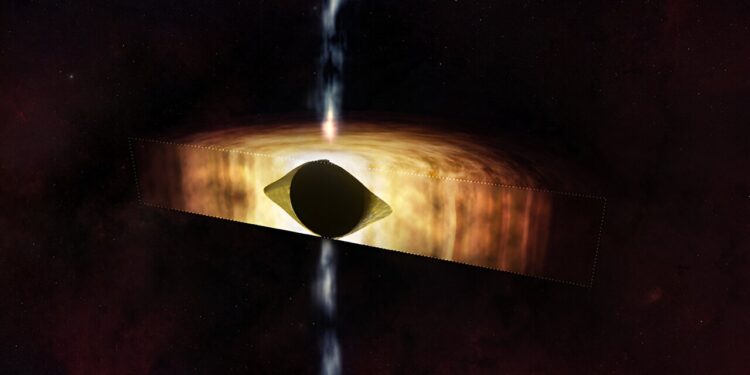

This artist’s illustration depicts the results of a new study of the supermassive black hole at the center of our galaxy called Sagittarius A* (abbreviated Sgr A*). As reported in our last press release, this result revealed that Sgr A* rotates so quickly that it distorts spacetime, that is, time and all three dimensions of space, so that it looks more like a football. Credit: Chandra Radiography Center

The supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way rotates so quickly that it distorts the space-time around it into a shape that can resemble a football, according to a new study using data from the observatory at Chandra X-rays from NASA and National Science. Very Large Karl G. Jansky Network (VLA) Foundation.

Astronomers call this giant black hole Sagittarius A* (Sgr A* for short), located about 26,000 light years from Earth, at the center of our galaxy.

Black holes have two fundamental properties: their mass (its weight) and their rotation (the speed at which they rotate). Determining either of these two values tells scientists a lot about a black hole and its behavior.

A team of researchers applied a new method that uses X-ray and X-ray data to determine the rotation speed of Sgr A* based on how matter flows to and from the black hole. They discovered that Sgr A* rotates with an angular velocity (the number of revolutions per second) that is about 60% of the maximum possible value, a limit set by the material which cannot move faster than the speed of the light.

In the past, different astronomers have made several other estimates of Sgr A*’s rotation speed using different techniques, with results ranging from Sgr A* not rotating at all to near maximum rotation.

“Our work could help resolve the question of how fast our galaxy’s supermassive black hole spins,” said Ruth Daly of Penn State University, lead author of the new study. “Our results indicate that Sgr A* rotates very quickly, which is interesting and has broad implications.”

A spinning black hole attracts “spacetime” (the combination of time and three dimensions of space) and neighboring matter as it spins. The spacetime around the rotating black hole is also crushed. Looking at a black hole from above, along the barrel of any jet it produces, spacetime is a circular shape. However, looking at the rotating black hole from the side, spacetime is shaped like a football. The faster the spin, the flatter the ball.

The rotation of a black hole can be a significant source of energy. Rotating supermassive black holes can produce collimated streams, that is, narrow beams of matter such as jets, when their rotational energy is extracted, which requires that there be at least some matter near the black hole.

Due to limited fuel around Sgr A*, this black hole has been relatively quiet over the past few millennia with relatively weak jets. This work shows, however, that this could change if the amount of material near Sgr A* increases.

“A spinning black hole is like a rocket on the launch pad,” said co-author Biny Sebastian of the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg, Canada. “Once the material gets close enough, it’s like someone fueled the rocket and pressed the ‘launch’ button.”

Chandra X-ray image of Sagittarius A* and surrounding region. Credit: NASA/CXC/Univ. of Wisconsin/Y.Bai, et al.

This means that in the future, if the properties of matter and the strength of the magnetic field near the black hole change, part of the black hole’s enormous rotational energy could generate more powerful outflows. This source material could come from gas or the remains of a star torn apart by the black hole’s gravity if that star moves too far from Sgr A*.

“Jets propelled and collimated by a galaxy’s rotating central black hole can profoundly affect an entire galaxy’s gas supply, affecting how quickly and even whether stars form,” the study said. co-author Megan Donahue of Michigan State University. “The ‘Fermi bubbles’ observed in X-rays and gamma rays around our Milky Way’s black hole show that the black hole was likely active in the past. Measuring the rotation of our black hole is an important test of this scenario .”

To determine the spin of Sgr A*, the authors used an empirical theoretical method called the “flow method” that details the relationship between the spin of the black hole and its mass, the properties of matter near the black hole, and output properties.

The collimated flow produces the radio waves, while the disk of gas surrounding the black hole is responsible for the X-ray emission. Using this method, the researchers combined data from Chandra and the VLA with an independent estimate of the mass of the black hole from other telescopes to limit the rotation of the black hole.

“We have a special view of Sgr A* because it is the closest supermassive black hole to us,” said co-author Anan Lu of McGill University in Montreal, Canada. “While it’s quiet at the moment, our work shows that in the future it will provide an incredibly powerful boost to surrounding matter. This could happen in a thousand or a million years, or it could happen in course of our lives.”

The study is published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

More information:

Ruth A Daly et al, New black hole spin values for Sagittarius A* obtained with the output method, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (2023). DOI: 10.1093/mnras/stad3228

Provided by Chandra X-ray Center

Quote: Telescopes show Milky Way black hole ready for a kick (February 8, 2024) retrieved February 9, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.