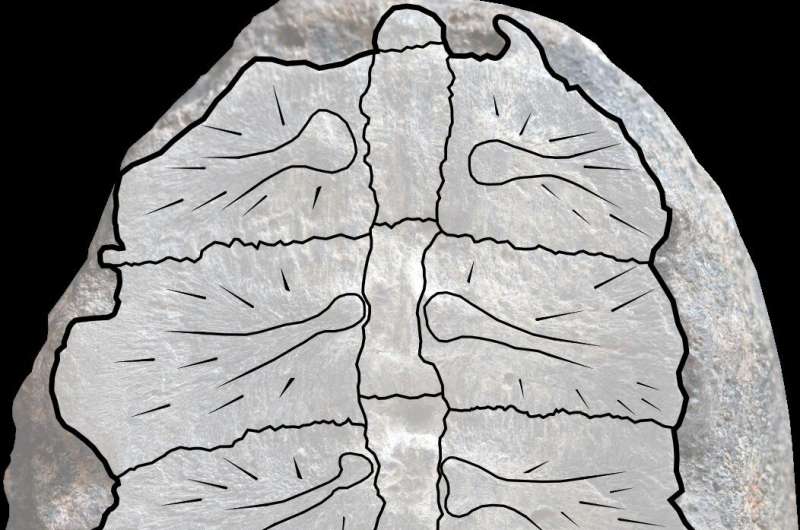

The fossil that was originally interpreted to be a plant, but which researchers have now discovered, is the inside of the shell of a baby turtle. . Credit: Photo by Fabiany Herrera and Héctor Palma-Castro.

From the 1950s to the 1970s, a Colombian priest named Padre Gustavo Huertas collected rocks and fossils near a town called Villa de Levya. Two of the specimens he found were small, round rocks decorated with lines that resembled leaves; he classified them as a type of fossil plant. But in a new study published in the journal Electronic paleontologyresearchers re-examined these “plant” fossils and discovered that they weren’t plants at all: they were the fossilized remains of baby turtles.

“It was really surprising to find these fossils,” says Héctor Palma-Castro, a paleobotany student at the National University of Colombia.

The plants in question were described by Huertas in 2003 under the name Sphenophyllum colombianum. The fossils come from rocks from the Lower Cretaceous, between 132 and 113 million years ago, during the time of the dinosaurs. The fossils of Sphenophyllum colombianum were surprising at that time and place: the other known members of the genus Sphenophyllum became extinct more than 100 million years ago. The age and location of the plants piqued the interest of Fabiany Herrera, Negaunee assistant curator of fossil plants at the Field Museum in Chicago, and her student, Palma-Castro.

“We went to the fossil collection at the National University of Colombia in Bogotá and started looking at the plants. As soon as we photographed them, we thought, ‘This is weird,'” says Herrera, who collects plants from the Lower Cretaceous. from northwestern South America, a region of the world with little paleobotanical work.

At first glance, the fossils, about 2 inches in diameter, looked like rounded nodules containing the preserved leaves of the Sphenophyllum plant. But Herrera and Palma-Castro noticed key elements that weren’t quite right.

“We spent days looking for plant fossils in wooden cabinets. When we finally found this fossil, deciphering the shape and edge of the leaf proved a challenge,” says Palma-Castro.

“When you look at them in detail, the lines visible on the fossils don’t look like the veins of a plant. I was sure that they were most likely bones,” says Herrera. He therefore contacted one of his former colleagues, Edwin-Alberto Cadena.

“They sent me the photos and I said, ‘That really looks like a carapace,’ the bony upper shell of a turtle,” says Cadena, a paleontologist specializing in turtles and other vertebrates at the Universidad del Rosario of Bogota. When he saw the scale of the photos, Cadena recalls, “I said, ‘Well, that’s remarkable, because it’s not only a turtle, but it’s also a newborn specimen , he’s very, very small.'”

Drawing highlighting the ribs and back bones, superimposed on the fossil. Credits: Fabiany Herrera and Héctor Palma-Castro; drawing by Edwin-Alberto Cadena and Diego Cómbita-Romero.

Cadena and his student, Diego Cómbita-Romero of the National University of Colombia, examined the specimens in more detail, comparing them with fossil and modern turtle shells.

“When we first saw the specimen, I was amazed, because the fossil did not have the typical markings on the outside of a turtle’s shell,” says Cómbita-Romero. “It was a bit concave, like a bowl. At that point we realized that the visible part of the fossil was the other side of the shell, we were looking at the part of the shell that is inside of the turtle.”

Details of the turtle’s bones helped researchers estimate its age at the time of its death. “Growth rates and sizes of turtles vary,” says Cómbita-Romero. So the team looked at features like the thickness of its shell and where its ribs joined together to form strong bones.

“This is a rare feature in hatchlings but seen in juveniles. All of this information suggests that the turtle likely died with a slightly developed shell, between 0 and 1 year of age, in the post-hatch stage,” he said.

“In general, it is very rare to find fossil turtle hatchlings,” Cadena explains. “When turtles are very young, their shell bones are very thin and can therefore be easily destroyed.”

Researchers say the rarity of fossilized baby turtles makes their discovery significant. “These turtles were likely related to other Cretaceous species up to 15 feet long, but we don’t know much about how they actually reached such giant sizes,” says Cadena.

The researchers don’t blame Padre Huertas for his mistake: the preserved shells actually resemble many fossil plants. But the features Huertas thought were leaves and stems are actually the modified ribs and vertebrae that make up a turtle’s shell. Cómbita-Romero and Palma-Castro nicknamed the specimens “Turtwig,” after a half-turtle, half-plant Pokémon.

“In the Pokémon universe, you encounter the concept of combining two or more elements, such as animals, machines, plants, etc. So when you have a fossil initially classified as a plant that turns out to be a baby turtle, a few Pokémon immediately come to mind. In this case, Turtwig, a baby turtle with a leaf attached to its head,” says Palma-Castro.

“In paleontology, your imagination and capacity for wonder are always tested. Discoveries like these are truly special because they not only expand our knowledge of the past, but also open a window into the diverse possibilities of what we can find out.”

Scientists also note the importance of these fossils within the broader framework of Colombian paleontology. “We have solved a small paleobotanical mystery, but more importantly, this study shows the need to re-study historical collections in Colombia. The Lower Cretaceous is a critical period in the evolution of land plants, particularly for flowering plants and gymnosperms. Our future work is to discover the forests that grew in this part of the world,” explains Herrera.

More information:

A Lower Cretaceous Sphenophyllum or a Newborn Turtle? Electronic paleontology (2023), DOI: 10.26879/1306

Quote: It turns out that this plant fossil is actually a baby turtle fossil (December 7, 2023) recovered on December 7, 2023 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.