Graphical summary. Credit: Cell (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.01.008

A multinational team of researchers led by Columbia University has discovered that tumors can reuse a single cellular protein to hide from the immune system in two distinct ways. Drugs targeting this protein could deliver a double blow against many cancers and make immunotherapy, one of the newest types of anti-tumor therapies, even more effective.

One of the hallmarks of cancer is genome instability, an increased tendency of the genome to acquire mutations during cell division. This genome instability in turn triggers innate immune sensors in the cell, which then recognize fragments of genetic material that escape from the cell nucleus into the surrounding cytoplasm.

“This may be beneficial in the context of cancer treatment, because it can lead to the release of chemokines that attract immune cells into the tumor,” says Alberto Ciccia, associate professor of genetics and development at Columbia and member of the Herbert Irving Comprehensive Cancer. Center. Responding immune cells can then kill the cancer cell before it gets out of control.

Unfortunately, some cancers manage to activate an immune response, essentially a “nothing to see here” signal, to evade the initial response. Newly developed therapies, a type of immunotherapy called checkpoint inhibitors, can overcome this problem by suppressing the checkpoint response, but these immune checkpoint blocking treatments still fail in some patients.

SMARCAL1: a single-molecule immune evasion system

“We wanted to study the interplay between the innate immune response and the immune checkpoint response,” says Ciccia, lead author of the paper describing the new findings, published in the journal Cell. Giuseppe Leuzzi, a postdoctoral researcher in Ciccia’s lab, led the study using a smart genetic screen to identify cellular proteins linked to both responses. “We expected to find factors that could positively regulate both responses,” says Ciccia. However, the team discovered a subset of proteins with opposing effects on the two responses.

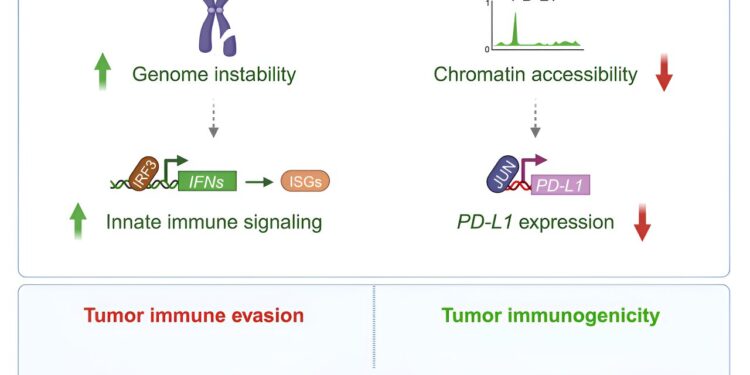

One protein in particular, called SMARCAL1, appears to suppress innate immune signaling while inducing the production of immune checkpoint proteins; it is a single-molecule immune evasion system. “When you inactivate this factor, you activate the innate immune pathway and reduce the expression of one of the immune checkpoint proteins,” Ciccia explains.

Working with an international team of collaborators from several other institutions, the investigators demonstrated that the two functions operate via two distinct mechanisms. SMARCAL1 functions as a factor that maintains genome stability during DNA replication, as well as a transcriptional regulator that can induce the production of immune checkpoint proteins.

A promising target for new therapies

“By targeting this factor, we could achieve a dual benefit, by increasing innate immunity and infiltration of tumors by immune cells, and by limiting the ability of cancer cells to evade the immune system via immune checkpoints” , explains Ciccia. The team tested this idea in a mouse model of tumor immune responses, with promising results. They also analyzed patient data from the Cancer Genome Atlas and found that high SMARCAL1 expression correlated with poor clinical outcomes.

“We hope to be able to develop small-molecule SMARCAL1 inhibitors and see if we can recapitulate the effects we see in our genetic models,” says Ciccia. Although he emphasizes that many obstacles remain in turning new discoveries into effective therapies, Ciccia is optimistic about the prospects. Indeed, SMARCAL1 was not the only potential target identified by the team during the initial selection. “These are factors that, when you turn them off, can allow you to get several different responses that could be beneficial,” Ciccia says.

More information:

Giuseppe Leuzzi et al, SMARCAL1 is a dual regulator of innate immune signaling and PD-L1 expression that promotes tumor immune evasion, Cell (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2024.01.008

Provided by Columbia University Irving Medical Center

Quote: A one-molecule immune evasion system: New discovery could pack a punch against cancer (February 2, 2024) retrieved February 2, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Except for fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.