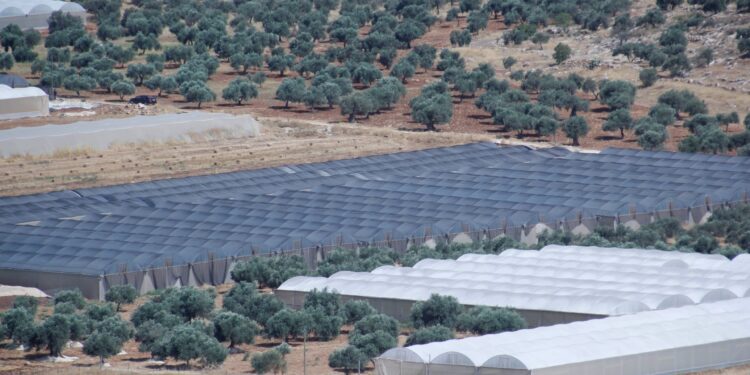

NablusFrom a barren land that was barely planted with a little wheat annually, the western plain in the village of Beit Dajan near the city of Nablus in the northern West Bank has become a green paradise, after its owners filled it with dozens of plastic houses and planted them with various types of vegetables in a step that revived the town’s economy and challenged the difficult living conditions they have been suffering from for ten months.

In a collective initiative, more than 70 “Israeli workers” in Beit Dajan decided to reclaim and cultivate their lands, in order to completely dispense with the Israeli occupation, which has prevented them from reaching their workplaces since October 7, 2023.

With support provided by the Agricultural Relief (unofficial) through paving roads and extending the water network, and with the village council providing infrastructure services such as electricity and others, the agricultural project was launched in the village more than two months ago and began to produce its products.

Like the other 200+ “Israeli workers” in the village of Beit Dajan, Mazen Abu Jish, a 40-year-old man, lost his job after 12 years in Israel and remained unemployed until last March, when he and dozens of others like him took the initiative to reclaim their lands in the western plain.

Land is better than “Israeli slavery”

From 150 dunams (one dunam equals one thousand square meters), Abu Jish cultivated one and a half dunams of land, and planted it with tomatoes and green peppers. It produced a plentiful crop that generated a good income in light of difficult economic conditions and unemployment that exceeded 32% in the West Bank and approached 80% in Gaza, according to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics.

Al Jazeera Net toured the targeted area in the village of Beit Dajan, and closely examined this experience, which emerged as the first collective initiative from which “Israeli workers” benefited, and created an alternative that saved them effort and time, and most importantly, as Abu Jish says, “their return to their land and establishing its identity away from the slavery of labor in Israel.”

Abu Jish added to Al Jazeera Net that “the financial compensation in Israel may be somewhat better, but the work there is exhausting and without dignity.”

In the language of numbers, Abu Jish describes his new project and says that it is better than working in Israel. For every 6 hours of work on the land, it is equivalent to 17 hours in Israel. In addition, he works freely, safely, quietly, with psychological comfort and belonging. Preserving the land is more important than economic feasibility.

From a simple income of no more than 200 US dollars for the production of one dunum of wheat annually, the same area has become profitable many times over after cultivation inside plastic greenhouses, and at an amount exceeding 8 thousand US dollars annually according to Abu Jish, because it is sustainable cultivation throughout the year and its economic feasibility is more effective.

Abu Jish works on his farm with two of his sons, and like the rest of the farmers, he is working to employ other “Israeli workers.” He is also working to develop his crops with new varieties of vegetables and fruits, such as grapes and strawberries.

Land reclamation and protection from settlement

Since the war on Gaza 9 months ago, Israel has closed its ports and crossings in the face of 200,000 Palestinian workers, causing a loss of 1.25 billion shekels per month (about 342 million dollars), according to the General Federation of Palestinian Workers’ Unions.

Like Abu Jish, citizen Samir Jamil Hamed chose to return to his land and farm it after he had reclaimed it and obtained basic agricultural services, most importantly water. He says that ten years of working in Israel had exhausted him and did not give him the joy he now experiences on his land.

By paying part and installments of the price of the greenhouse, estimated at 10 thousand US dollars, Hamed reclaimed his land and planted it with cucumbers and tomatoes, and he spares no effort in developing his farm, improving its production and increasing it.

Hamed and farmers like him aim to increase the number of reclaimed dunams to reach 300 dunams by the coming year 2025. This is of course in addition to improving the economy of their village and employing its people to protect their land from confiscation and settlement, especially since the occupation classifies it as “C” areas and subjects it to its security and administrative control, which has prompted many citizens to rent fallow lands from their owners and cultivate them.

Amidst a huge turnout… what do supporters say?

The idea of agricultural relief is basically based on converting rainfed agriculture in the Beit Dajan plain to irrigated agriculture. This coincided with the cessation of work in Israel, so dozens of workers from the village resorted to benefiting from the project, which now employs 300 workers daily, according to the Director General of Agricultural Relief, Munjed Abu Jish.

Munjed Abu Jish added in an interview with Al Jazeera Net that they are in the process of expanding the initiative to include other crops, especially since the water network has become available and now covers about 5,000 dunams of plain land extending between the villages of Beit Dajan and Beit Furik, which have a population of more than 20,000 people.

He says, “Agriculture of all kinds will meet the local needs of these two towns besieged behind a military checkpoint (Beit Furik checkpoint) that controls their fate.”

To develop such initiatives and projects and facilitate the means for citizens, Agricultural Relief provides support directly to farmers, and prepares the infrastructure of water networks, roads, etc., in addition to supporting specific agricultural models to make them successful, and working with all energy to market the product, which is the major dilemma facing farmers.

There are approximate data that say that a large part of the “Israeli workers” and workers in general turned to the agricultural sector after the Al-Aqsa flood, considering it the “closest option” for them, according to Munajed Abu Jish, who added that the demand for agriculture increased by 30% after the war compared to what it was before that, pointing out that more than 7,000 plastic houses were built.

For his part, the Director of the Olive Department at the Ministry of Agriculture, Ramez Obeid, says that they have indicators of an increase in the agricultural area in the West Bank, and people’s greater interest in it.

He added that they have seen this through the Greening Palestine project, in which they distribute half a million trees annually. He explained that demand has increased through the various agricultural directorates, as has demand for plastic greenhouses.