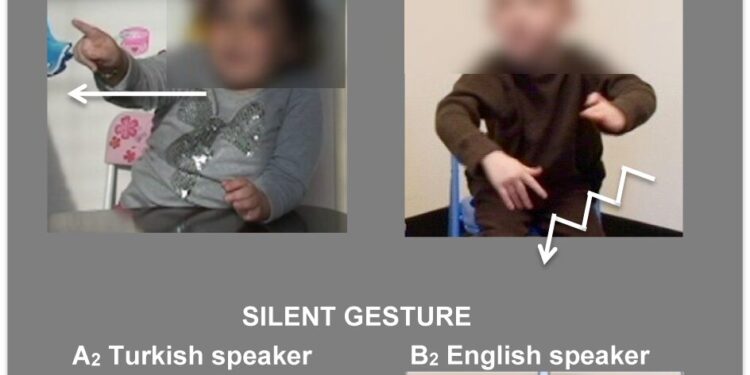

The three-dimensional stimulus scene depicting a girl’s running movement toward the house (top panel) and its gestural description by 3- to 4-year-old children learning Turkish or English. In the co-speech gesture, children learning English combine manner and path in a single gesture (quickly rotating both palms while moving them forward to convey forward stroke; B1); children learning Turkish only express a path without manner (by drawing a line with the right index finger from left to right transmitting a movement to the right; A1). In a silent gesture, child speakers of each language combine manner and path in a single gesture by walking the middle and index fingers from left to right (A2) or moving the right hand forward away from the speaker (B2). The jagged arrows indicate the movement of both manner and path; straight arrows indicate movement with only one path. Credit: Language and cognition (2023). DOI: 10.1017/langcog.2023.34

Recent research at Georgia State University shows that native language affects the way people transmit information from a young age and suggests the existence of a universal communication system.

Şeyda Özçalışkan, professor at the Department of Psychology, has been studying the connection between language and thought for years. His latest study, “What the development of gesture with and without speech can teach us about the effect of language on thought”, published in Language and cognitionis a continuation of previous work with adults.

For this study, Özçalışkan, in collaboration with Susan Goldin-Meadow of the University of Chicago and Che Lucero of Cornell University, focused on children ages 3 to 12. The children spoke English or Turkish. They were asked to use their hands to mime specific actions, such as running through a house.

“English and Turkish are the main comparisons because they differ in the way you talk about events,” said Özçalışkan, herself a native Turkish speaker.

“If you speak Turkish, if you want to describe someone running into a house, you have to break it down. You say, ‘He runs and then he runs into the house,'” she said. “But if it’s in English, they’ll just say ‘he ran into the house,’ all in one compact sentence. As such, it’s easier to express both running (manner of movement) and enter (movement path) together in one expression in English than in Turkish.

“We wanted to know whether or not gesture follows these differences and when children learn these patterns.”

The researchers asked the children to describe the same action first by speaking (speech and co-speech gesture) and then without speaking with only their hands (called silent gesture).

They found that when children spoke and gestured at the same time, their gestures followed the conventions of their language, with clear differences between the gestures of Turkish and English speakers. However, when the children used gestures without speaking, their gestures were remarkably similar.

“It is easier to express run and enter in one gesture than through speech, especially for Turkish speakers who have to express run and enter in two separate sentences in their speech,” Özçalışkan said. “So when you don’t speak, the gesture doesn’t need to follow the separation between manner and path, and you can easily put them together.”

The study also found that these tendencies manifest themselves at a very young age. Children’s co-speech gesture begins to follow the patterns of their spoken language around 3 to 4 years of age.

Özçalışkan, in collaboration with Goldin-Meadow, also studied sighted and blind adults. These participants also spoke English and Turkish. Using the same methods as in his last study, the researchers were surprised to find the same differences in co-speaking gestures and the same similarities in silent gestures. This was despite the fact that the blind participants were blind from birth, meaning they had never seen anyone make a gesture before.

So far, Özçalışkan said, all studies have produced very similar results. In fact, many of the gestures used by participants resemble what are called “household sign systems,” which are informal sign language systems created spontaneously by deaf children, who have not been exposed to conventional sign language by their hearing parents.

“What we actually see are some of these basic structures that we see, for example, in early sign languages,” Özçalışkan said.

This model suggests that there might be a universal gesture system that would allow us to communicate with each other, regardless of language, hearing ability, or sight.

Özçalışkan said the next step in this research would be to study Turkish and English-speaking blind children to see if the same patterns are present.

“We established in our previous work that blind adults gesture like sighted adults… They showed differences in speech and co-speech gestures, but when they don’t speak, they show similarities. So the next question is, at what age do we see evidence of this?’” Özçalışkan said.

More information:

Şeyda Özçalışkan et al, What the development of gesture with and without speech can teach us about the effect of language on thought, Language and cognition (2023). DOI: 10.1017/langcog.2023.34

Provided by Georgia State University

Quote: Study suggests the existence of a universal nonverbal communication system (December 5, 2023) retrieved December 6, 2023 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.