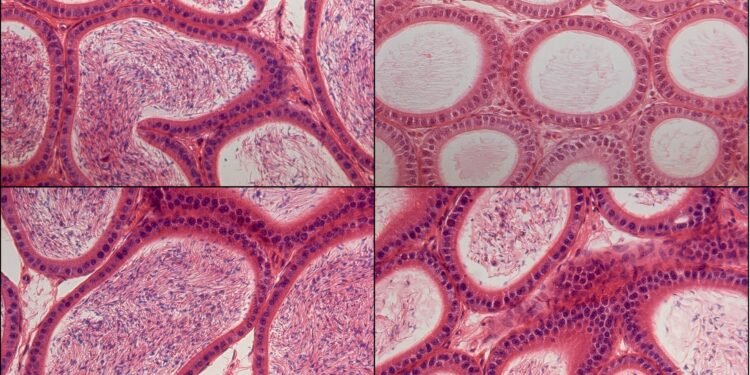

Sperm, shown inside each round cell, were not generated when the mice were taking the HDAC inhibitor drug (top right), but after 60 days of stopping the drug, spermatogenesis was recovered (bottom right). The left column shows sperm at the same time in a mouse that did not receive the drug. Credit: Salk Institute

Surveys show that most men in the United States want to use male contraceptives, but their options remain limited to unreliable condoms or invasive vasectomies. Recent attempts to develop drugs that block sperm production, maturation, or fertilization have had limited success, providing incomplete protection or serious side effects.

New approaches to male contraception are needed, but because sperm development is so complex, researchers have struggled to identify which parts of the process can be tinkered with safely and effectively.

Now, scientists at the Salk Institute have discovered a new, non-hormonal, reversible method for interrupting sperm production. The study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences implicates a novel protein complex in the regulation of gene expression during sperm production.

Researchers demonstrate that treating male mice with an existing class of drugs, called HDAC (histone deacetylase) inhibitors, can disrupt the function of this protein complex and block fertility without affecting libido.

“Most experimental male contraceptive drugs use a hammer approach to block sperm production, but ours is much more subtle,” says lead author Ronald Evans, professor, director of the Gene Expression Laboratory and chair March of Dimes in molecular and developmental biology in Salez. “This makes it a promising therapeutic approach, which we hope to see soon developed for human clinical trials.”

The human body produces several million new sperm per day. To do this, sperm stem cells in the testes continually produce more of themselves until a signal tells them it is time to develop into sperm, a process called spermatogenesis. This signal comes in the form of retinoic acid, a product of vitamin A. Pulses of retinoic acid bind to retinoic acid receptors in cells, and when the system is perfectly aligned, this triggers a program complex genetics that transform stem cells into stem cells. mature sperm.

Salk scientists discovered that for this to work, retinoic acid receptors must bind to a protein called SMRT (silent mediator of retinoid and thyroid hormone receptors). SMRT then recruits HDACs, and this protein complex then synchronizes the expression of genes that produce sperm.

Previous groups have attempted to stop sperm production by directly blocking retinoic acid or its receptor. But retinoic acid is important to several organ systems, so disrupting it throughout the body can cause a variety of side effects — a reason why many previous studies and trials have failed to produce a viable drug. Evans and his colleagues instead asked whether they could modulate one of the molecules downstream of retinoic acid to produce a more targeted effect.

The researchers first looked at a line of genetically modified mice previously grown in the laboratory, in which the SMRT protein was mutated and could no longer bind to retinoic acid receptors. Without this SMRT-retinoic acid receptor interaction, the mice were not able to produce mature sperm. However, they displayed normal testosterone levels and increasing behavior, indicating that their desire to mate was not affected.

To see if they could reproduce these genetic results with pharmacological intervention, the researchers treated normal mice with MS-275, an oral HDAC inhibitor with breakthrough status from the FDA. By blocking the activity of the SMRT-retinoic acid receptor-HDAC complex, the drug was able to stop sperm production without producing obvious side effects.

Another remarkable thing also happened once treatment was stopped: Within 60 days of stopping the pill, the animals’ fertility was completely restored and all subsequent offspring were developmentally healthy.

The authors say their strategy of inhibiting molecules downstream of retinoic acid is key to achieving this reversibility.

Think of retinoic acid and sperm-producing genes like two dancers in a waltz. Their rhythm and steps must be coordinated with each other for the dance to work. But if you add something that causes the genes to miss a step, the two are suddenly out of sync and the dance breaks down. In this case, the HDAC inhibitor causes the genes to misstep, stopping sperm production.

However, if the dancer manages to find his bearings and get back to the rhythm of his partner, the waltz can resume. Similarly, the authors claim that removing the HDAC inhibitor allows sperm-producing genes to re-synchronize with retinoic acid pulses, restarting sperm production as desired.

“It’s all about timing,” says co-author Michael Downes, a senior scientist in Evans’ lab. “When we add the drug, the stem cells are no longer in sync with the pulses of the retinoic acid and sperm production is interrupted. But as soon as we remove the drug, the stem cells can reestablish their coordination with the retinoic acid and sperm production will start again.”

The authors claim that the drug does not damage sperm stem cells or their genomic integrity. As long as the drug was present, the sperm stem cells simply continued to regenerate as stem cells, and when the drug was subsequently removed, the cells could regain their ability to differentiate into mature sperm.

“We weren’t necessarily looking to develop male contraceptives when we discovered SMRT and generated this line of mice, but when we saw that their fertility was disrupted, we were able to follow the science and discover a potential treatment,” explains the first author Suk-Hyun Hong, a researcher in Evans’ lab. “This is a great example of how Salk’s basic biological research can lead to major translational impact.”

More information:

Targeting nuclear receptor corepressors for reversible male contraception, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2024). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2320129121. www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.2320129121

Provided by the Salk Institute

Quote: Scientists discover new target for reversible, non-hormonal male birth control (February 20, 2024) retrieved February 20, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.