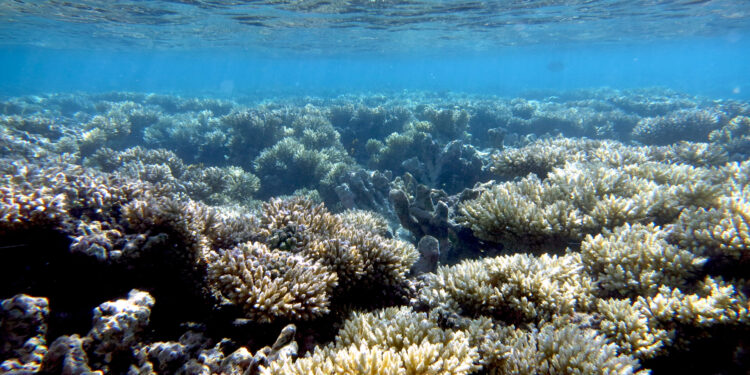

Acropora coral at the study site. Credit: Dr Cassandra Benkwitt

Tropical coral reefs are among our most spectacular ecosystems, but rapid global warming threatens the future survival of many reefs. However, there may be hope for some tropical reefs in the form of feathered friends.

A new study by researchers at Lancaster University has found that the presence of seabirds on islands adjacent to tropical coral reefs can double the growth rate of corals on these reefs.

And because of this faster growth, coral reefs near seabird colonies can recover much more quickly from bleaching events – which often cause mass coral die-offs when the sea becomes too warm – also found the international team of researchers.

The study focused on Acropora, an important type of coral that provides complex structures supporting fish populations and reef growth, and is also important for protecting coastal areas from waves and storms. The study results are presented in the article “Seabirds boost coral reef resilience” published in Scientists progress.

Researchers found that Acropora around seabird islands recovered from bleaching events about 10 months faster (about three years and eight months) than reefs away from seabird colonies (four years and six months).

Researchers say these shorter recovery times could be the difference between continuing to rebound for some reefs in the face of a warming planet where damaging bleaching events now occur much more frequently than in previous decades.

The key to how seabirds can help tropical coral reefs grow and recover more quickly is through their droppings. Seabirds feed on fish in the open ocean, far from the islands, then return to the islands to roost, depositing nutrients rich in nitrogen and phosphorus on the island in the form of guano. Some of the guano is washed away by rain and released into surrounding seas, where the nutrients fertilize corals and other marine life.

“Our results clearly show that seabird-derived nutrients directly lead to faster coral growth rates and faster recovery rates in Acropora corals,” said Dr. Casey Benkwitt, a coral reef ecology researcher at Lancaster University and lead author of the study.

“This faster recovery could be crucial since the average time between successive bleaching episodes was 5.9 years in 2016, a reduction from 27 years in the 1980s. Even small reductions in recovery times over the This window could be essential for maintaining coral cover in the short term. “she added.

The researchers’ study focused on an isolated archipelago in the Indian Ocean. They compared reefs near islands with thriving populations of seabirds, such as red-footed boobies, sooty terns and least noddies, to reefs near islands with few seabirds. . Islands where there are few birds are home to populations of rats, an invasive species that is very damaging and devastating to birds because they eat eggs and chicks. It’s no coincidence that islands with thriving bird populations are rat-free.

Reefs in the study area experienced significant coral bleaching and mortality following the 2015-2016 marine heatwaves, which made it possible to observe and compare how corals on different reefs recovered. restored. The researchers surveyed sites from one year before the bleaching event to six years after the bleaching, and modeled Acropora recovery for the years between surveys.

The research team sampled stable isotope values of nitrogen, a reliable tracer of seabird-derived nutrients, and measured growth rates of Acropora corals for three years.

Red-footed booby. Credit: Dr Cassandra Benkwitt

The results showed that seabird-derived nutrients absorbed by corals near the bird islands increased coral growth rates, with the rate doubling for every unit increase in seabird nutrients.

In contrast, corals near rat-infested islands had similar nutritional values to those found far from the islands, showing that the nutrient supply had been virtually cut off by the lack of birds.

The scientists also undertook an experimental approach to determine whether the faster growth was directly due to nutrients, as opposed to other factors such as genetic differences in corals between different islands. They transplanted Acropora corals between islands with and without rats.

This experiment confirmed that it was the presence of seabirds that caused the nutrient enrichment.

At the island level, coral colonies transplanted to seabird islands grew twice as fast as those transplanted to rat-infested islands. Natural coral colonies were also found to grow faster near rat-free islands, with an estimated growth rate 2.4 times faster than that of corals around rat-infested islands.

Dr Benkwitt said: “We were able to demonstrate a clear link between the presence of seabirds and faster coral growth. It’s really exciting and encouraging that a natural solution is available to help build the resilience of coral reefs to climate change. a warming planet.

Seabirds flying over an island without rats. Credit: Dr Cassandra Benkwitt

“By restoring seabird populations, corals can quickly absorb and benefit from new nutrients, and our three-year experience shows that these benefits are not just a brief boost: they can be sustained on the long term.”

The researchers say their findings add weight to the growing body of evidence that shows the ecological damage caused to terrestrial and marine ecosystems by invasive rats on tropical islands.

Professor Nick Graham from Lancaster University and lead researcher on the study said: “Combined, these results suggest that eradicating rats and restoring seabird populations could play an important role in recovery. natural flows of nutrients for seabirds to the coastal marine environment, thereby enhancing rapid recovery of coral reefs, which will be crucial as we expect to see more frequent climate disruptions. »

The environmental benefits of nutrients for seabirds go beyond increasing coral recovery rates. “Growth rates of fish on reefs adjacent to islands with large seabird colonies are also faster and overall fish biomass is 50% higher than on reefs adjacent to islands with rats,” said Dr Shaun Wilson, co-author of the study from the Australian Institute of Marine Science.

“As a result, rates of grazing and bioerosion by fish are three times faster on islands with seabirds, key processes helping to maintain a healthy reef.”

More information:

Cassandra Benkwitt et al, Seabirds strengthen the resilience of coral reefs, Scientists progress (2023). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adj0390. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adj0390

Provided by Lancaster University

Quote: Feathered friends may become unlikely helpers for tropical coral reefs facing the threat of climate change (December 6, 2023) retrieved December 7, 2023 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.