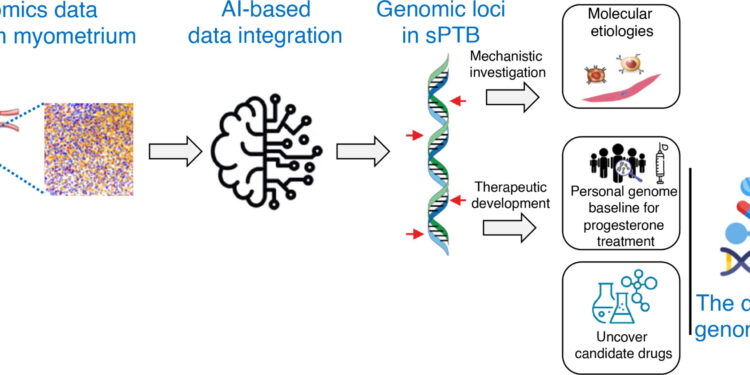

Study design shown in flowchart. Credit: Scientists progress (2024). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adk1057

A UC San Francisco-led study has for the first time identified genetic variants that predict whether patients will respond to treatment for preterm birth, a condition that affects one in 10 infants born in the United States.

The findings are critical because no drugs are available in the United States to treat preterm birth. Last year, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) removed from the market the only treatment approved to help prevent the disease, a synthetic form of progesterone sold under the brand name Makena, citing its ineffectiveness.

The new research found that pregnant people with high levels of mutations in certain genes, particularly those associated with involuntary muscle contraction, were less likely to respond to treatment. Screening for mutations could allow doctors to target the drug to people most likely to benefit, the authors suggest.

“This study requires a precision framework for future drug development,” said the study’s lead author, Jingjing Li, Ph.D., associate professor in the UCSF Department of Neurology and the Eli Center. Edythe of regenerative medicine and stem cell research. “In addition to understanding the effects of medications based on population averages, we also need to consider each patient’s response to medications and ask why some respond and others don’t.”

The study, conducted in collaboration with Stanford University, appears in the journal Scientists progress.

New genes associated with premature birth

Premature birth, or babies born alive before 37 weeks of gestation, is the leading cause of infant mortality and affects some 15 million pregnancies worldwide each year. Premature birth also causes a range of long-term health consequences, including breathing problems, neurological impairments such as cerebral palsy, developmental disabilities, vision and hearing impairments, heart disease and other illnesses. chronicles.

To conduct the study, researchers developed a machine learning framework to analyze the genomes of 43,568 patients who gave birth spontaneously prematurely. The approach revealed genes not previously known to be associated with premature birth.

They then looked at genetic mutations in those who received the Makena progesterone treatment. The FDA approved the drug in 2011 after a single clinical trial, but pulled it from the market last spring after concluding the drug was not effective.

The decision left doctors without an approved drug for premature birth and frustrated those who had found it effective for a subset of their patients. This begged the question: Could there be a genetic reason why progesterone treatment worked for some but not others?

The researchers found that patients in the group with low levels of mutations in genes associated with muscle contractions were more likely to respond to Makena, but those with higher levels tended not to respond.

The finding indicates that a personalized medicine approach involving genetic screening could lead to positive patient outcomes without a high burden of these mutations.

“Progesterone therapy was the only treatment for recurrent preterm birth for the past decade, and its recent withdrawal by the FDA has left a gap in the drug options available for patients giving birth preterm,” said the former. Study author Cheng Wang, Ph.D., a postdoctoral researcher at UCSF.

“In previous clinical practice, we found that many patients benefited from progesterone treatment,” Wang said. “We should probably re-evaluate its effectiveness, if we can identify those who respond positively to treatment.”

The researchers included a cohort of African American patients in the study to determine whether the findings applied broadly to different races. In the United States, black women are almost twice as likely to give birth prematurely as white women.

They found that genetic load did not vary by race. This suggests that the high rate of preterm births among black mothers may be due primarily to environmental factors such as high stress hormones, health care biases, and a lack of prenatal care.

A new type of precision medicine

Researchers then went beyond these findings to identify new targets and potential treatments to treat premature birth. They looked at more than 4,000 compounds and narrowed down 10 that were predicted to interact with genes associated with premature birth.

Many of these therapeutic compounds are already used to treat cancer and other diseases, meaning these drugs could eventually be repurposed to help prevent premature labor.

One of the top candidates is the small molecule RKI-1447, a drug currently used to treat cancer, glaucoma and fatty liver disease. Additional studies on the potential of these molecules in the treatment of premature births are needed.

More information:

Cheng Wang et al, Integrative analysis of non-coding mutations identifies druggable genome in preterm birth, Scientists progress (2024). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adk1057

Provided by University of California, San Francisco

Quote: Genetic discovery reveals who can benefit from treatment for premature births (January 23, 2024) retrieved January 23, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from fair use for private study or research purposes, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for information only.