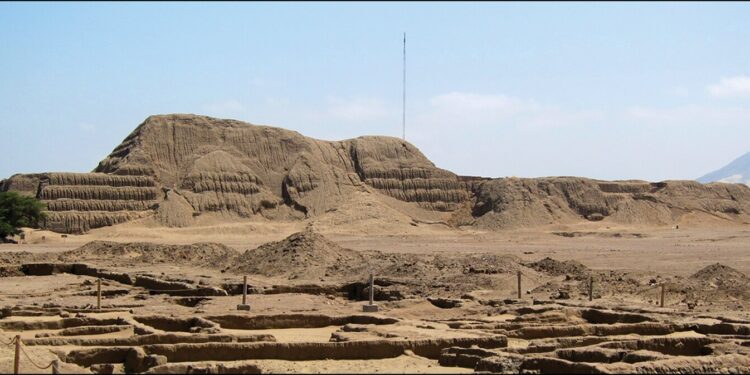

Huaca del Sol with the remains of the urban area in the foreground. Credit: Antiquity (2024). DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2024.138

Archaeologists have analyzed textiles from the ancient city of Huacas de Moche in Peru, showing how the people’s cultural traditions survived in the face of outside influences.

After the Inca culture, the Moche culture is one of the best-known archaeological cultures in the Andes. It is famous for its colorful temple complexes, the largest of which, Huacas del Sol at Huacas de Moche, one of the largest known Moche sites, was perhaps the largest structure in the New World at its peak (c. 650–900 AD).

Despite this, relatively little is known about the causes of the end of the Moche culture. It has often been hypothesized that it was wiped out by the expansion of the powerful Wari empire.

“The people who built the Huacas de Moche, now known as the Moche (aka the Mochicas), are known to us only through archaeology because they had no writing system,” said lead author Dr. Jeffrey Quilter of the Peabody Museum at Harvard University.

“The period in which the Moche culture existed has been a subject of debate for many decades.”

In an attempt to determine the end date of the Moche culture, a team of researchers from several North and South American institutions, including the National University of Trujillo, analyzed and dated the material culture of the Huacas de Moche, focusing particularly on textiles. The work is published in the journal Antiquity.

“Our research has been about tackling the thorny and complex question of how ancient peoples identified themselves,” says Dr. Quilter. “In short, when did the Moche stop being Moche at the Huacas de Moche site?”

By analyzing the production techniques and styles of the textiles, they determined that the majority of them were made using Moche techniques, but often contained design influences from other cultures, including the vast Wari empire of the southern highlands of Peru.

Radiocarbon dating of these textiles revealed that they date to the 10th century A.D., much later than previously estimated. This suggests that the Moche sense of identity may have persisted longer than previously thought. Importantly, these findings highlight the resilience of Moche culture while adapting to foreign influences.

It is not possible, however, to determine with certainty through archaeology whether the people who preserved the old customs and adapted to the new ones considered themselves Mochica.

This challenges the way we think about archaeological cultures. The Moche culture may not have “disappeared” permanently, nor been wiped out by the expansion of a “stronger” neighbor, nor by a climatic phenomenon. Rather, the culture transformed over time as a result of its interactions with different peoples.

(Left) Aerial view of Huaca del Sol annotated with sections 1 to 4 and the excavation units of section 4; right) detail of the level 2 elements in the western part of excavation unit 1. Credit: Authors, Antiquity (2024). DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2024.138

“Our research indicates that long-standing Moche material cultural practices and styles continued to be valued at Huacas de Moche, long after the presumed end of the archaeological culture,” says Dr. Carlos Rengifo of the National University of Trujillo.

“Even though the world around them has changed, some sense of Moche identity seems to have been retained.”

It also highlights the difficulties of examining past cultural identity without written evidence.

“Until recently, it’s likely that no one referred to themselves as Ugly,” Dr Quilter concludes.

“Nevertheless, the archaeological culture we call Moche clearly represents a sociocultural phenomenon and a distinct identity for the peoples who participated in it. Just as it is difficult to determine the cultural identity of any prehistoric community, it is equally difficult to identify how it came to adopt a new one.”

More information:

Jeffrey Quilter et al., Textiles, Dates and Identity in the Late Occupation of the Huacas de Moche, Peru, Antiquity (2024). DOI: 10.15184/aqy.2024.138

Quote:1,000-Year-Old Textiles Reveal Cultural Resilience of Ancient Andes (2024, September 24) Retrieved September 24, 2024 from

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no part may be reproduced without written permission. The content is provided for informational purposes only.