the hollow colony where there should have been no cells. After further investigation, graduate student Kayley Hake determined that they were bacteria.

“The bacteria were a huge surprise. It was just fascinating,” King said.

Hake also detected connective structures, called extracellular matrix, inside the spherical colony that were secreted by the choanos.

It was only then that it occurred to Hake and King that perhaps these were not the remains of bacteria eaten by the choanos, but bacteria living and grazing on substances secreted by the colony.

“No one had ever described a choanoflagellate having a stable physical interaction with bacteria,” she said. “In our previous studies, we found that choanos responded to small bacterial molecules floating in the water, or that choanos ate the bacteria, but there was no case where they were doing anything that could potentially be a symbiosis. Or in this case, a microbiome.”

3D reconstruction of a spherical colony of 70 choanoflagellates of the newly named species Barroeca monosierra discovered in Mono Lake. Colonies of these organisms consist of many identical cells (cyan), each with flagella (orange) that allow them to propel themselves through the water. This choanoflagellate colony harbors its own microbiome, a phenomenon never before observed in these organisms. Credit: Davis Laundon and Pawel Burkhardt, Sars Centre, Norway; Kent McDonald and Nicole King, UC Berkeley

King teamed up with Jill Banfield, a metagenomics pioneer and professor of environmental science, policy and management, and Earth and planetary sciences at the University of California, Berkeley, to determine which bacterial species were in the water and inside the choanos. Metagenomics involves sequencing all the DNA in an environmental sample to reconstruct the genomes of the organisms living there.

After Banfield’s lab identified the microbes in the Mono Lake water, Hake created DNA probes to determine which ones were also inside the choanoflagellates. The bacterial populations weren’t identical, King said, so clearly some bacteria survived better than others inside the oxygen-deprived lumen of the choanoflagellate colony. Hake determined that they weren’t there by accident; they were growing and dividing. Perhaps they were escaping the lake’s toxic environment, King mused, or perhaps the choanoflagellates were breeding the bacteria to eat them.

She admits that this is all speculation. Future experiments should uncover how bacteria interact with choanoflagellates. Previous work in her lab has shown that bacteria act as an aphrodisiac to stimulate mating in choanoflagellates, and that bacteria can stimulate single-celled choanos to aggregate into colonies.

For her, the choanoflagellates of Mono Lake will become another model system for studying evolution, just like the choanos that live in the pools of water on the Caribbean island of Curaçao—her main focus at the moment—and the choanos from the pools of the North and South Poles. Getting more samples from Mono Lake, however, may be difficult. On a recent visit, only six of 100 samples contained these energetic microorganisms.

“I think there’s a lot more to be done on the microbial life in Mono Lake, because it’s the foundation of everything else in the ecosystem,” King said. “I’m excited about B. monosierra as a new model for studying interactions between eukaryotes and bacteria. And I hope it can teach us something about evolution. But even if it doesn’t, I think it’s a fascinating phenomenon.”

In addition to King, Banfield, Hake and Richter, co-authors of the UC Berkeley paper include former doctoral student Patrick West, electron microscopist Kent McDonald and postdoctoral researchers Josean Reyes-Rivera and Alain Garcia De Las Bayonas.

More information:

KH Hake et al, A large colonial choanoflagellate from Mono Lake harbors live bacteria, mBio (2024). DOI: 10.1128/mbio.01623-24

Journal information:

mBio

Provided by University of California – Berkeley

Quote: A creature the size of a speck of dust has been discovered hiding in Mono Lake in California (2024, August 22) retrieved August 22, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.